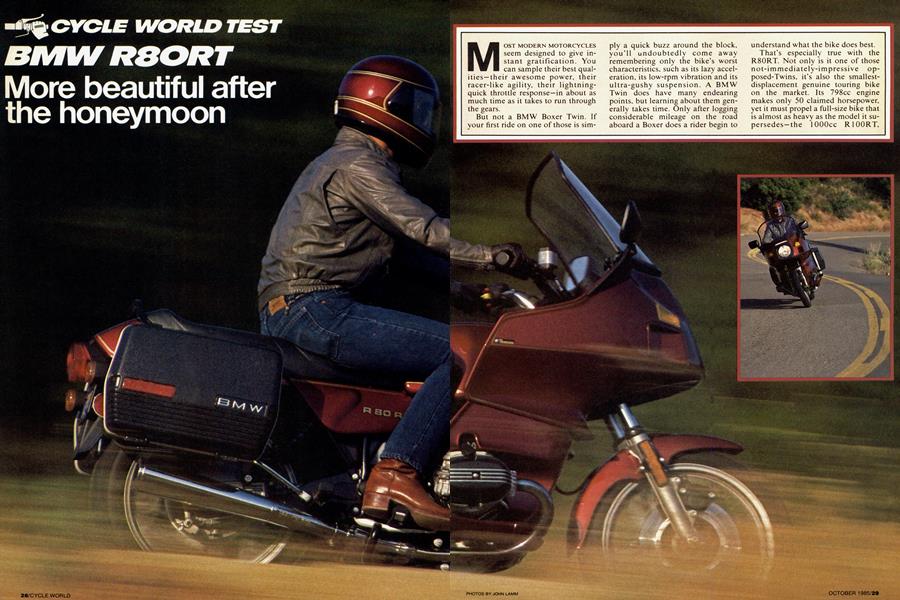

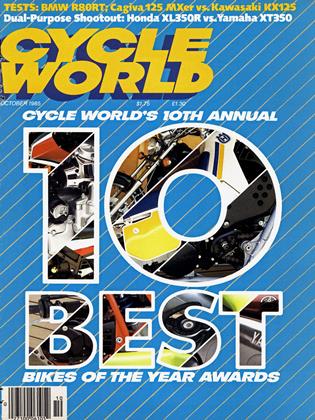

BMW R80RT

CYCLE WORLD TEST

More beautiful after the honeymoon

MOST MODERN MOTORCYCLES seem designed to give instant gratification. You can sample their best qualities—their awesome power, their racer-like agility, their lightningquick throttle response—in about as much time as it takes to run through the gears.

But not a BMW Boxer Twin. If your first ride on one of those is simply a quick buzz around the block, you’ll undoubtedly come away remembering only the bike’s worst characteristics, such as its lazy acceleration, its low-rpm vibration and its ultra-gushy suspension. A BMW Twin does have many endearing points, but learning about them generally takes time. Only after logging considerable mileage on the road aboard a Boxer does a rider begin to understand what the bike does best.

That’s especially true with the R80RT. Not only is it one of those not-immediately-impressive opposed-Twins, it’s also the smallestdisplacement genuine touring bike on the market. Its 798cc engine makes only 50 claimed horsepower, yet it must propel a full-size bike that is almost as heavy as the model it supersedes—the lOOOcc R100RT, which itself was no ball of high-performance fire. So, the R80RT isn’t going to knock anyone’s socks off during a spin around the block.

On the other hand, this BMW has no competition. There is no other fully faired bike in the R80RT's price range or displacement category, so it fills a small niche in the market. It's a lower-priced, lighter-weight, mid-displacement alternative to the big touring rigs. The RT is devoid of all the gadgets that are standard on the Japanese-built tour bikes, but at $5700, it’s also a couple of grand cheaper.

Mechanically, the R80RT is an interesting mix of old and new. Its overhead-valve engine is of the same basic design that has been powering BMWs for more than half a century, while its chassis is built around the latest version of the company’s unique Monolever single-shock rear suspension first used on the R80 G/S dual-purpose bike a few years ago. Much of the R80RT's bodywork has new shapes and contours, but the full-coverage touring fairing is the same as the one used on the R 1 OORT.

