MONTESA COTA 200

The Most Fun You Can Have Going Slow.

CYCLE WORLD TEST

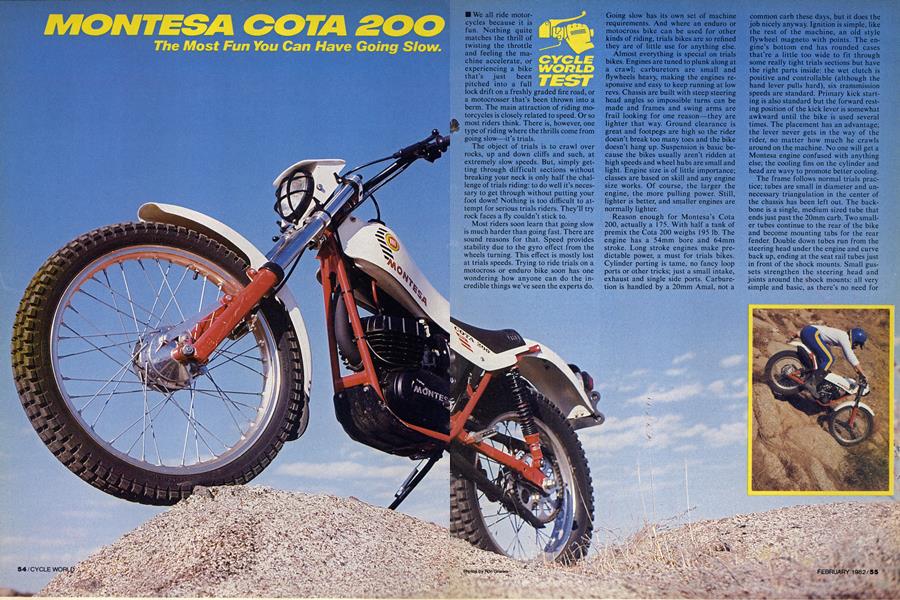

We all ride motorcycles because it is fun. Nothing quite matches the thrill of twisting the throttle and feeling the machine accelerate, or experiencing a bike that’s just been pitched into a full lock drift on a freshly graded fire road, or a motocrosser that’s been thrown into a berm. The main attraction of riding motorcycles is closely related to speed. Or so most riders think. There is, however, one type of riding where the thrills come from going slow—it’s trials.

The object of trials is to crawl over rocks, up and down cliffs and such, at extremely slow speeds. But, simply getting through difficult sections without breaking your neck is only half the challenge of trials riding: to do well it’s necessary to get through without putting your foot down! Nothing is too difficult to attempt for serious trials riders. They’ll try rock faces a fly couldn’t stick to.

Most riders soon learn that going slow is much harder than going fast. There are sound reasons for that. Speed provides stability due to the gyro effect from the wheels turning. This effect is mostly lost at trials speeds. Trying to ride trials on a motocross or enduro bike soon has one wondering how anyone can do the incredible things we’ve seen the experts do. Going slow has its own set of machine requirements. And where an enduro or motocross bike can be used for other kinds of riding, trials bikes are so refined they are of little use for anything else.

Almost everything is special on trials bikes. Engines are tuned to plunk along at a crawl; carburetors are small and flywheels heavy, making the engines responsive and easy to keep running at low revs. Chassis are built with steep steering head angles so impossible turns can be made and frames and swing arms are frail looking for one reason—they are lighter that way. Ground clearance is great and footpegs are high so the rider doesn’t break too many toes and the bike doesn’t hang up. Suspension is basic because the bikes usually aren’t ridden at high speeds and wheel hubs are small and light. Engine size is of little importance; classes are based on skill and any engine size works. Of course, the larger the engine, the more pulling power. Still, lighter is better, and smaller engines are normally lighter.

