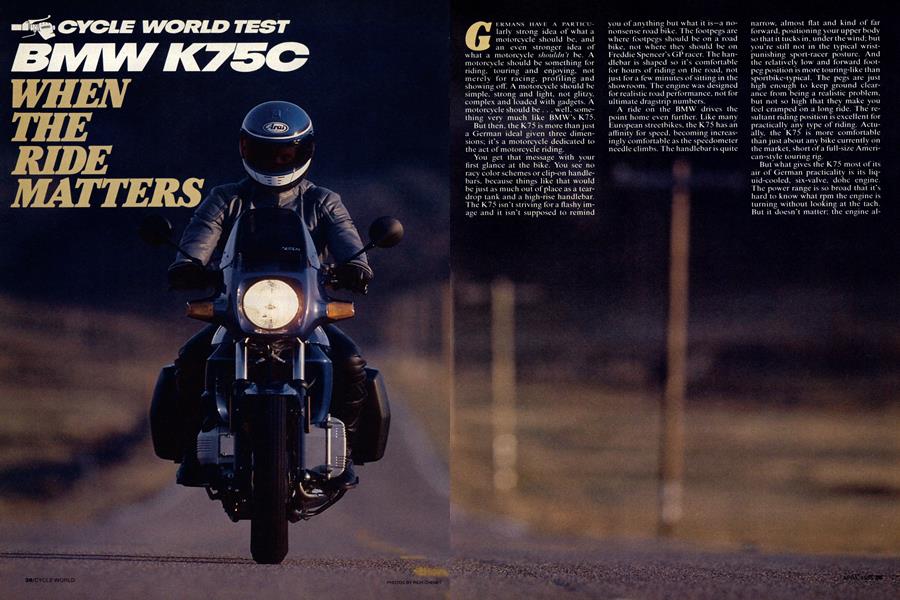

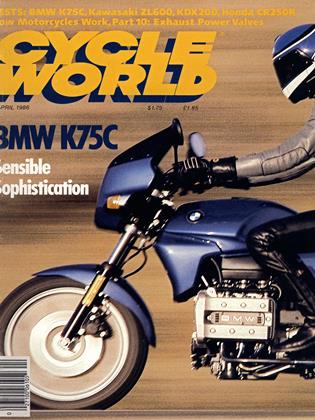

BMW K75C

CYCLE WORLD TEST

WHEN THE RIDE MATTERS

GERMANS HAVE A PARTICUlarly strong idea of what a motorcycle should be, and an even stronger idea of what a motorcycle shouldn't be. A motorcycle should be something for riding, touring and enjoying, not merely for racing, profiling and showing off. A motorcycle should be simple, strong and light, not glitzy, complex and loaded with gadgets. À motorcycle should be . . . well, something very much like BMW’s K75.

But then, the K7~ is more than Just a German ideal given three dimen sions; it's a motorcycle dedicated to the act of niotorcycle riding.

You get that message with your first glance at the hike. YOU SCC 110 racy color schemes or clip-on handle bars, because things like that would he just as much out of place as a teardrop tank and a high-rise handlebar. i'he K75 isn't striving for a flashy im age and it isn't supposed to remind

ou of any thing hut what it is-a nononsense road hike. the ftotpegs are where footpegs should he on a road hike, not where they should he on Freddie Spencer's (iP racer. the han dlebar is shaped so it's comfortable for hours of riding on the road, not just for a f~w minutes olsitting in the showroom. Uhe engine was designed for realistic road performance. not for ultimate dragstrip numbers.

A ride on the 13MW drives the point home even f'urther. Like many luropean streethikes. the K75 has an allinity for speed. becoming increas ingly comfortable as the speedometer needle climbs. Ihe handlebar is quite

narrow. almost hat and kind ol (hr forward, positioning your upper body so that it tucks in. tinder the wind~ hut youre still not ifl the typical wristpunishing sport-racer posture. And the relatively low and f~rward l~otpeg position is more touring-like than sporthike-typical. The pegs are just high enough to keep ground clear ance from being a realistic problem. but not so high that they make you t~el cramped on a long ride. l'he resultan t riding position is excellent f~r practically any type of riding. Actu ally. the K 75 is more conif~rtahle than Just about any hike currently on the market, short ota lii I I-size Amencan-style touring rig.

Rut what gives the K75 most ol its air of (ierman practicality is its liq uid-cooled, six-valve, dohc engine. The power range is so broad that it's hard to know what rpm the engine is turning without looking at the tach. Rut it doesn't matter~ the engine always seems to pull, regardless. When going through a turn, you can shift now, you can shift later, or you don't have to shift at all. The K75 has a torque curve that is as broad as that of most literbikes.

This 750cc BMW won't set any speed records, though, not with its claimed 75 horses. But it's BMW's philosophy that a motorcycle doesn't have to produce enough power to spin the earth on its axis, that a bike should have only as much power as it needs-no more, no less. And that's precisely what the K75 has.

That same kind of Teutonic logic seemed to dictate the way the rest of the bike was built, too. BMW did just what was necessary to produce the 750, without waste, without extrava gance. The engine is, for all intents and purposes, a four-cylinder, 98 7cc K 100 engine with one cylinder-and its 247cc of displacement-lopped off the front. The result is a 740cc Triple.

Some might call that cheap and easy engineering, not logical and functional; but this simply isn't the case, because both the three-cylinder K75 and the four-cylinder K100

were designed and developed simul taneously. BMW was, after all, al ready making one radical move by departing from the traditional boxer Twin. To expect dealers and custom ers to have a positive reaction to two completely new and different designs would not have been realistic. Be sides, BMW claims that 80 percent of the K75's parts are interchangeable with the latest Kl 00's. That is logical and functional.

