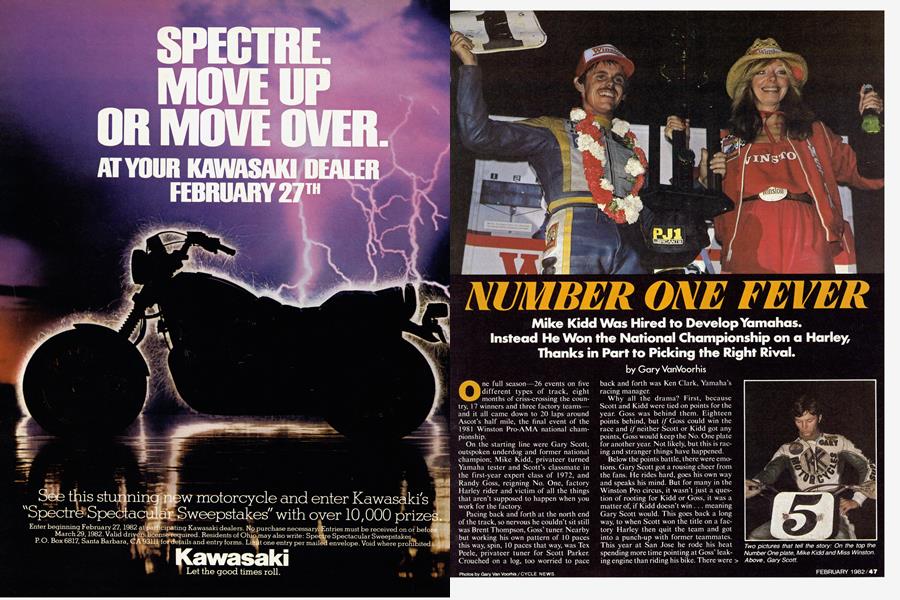

NUMBER ONE FEVER

Mike Kidd Was Hired to Develop Yamahas. Instead He Won the National Championship on a Harley, Thanks in Part to Picking the Right Rival.

Gary VanVoorhis

One full season—26 events on five different types of track, eight months of criss-crossing the country, 17 winners and three factory teams— and it all came down to 20 laps around Ascot’s half mile, the final event of the 1981 Winston Pro-AMA national championship.

On the starting line were Gary Scott, outspoken underdog and former national champion; Mike Kidd, privateer turned Yamaha tester and Scott’s classmate in the first-year expert class of 1972, and Randy Goss, reigning No. One, factory Harley rider and victim of all the things that aren’t supposed to happen when you work for the factory.

Pacing back and forth at the north end of the track, so nervous he couldn’t sit still was Brent Thompson, Goss’ tuner. Nearby but working his own pattern of 10 paces this way, spin, 10 paces that way, was Tex Peele, privateer tuner for Scott Parker. Crouched on a log, too worried to pace back and forth was Ken Clark, Yamaha’s racing manager.

Why all the drama? First, because Scott and Kidd were tied on points for the year. Goss was behind them. Eighteen points behind, but if Goss could win the race and if neither Scott or Kidd got any points, Goss would keep the No. One plate for another year. Not likely, but this is racing and stranger things have happened.

Below the points battle, there were emotions. Gary Scott got a rousing cheer from the fans. He rides hard, goes his own way and speaks his mind. But for many in the Winston Pro circus, it wasn’t just a question of rooting for Kidd or Goss, it was a matter of, if Kidd doesn’t win . . . meaning Gary Scott would. This goes back a long way, to when Scott won the title on a factory Harley then quit the team and got into a punch-up with former teammates. This year at San Jose he rode his heat spending more time pointing at Goss’ leaking engine than riding his bike. There were > nearly blows over that, too.

The atmosphere is best described by saying that after Ascot’s heat races two ostensible rivals approached Mert Lawwill, Kidd's tuner/team manager: would he like to borrow a nice, fresh engine? The offers were declined with thanks but when Bill Werner, H-D tuner for Jay Springsteen, came by with a spare tire he figured would give just a little extra bite, the tire went on Kidd's Harley. (More on that later.)

The actual last race was more like just a race. It was close and furious and fast, but because a second-lap tangle put two riders out, the worst Kidd or Scott could do was finish 12th. That pays three points and that meant Goss’ best would still leave him one point out of the championship.

Goss was the most relaxed rider and worked his way out of the pack and outbraved Terry Poovey for the lead. Kidd meanwhile, spirits boosted by his new tire, blasted away from Scott. He couldn't catch Goss, who always seems to make the tricky Ascot surface work for him, but he did get Poovey. Scott didn't. At the checkered flag it was Goss, Kidd, Poovey and Scott and for the year it was Kidd, Scott and Goss.