Reason enough for Montesa’s Cota 200, actually a 175. With half a tank of premix the Cota 200 weighs 195 lb. The engine has a 54mm bore and 64mm stroke. Long stroke engines make predictable power, a must for trials bikes. Cylinder porting is tame, no fancy loop ports or other tricks; just a small intake, exhaust and single side ports. Carburetion is handled by a 20mm Amal, not a common carb these days, but it does the job nicely anyway. Ignition is simple, like the rest of the machine, an old style flywheel magneto with points. The engine’s bottom end has rounded cases that’re a little too wide to fit through some really tight trials sections but have the right parts inside: the wet clutch is positive and controllable (although the hand lever pulls hard), six transmission speeds are standard. Primary kick starting is also standard but the forward resting position of the kick lever is somewhat awkward until the bike is used several times. The placement has an advantage; the lever never gets in the way of the rider, no matter how much he crawls around on the machine. No one will get a Montesa engine confused with anything else; the cooling fins on the cylinder and head are wavy to promote better cooling.

The frame follows normal trials practice; tubes are small in diameter and unnecessary triangulation in the center of the chassis has been left out. The backbone is a single, medium sized tube that ends just past the 20mm carb. Two smaller tubes continue to the rear of the bike and become mounting tabs for the rear fender. Double down tubes run from the steering head under the engine and curve back up, ending at the seat rail tubes just in front of the shock mounts. Small gussets strengthen the steering head and joints around the shock mounts: all very simple and basic, as there’s no need for more strengthening and weight. This simplicity also makes it easy to route the exhaust pipe that contains lots of packing to help the separate silencer mounted at the end of it.

Rear suspension is handled by Betor shocks mounted at an angle to an ovaltube swing arm. The shocks are basic non-gas units that were common to all bikes a few years ago. Spring preload is the only adjustment. Rear wheel travel is a modest 4.5 in. but more isn’t necessary for most trials speeds.

Front suspension is via Montesa-built hydraulic oil/spring forks with 6.7 in. of wheel travel. Stanchion tubes are 35mm in diameter, more than adequate for the designed use. Lower leg castings have the axle boss placed in front of the leg, but at the bottom of it as height isn’t a problem with less than 7 in. of travel.

Frail looking small hubs, spokes, and brakes are adequate for low speeds. Chain adjustment is made by loosening the axle nut and turning snail adjusters. The small 420 chain is fitted with a rubber cover to protect it from mud and grime.

Controls on the Cota are mostly good. The throttle puts the cable next to the bars, turns easily and can be disassembled quickly without tools as the top is held on with a thumb screw. Handlebars are shaped right and control levers are easy to reach. There’s a switch pod placed on the left side of the bars that turns the lights on, selects high or low beam, kills the engine and operates the feeble horn. Rear brake control is via a right side pedal with a saw-toothed top. It’s tucked in out of the way so rocks won’t prune it off. An exposed cable to the rear brake arm provides good feel and it can’t be damaged as easily as a rod or cable in a housing. The left side shift lever is a whopping 9 in. from the center of the footpeg, so the rider can crawl all over the machine without bumping it out of gear, and trials riding usually means you’re in one gear through most traps. The lever end doesn’t fold, but it’s short and we didn’t have many problems with it hanging or snagging on things. Even so, a folding tip would be better.

The little Cota is one of the few motorcycles still using fiberglass for body parts. The seat/tank unit is a fiberglass part that’s well-finished and attractive but one fall in a rock pile could end it all. The unit attaches to the frame with a cross bolt at the front and rubber straps at the rear. Unhooking the rear straps lets the whole thing swing up for access to the tool tray on the frame backbone. The seat is hard and short, normal for trials bikes since they are designed for stand-up riding. The whole unit is nicely made, narrow in the middle and attractive.

When you look at a trials bike you know it’s different from other bikes; sitting on one is further indication of that. The seat feels like it’s on the ground after riding a 38-in.-high motocrosser. The Cota seat is only a little over 30 in. off the ground and the footpegs are placed in the middle of that distance.

Our Cota 200 almost always fired first kick, hot or cold. Warm-up is quick and the bike can be ridden almost as soon as it’s started. No need to use low gear when starting, or even second for that matter, the Cota will pull smartly away in third from a dead stop. Shifting through the six-speeds is a little clumsy until the bike is ridden a few times; shifting requires moving the foot off the peg and lunging forward to the lever. Additionally, the lever doesn’t move easily, but its hard movement is intentional; it won’t get bumped out of gear as easily when you’re trying to scale the side of a rock face or some other impossible looking challenge.