There's not much different in the R80RT’s engine, aside from new rocker-arm bearings designed to reduce valve-train noise. Our test bike seemed no quieter than previous BMWs we have ridden, however, so the effect of this refinement apparently is minimal. Same goes for the bike’s new exhaust system. It’s still a 2-into-2 arrangement, but with the crossover pipe now welded to the header pipes rather than bolted to them. BMW claims this makes the system 3 decibels quieter than its predecessor, while allowing slightly better engine performance and improved fuel economy. But again, our seat-of-the-pants dynos couldn't sense the difference.

Power-wise, the RT is typical BMW fare, in quality if not in quantity. The delivery is almost perfectly linear between idle and the 7400rpm redline, with no flat spots anywhere. There’s also no rush of acceleration anywhere, just a moderate, steady increase in speed. Really, though, in light of its heavy flywheels and meager power output, and the fact that the RT weighs just under 500 pounds and has a fairly large frontal area, the R80 couldn’t be expected to be a standout performer.

To help compensate for the RT’s high weight-to-power ratio, BMW gave the bike 1 5-percent lower finaldrive gearing than the R1 OORT’s. That has, no doubt, done good things for acceleration, but it limits top speed to only about 100 mph. And while a touring bike doesn’t really need to go any faster than that, this gearing causes the engine to turn about 4000 rpm at 60 mph. As a result, the nice, low-pitched engine hummmmm that can make open-road traveling on a BMW so soothing is not quite as low-pitched—and thus not as soothing. The R80RT’s engine is still pleasant out on the highway, but it seems to be in much more of a hurry than the R 100's ever was.

Also, because the R80 motor uses the same gearbox as the R100, that low final-drive gearing has moved the overall gear ratios quite a bit closer together. Fourth and fifth in particular now are so close that they don’t make best use of the engine’s wide powerband and decent mid-range torque. But at least the R80 changes gears more easily and quietly than BMWs of years past, although shifting still is a notchier, higher-effort activity than on most Japanese bikes.

On the positive side, that lower gearing does help the engine get up out of its vibration zone more quickly. When accelerating at lower revs, especially below 3000 rpm in the taller gears, the opposed-Twin engine causes the entire bike to shudder, sometimes so badly that you can’t make out a thing in the fairingmounted mirrors. But the engine smoothes out nicely by 4000 rpm, which makes cruising even at 55 mph virtually vibration-free.

Just as the engine is happier at higher speed, so, too, is the R80RT’s chassis. Around town and during stop-and-go riding, the bike feels like a big, American luxury car with bagged-out shock absorbers. The front end dives radically during braking, and the whole chassis rises and falls dramatically as the throttle is rolled open and closed. There’s not much you can easily do to change that behavior, either. The front fork has larger stanchion tubes this year and an integrated fork brace that minimizes front-end flex; but typical of BMWs, the fork is softly sprung and damped, and there are no provisions for any sort of adjustment. And the gas-charged Monolever rear shock—which attaches to the rearaxle housing as on the new K100 series rather than to the single-sided swingarm like on previous R80s—has only four spring-preload positions.

Out on tour, however, particularly over bumpy country roads and secondary routes, the R80’s suspension defines the word “plush.” The more you ride the BMW in that kind of environment, the more you appreciate the way it soaks up all sorts of road irregularities without ever feeling the least bit harsh, despite the rather hard seat. But that’s just one way in which the R80RT grows on you as you spend time on it.

Another is in its handling, which is better-suited to travel on the backroads than it is to cruising the interstates. Actually, the R80 deals with the latter quite well; it’s just that riders conditioned to traveling on mobile entertainment centers are likely to find the BMW dead-boring on the open road, for it has none of the gadgetry that has made the Japanese-built touring rigs so popular.

But a ride through the mountains or on a long, winding country road is a different story. There, the R80RT is a sheer delight, for its comparatively light weight (about 300 pounds less than most American-style touring bikes), along with the exceptionally low center of gravity provided by the opposed-Twin engine, makes it the easiest-handling pure touring bike on the market. Because the single-shock R80RT is about 25 pounds lighter than the twin-shock R100RT, it’s even more agile than its lOOOcc predecessor. It can be flicked over into a corner quickly and easily, even during hard braking, and it allows a rider to move along a twisty piece of road at a spirited but controlled pace. It’s easy to develop a nice, fluid, oneor two-gear backroad rhythm that is exhilarating yet non-tiring.