“I couldn’t make the low line work in any corner,” Scott said days later. “When 1 saw how well Mike was making his low line work, I knew things were going to be tough. That was the edge, plain and simple. All I could do was ride up high, watch him and hope he made a mistake.”

Did the softer tire from Werner help?

“Perhaps in his mind. But not on the track.”

Kidd meanwhile said he felt sure a large part of the edge he had on Scott was due to the tire.

Scott was gracious in defeat. He appeared in the winner's circle and congratulated Kidd. Goss was even more so. Goss handed Kidd his garland of flowers and the bottle of champagne, telling Kidd it was his night and he should be the one in the limelight. Goss even went as far as to pull a No. One plate from his bike and pass it on to Kidd.

You couldn’t ask for a better season. Four of the 17 winners were first-timers and leading the pack was the irrepressible Jimmy Filice, who looks more like he belongs on a grade school playground than on a fire breathing 750cc dirt tracker. Filice won his first National by out-riding Hank Scott at Louisville. He went on to take Rookie of the Year honors.

Last year’s top rookie Nick Richichi collected his first National win. Richichi, a road racer, was the Loudon winner.

Freddie Spencer gave Team Honda their first Formula One victory at Elkhart Lake and then came back to also win at Pocono. Randy Mamola, Suzuki’s American GP contender, came back for his annual race at Laguna Seca and came away the winner.

Both Hank Scott and Jay Springsteen had three National wins in 1981. Springsteen increased his career total to 28 National wins, tieing him with Bart Markel for second on the all time win list, just one shy of Kenny Roberts’ 29.

In past seasons consistency has been the byword to winning the title. There were seasons recently, most notably Springsteen and Steve Eklund’s title chase in 1978, where if a rider didn’t score WPS points in at least all but two Nationals he could forget it. Not so this year.

Kidd won the title and yet he finished out of the points in eight of 25 Nationals. He combined dirt track with road racing to get as many opportunities to score as possible and ended up with the big zip in just under a third of the races. That’s a helluva comment on the season.

Gary Scott was the most consistent. He got his no point rides out of the way at the start of the season. He scored points in only one of his first four Nationals. From there on Scott was plugging away with the nickle and dime strategy of be there, be there, be there.

The strong suit for any Harley-Davidson factory rider is that he knows that his machinery will finish the race—even if he doesn't. However, a strange thing happened to Goss’ title defense. It started skipping a beat here and there, to the tune of six skipped beats. In a season where if you only ride dirt track you only have 21 chances to score points that is not the way to retain your title.

Statistically it was a rather strange year. Only 84 points separated Kidd from 10th place Steve Morehead. That’s the lowest point spread since the inception of the new (points on a sliding scale of 20, 16, 13, 11, 10 and so on) scoring system in 1976. Every rider in the top 10 won at least one National.

Mike Kidd was fifth in the final 1980 WPS standings. It was the highest he had been in the point standings and he had also finished there in 1979 and 1974. Kidd found himself without a ride because the Army, who had been his sponsor for 197980, was pulling out. Then Kidd hearth about the Kenny Roberts-Mert Lawwill effort to transform the Yamaha Virago 750 V-Twin into a dirt tracker. He was drawn to it like a magnet and his sales pitch was convincing enough so that he and Jimmy Filice became the riders.

The project was basically one of research and development. On paper it was impressive: three former National ChampionsKenny Roberts, Mert Lawwill and Dick Mann—combine forces to build a new dirt tracker from the ground up. In reality, it was a lot to ask in a short period of time.

Given what the elTort was supposed to be, nobody gave Kidd a serious chance at the title. Perhaps a spoiler, but not a contender. Kidd was to be a feed-back rider. That was his job and he was smart enough to know' where the money was coming from. Had the Yamaha come along quicker, the outcome this year might have been different.