Which is not to say that there are no differences between the two mo torcycles other than cylinder count.

For one, the K75 uses a gear-driven counterbalancer running parallel to the crankshaft. It smoothes the vibra tions that arise due to the the rockingcouple produced by the K75's threethrow, 120-degree crankshaft. The K75 also makes more horsepower per cubic centimeter than its KI00 big brother, a feat accomplished through a higher compression ratio (11: 1 on the K75, compared with 10.2:1 on the K 100), redesigned combustion chambers, shorter intake manifolds and different exhaust-system tuning.

Other technical aspe~ts of the K75

are common with the Kl00. Both have Bosch electronic fuel injection, and both engines drive through a dry clutch, a five-speed transmission and a shaft final drive. The K75's finaldrive ratio is slightly lower (higher numerically) than the K 100's, but the rear end of the motorcycle has the same unique swingarm arrangement as the Kl00. A single shock, sans linkage, mounts only to one side of the swingarm, simply because there is only one side of the swingarm. The massive, cast-aluminum driveshaft housing is the only structural mem

ber connecting the rear wheel to the motorcycle. This arrangement is very strong, and it makes rear-wheel re moval ridiculously easy.

11 i~.J V (1 & I I `&1~ %.41'.J LA~IJ (4~J. With the K75 having so much in common with the K 100, BMW felt it was important to add a few touches here and there that would give the 750 its own identity. Most are sub tle-such as the shape of the 3-into-i exhaust system's muffler, which is tri angular on the Triple rather than square as on the Four. The K75 has a narrower radiator, as well, which makes the whole bike seem thinner

than the K100. And there also is a small, fork-mounted fairing that will appear only on the K75C model. The touring-oriented K75T comes with a taller windscreen, and the sporty K75S, to be announced later in the year, will have a frame-mounted fair ing. None of the three fairings was lifted from the Kl00, but instead were designed to give the Triple a look all its own.

Still, the K75 could easily pass for a K 100 in the eyes of anyone who isn't paying much attention. But if you ride both bikes, there's no danger of confusing the two. The K75 has the unique exhaust drone produced only by a I 20-degree Triple, whereas the KlOO sounds like a typical four cylinder UJM. And unlike the K 100, the K75 is dead-smooth. At low revs, high revs and everything between, the Triple glides along so smoothly that it could just be coasting downhill with the key turned off. There's no

hint of the left-footpeg vibration that loosened the toenails of most early Kl0O riders. In fact, the K75 will hold its own against any bike when it comes to engine smoothness. The only time the rider is aware of any vibration at all is on trailing throttle, when the engine reminds him of its presence with a very light, low-fre quency buzzing. If you're still not sure which is the

1000 and which is the 750, any twisty road can show you the light. Even though the weight difference is only around 20 pounds, the Triple feels much smaller and lighter. It still isn't what you would call exceptionally light-handling, but only because Ja pan's featherweight Fours with their 16-inch front wheels have set new standards of agility. In true German fashion, however, the K75 steers quickly enough to get the job done, no matter how tight the road.

Working into a smooth and easy rhythm on a snaky road is no problem for the BMW. Cornering is natural and easy, thanks to the bike's omni present power, neutral steering and the sticky Pirelli Phantom tires that came on our test bike (K75s will also be delivered with Continentals, Met zelers and Michelins). And perhaps the biggest contributor to the K75's cooperative handling is the excep tionally low center of gravity pro vided by the laid-down engine.

But the harder the pace. the easier it is to find the BMW's handling lim its. While the twin front disc brakes are fine around town, they just aren't up to super-hard charges on back roads. When you dive into a turn a little too deep, a oneor two-finger squeeze won't cut it; instead, the front brake wants your whole hand on the lever. Then, once your knuck les have turned sufficiently white to slow the Beemer down, fork dive is the next annoyance, for the front end is too soft for serious cut-and-thrust sportbiking antics. The rear suspen sion is a better compromise between freeway and back-route travel. The springing and damping strike an ex cellent balance to create a ride that's always smooth and predictable.

But all is not perfect at the rear end, either, for it is there, in the shaft final drive, where you will find the K75C's single most annoying trait: torque reaction by the chassis, a characteristic that has almost become a BMW trademark. Practically every time you upshift or open the throttle very quickly, the entire bike raises up on its suspension; snapping the throt tle closed causes the bike to squat down on its fork and shock. A sud den blip of the gas can cause the bike to jump up so violently that it feels like the rear wheel has come off'~he ground. This chassis behavior, long time Beemerphiles will say, is some thing you can get used to. But in this day and age of motorcycle sophistica tion, you shouldn't have to "get used to" anything.

But then, K75 owners won't have to get used to the cramped riding po sitions, the bothersome engine vibra tions, the all-or-nothing powerbands and the overall impracticality preva lent in so many modern motorcycles. That's a more-than-fair trade-off, es pecially in view of the K75C's list price of $4700. For that, you get a very German motorcycle at a very Japanese price. You don't get much in the way of frills or exotic images, only what's necessary for the ride. That's the German way. And after

a ride on a K75, you just might be lieve that it's the right way.

BMW K75C

SPECIFICATIONS

$4700

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialBack To Square One?

April 1986 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeThe Ultimate Vee

April 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupLatest Ninja Offspring

April 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupThe Black Queen

April 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

Features

FeaturesHigh In the Thin, Cold Air

April 1986 By Koji Hiroe