If you get too aggressive, though, the R80RT immediately lets you know that it’s not a sportbike. A lot of engine-revving and gear-changing result in additional noise but not much else; the opposed-Twin simply doesn’t have enough power to play sport racer. And even though the R80 seems to have a tad more cornering clearance than the twin-shock R100, the chassis responds to kneedragging antics by gouging hardware into the pavement (especially if the throttle is snapped shut in mid-corner) and giving off a rear-end wallow that is just ferocious enough to discourage further aggressiveness.

The main culprit in that wallow seems to be the rear shock, which has insufficient rebound damping to deal with the rigors of full-blitz cornering. But it’s hard to criticize the shock in light of the bike’s touring mission—as well as the superb job the shock does of smoothing out even the most absurdly bumpy roads. It’s one reason why the R80RT delivers its rider at his destination feeling less fatigued than he would on other motorcycles.

Another of those reasons is the R80RT’s full fairing, which offers rider-protection that is exemplary. You can ride the RT in a rainstorm and, if you’re wearing a helmet and you keep moving faster than 30 or 40 mph, never get wet. In hot weather, though, the fairing is almost too protective; and the two little adjustable vents that flank the headlight don’t pass enough air to make things any cooler for the rider.

Some riders will find a few aspects of the windshield displeasing, as well. For one thing, the view through the Plexiglas shield is extremely distorted; and for another, the shield is not tall enough to deflect the air over the helmet of a rider who is more than about 5-feet-9 in height. Whether or not those factors are bothersome depends upon the rider; some are willing to look through the shield just to be fully protected, while others don’t mind enduring a bit of helmet-level buffeting so they can have an unobstructed view over the shield. The latter group won’t mind the R80RT’s shield, but the former will undoubtedly hate it.

And if all R80RTs are like our test unit, just about everybody will despise the brakes. The rear brake is the same drum-type stopper BMWs have used over the last few years, while the twin-disc front brakes have new, larger-diameter rotors for ’85; and the two systems work together to stop the bike quickly, predictably and easily. But in the process, both brakes give off enough squealing and howling to make every stop sound like a thousand fingernails scraping across the world’s biggest blackboard.

It’s also unlikely that anyone will grow fond of the RT’s sidestand, which is the same type of stand that has had BMW riders cursing for more than a decade. Not only is the stand extremely difficult to deploy while you’re sitting on the seat, but it is spring-loaded to retract the instant most of the bike’s weight is taken off of it. The company contends that this design is meant to keep anyone from riding off with the stand deployed, but there has to be a better solution. The centerstand has been redesigned to make getting the bike up on it much easier, but the sidestand still is a very expensive tip-over waiting for a chance to happen.

It’s also difficult to understand the rationale behind certain aspects of the RT’s detachable saddlebags. They do go on and off more quickly and easily than any other bags on the market, but they rattle loudly on their bracketry when empty or lightly loaded; they are so flimsy in construction that they distort when full and require some finagling to get closed; and they aren’t particularly well-made. The bags get the job done, but they don’t say “quality” the way so much of the rest of the bike does.

Nevertheless, despite all its numerous minor faults and major irritations, the R80RT is a competent, likable touring machine. And not just because it is the only touring machine in its size and price category. The RT could be the answer for riders who want just a hint of sport in their longdistance riding, who look on a road map for the little black squiggly lines that lead them to their destinations instead of straight, red ones.

The only catch is that, as with most motorcycles, it’s almost impossible to know if you like the bike until you first know what it does. And on the R80RT, that takes time. 0

BMW

R80RT

$5700

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe Ties That Bind Usually

October 1985 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeFighting Back

October 1985 By Steve Thompson -

Letters

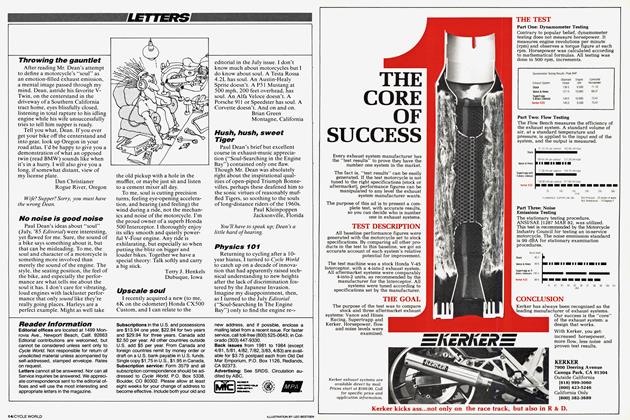

LettersLetters

October 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupForecasting Another Good Year

October 1985 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

October 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

October 1985 By Alan Cathcart