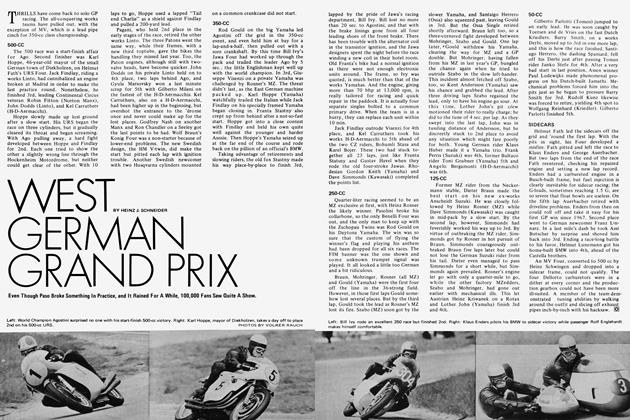

The story behind the Yamaha’s development shows just how close and demanding flat track racing is. The team built a widebased tube frame that straddled the top half of the engine and used the engine as a stressed member, just as the Yamaha factory does for the Virago and XV920. The new bike didn’t handle right. They thought they’d found the problem so they built another frame, same design, different dimensions. That didn’t work either. So they went to a full cradle frame, again making adjustments to engine height, weight distribution, swing arm pivot location and all the countless tiny fractions that matter. Before the San Jose Mile the team was so sure they’d found the problem they thought they could have stayed with the straddle frame after all. Probably have the Yamaha ready for Ascot, they said, only to find that something still wasn't right. Kidd rode the Harley at San Jose and at Ascot while Filice, who had no chance at the title and is the junior member of the team and at age 1 8 has time the 28-year-old Kidd doesn't have, kept on wrestling the lone Yamaha into the Trophy Races.

Kidd’s road racing program was at least as much trouble as the Yamaha tracker. He’s road raced before, back home in Texas before he made expert. But he'd never raced the big bikes and he sold a TZ750 soon after he bought it because he couldn’t get the hang of it. AMA racing includes five road events, though, so a rider out for the championship can't afford to pass it up, especially when Scott can't afford another machine, Goss and Springsteen ride for a factory that doesn't build road racers, etc. It didn’t work. He crashed in practice at Daytona. The throttle jammed and he crashed again at Louden. Roberts gave Kidd a cram course in pavement, and Kidd managed to get through the Laguna Seca National looking only slow.

In something of a contrast, considering their contrast in resources, Scott's campaign proves that a well organized and well executed racing program can pay off and be competitive. Scott didn’t begin 1981 with No. One in mind. He set out to have the best year he possibly could within the financial parameters he had set out for himself.

“I had more fun this year than Fve had in the last three or four seasons,” said Scott. “Those final Nationals were really exciting for me. Donna was along and everybody was working together to pull this thing off. I regret not winning, but it won’t discourage me. If anything I'll be stronger next year.”

Gary and Hank Scott are a classic case of sibling rivalry/cooperation. Their feuds are legendary. Gary is better organized and Hank is better on the miles. When Gary found himself within reach of the championship, he realized at nearly the same time that his miler wasn't working right. Hank offered to swap bikes but Gary figured his machines weren’t that far off. So at Syracuse and San Jose Gary was 1 1th and 8th. Hank finished second both times.

Should Gary have accepted Hank’s offer?

“Looking back, I know I should have. That mistake probably cost me the title.”

What about Hank? In 1980 he was the rider on the line at Ascot and lost the title to Goss by one point. For the final race of 1981 Gary rode Hank's Harley and Hank rode Gary’s. Into the hospital. During time trials he went down hard and the bike hit him, breaking a leg, his pelvis and a collarbone.

After the crash Hank said he was going to retire and go into the engine building business. But a week later he said maybe he’d been premature and that his schedule now calls for him to be back racing in time for the Sacramento Mile in April.

When you’re the champ, you don’t make excuses. Randy Goss learned the hard way that when you're on top the most likely place to go is down. Mechanical problems at crucial times in the season cost Goss a chance to retain his title. At the beginning of the season Goss had to be rated as a favorite to be champ again. After all, he had the Harley-Davidson factory behind him.

Engine failures are basically unheard of in the factory bikes, but Goss had his share. The reason given by Goss was that they were just trying to get too much horsepower from the engine and were doing in pistons. Then there was a crash in the Tulsa National which made Goss a spectator for the day.

It was a season of spurts for Goss. He scored only 14 points in the first five Nationals. Then he reeled off five top five finishes, including a win. Then it was back to famine for two Nationals before another string of four top four finishes.

The final blow came in the double miles at Indy and the single mile events at Syracuse and San Jose. Goss had a sixth and a ninth in four rides.

At Ascot, where Goss also won the spring running of the half mile, he closed out the season in true championship style with the win.

Scott Pearson has been coming on stronger each season. This year he was fifth overall, his best to date, and he collected two wins. He's been overlooked by many, not because he doesn't have the talent but because his machines have been inconsistent.