Engine response is amazing. Turning the throttle up at less than a walking speed results in instant forward movement, and the power surge is completely controllable and predictable. The engine never stalls or hesitates or burps. The Cota’s six-speed transmission has widely spaced ratios so the rider has a tremendous choice for any situation. First is extremely low at 47.57:1, and sixth is high at 10.41 to one. Second figures out at 38.37:1 and the rest of the ratios are fairly well distributed between second and sixth. Thus, cruising to a section via a double track road doesn’t pose any problem for the little engine. It will purr right along at 50 or so.

Standing on the pegs, negotiating a tight, tricky section is where the Cota 200 shines; the steep (26.5°) steering head angle and generous steering lock make impossible turns easy. And the brakes that are not enough on the road are per> feet in a trials section; they’re strong enough to allow adequate braking without fear of locking the wheels and the subsequent front end slide or engine flameout.

MONTESA

COTA 200

$2089

The tame engine with its heavy flywheel and good gear ratios make one feel like Spyder Man. After a few hours on the Cota the rider might try anything— and probably make it. The 200 does almost everything better than a larger trials bike except for raising the front wheel by blipping the throttle. The Cota takes more throttle and more effort on the part of the rider.

The Cota 200 sells for $2089. That's a lot of money for a 200 anything, but trials bikes don’t change radically from year to year as do other types of motorcycles. So, three years down the road, the new '85 Cota may very well look the same. And trials bikes don't get tortured like motocross and enduro bikes, so they usually last much longer. The Cota 200 offers good value for the money as long as you don't get too picky about some of the smaller things. Almost all of the rubber parts were already cracking, and the cracking intake manifold caused concern. Replacing it with a radiator hose, a common replacement material for rubber manifolds, won't be easy because the two ends are different sizes. Even so, it's a small price to pay for endless fun. B3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

FEBRUARY 1982 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

FEBRUARY 1982 -

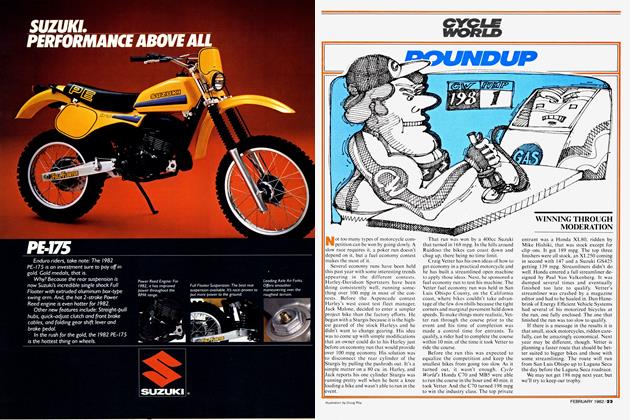

Cycle World

Cycle WorldRoundup

FEBRUARY 1982 -

Features

FeaturesRiding the Winner

FEBRUARY 1982 By John Ulrich -

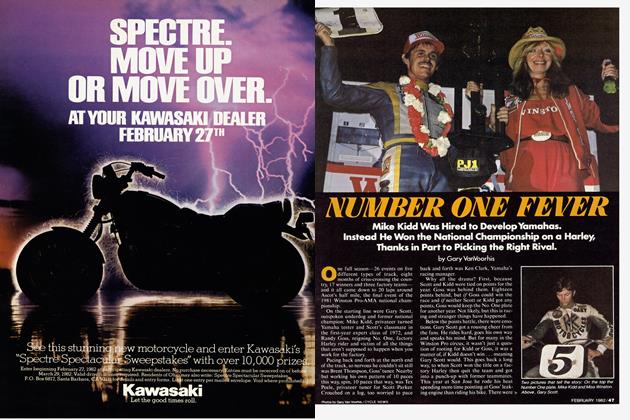

Competition

CompetitionNumber One Fever

FEBRUARY 1982 By Gary Vanvoorhis -

Race Watch

Race WatchWills Sets Record, Collins Wins At Ocir

FEBRUARY 1982 By Joel Breault