This was Pearson's fifth season and he has been steadily honing his talents he is one of the few on the dirt who, with good machinery, does not have a weak spot and creeping up in the standings. Each year his machinery gets stronger, he cements ties with good sponsors and gives them their money's worth. In short. Pearson is a charger who won’t be satisfied until he wears No. One.

After a good many seasons of trying to crack the top 10, Terry Poovey finally did it with sixth for the season. Poovey has been on the outside looking in for a good many seasons. Always in the right place at the wrong time or so it seems, Poovey in past years was continually plagued with mechanical problems at just the wrong time like when he was leading. However, put Poovey on a miler and he's all throttle hand. At the double Indy Miles “Pooh Bear” started off with a fifth in round one and then came back in the second running to take the victory, his fifth career National win. Determination is one of Poovey’s strongest traits.

After five years of riding for Ron Wood. Alex Jorgensen deeided to go his ow n way in 1981. It appears to have paid off. For the first time in his career he made the top 10 and he won two Nationals.

When Jorgensen started racing he had a dream. He w anted to win one of every type of dirt track National - short track, TT, mile and half mile. The odds are fairly long on doing that for any but a talented and lucky rider. Not everyone has the talent to be strong on all four.

When Jorgy won at the Sacramento -Mile he was three-fourths of the way to his dream. All he needed was a short track win. Here, the odds became even longer with only two on the schedule. Jorgensen accomplished his feat with a win at Santa Fe.

Afterwards he was calm, as he always is. Jorgy doesn't get fazed easily. In fact, you had to pry the details from him. It was Von, his wife, who had all the dates and plaees on the tip of her tongue. Jorgensen is perhaps the quietest of anyone on the circuit. He is a hard worker, a hard rider and a dedicated rider.

Jay Springsteen did not have a good year. It began with promise. He arrived at Houston in good shape and fine spirits and he won the short track. He won San Jose going away. Then he banged up his hand in a trail riding crash he really likes to ride bikes and was out playing at the time and missed the Ascot TT. Diabetes would get him, then he'd win, then he'd miss a race, then he crashed in the Santa Fe TT, walked off with the Syracuse Mile and the shout was “When he's well, he’s Hell" and he got siek the morning of the second San Jose Mile. Springsteen looked sensational for the final Ascot. In practice he nearly lapped everybody on the track and you could tell it was Springer two turns away . . . so on the first lap of qualifying he went down so hard he had to sit the race out. Damn.

Borderline diabetes doesn't sound that bad. You control it with careful diet, the doctors say. But professional racing isn't the life style or the schedule doctors have ‘ in mind.

The 1979 Winston Pro Champ, Steve Fklund. was after a new approach and program following his eighth place tie in the point standings last year. He left his long-time sponsor Mario Zanotti and joined forces with Storme Winter. Things started off well and Ekiund, who has always been strong at Houston, came away with the TT win. Suddenly, it was shades of 1978 and Springsteen and ETlund were tied on points after the opening Nationals of the year.

Ekiund was hot at the Ascot TT taking, a second and with it a secure hold on the top of the standings. Unfortunately, from there on things went downhill with a string of six straight finishes in seventh or worse. In the midst of that string at the Harrington Half Mile—a track Eklund despises his bad luck string held and he was involved in a crash in his heat, leaving him a spectator.

“Harrington seemed to be the turning point.” said tuner Winter. “Things weren't going good and that just added to the problems.”

The combination should have clicked. Eklund is no slouch on any track and Winter has a reputation for building fast, reliable machinery. At times it seemed the harder they tried the worse things went.

Steve Morehead hovered in and out of the top 10 all season, but couldn't get a string of good placings put together. Two years ago Morehead was hot in the final half of the season; last year he burned up the beginning of the season and then stalled. This time problems, often beyond his control, charted his course. His tuner. Larry Johnson, got sick and was out of action for a good portion of the season. Morehead kept hanging in there, but was frustrated at the little things that always seemed to go wrong.

The high point of the season came at the Harrington Half Mile. Morehead. the defending champ in the event, picked up the win.

There should be some award for bad luck or planning or timing or circumstances and Honda and Freddie Spencer should take home the '81 trophy.

Honda is spending small, okay large, fortunes on the AMA program. But the short trackers didn’t quite work, the XR500-based TT bikes aren't as much better than the others as they were, while the CX500-turned-sideways-with-chaindrive bikes were . . . awful. Nobody knows why. They must have lots ol power and they use the same tires, weigh about what the others do and not even Spencer or Ted Boody could get the V-Twins into the points races. Honda tried dirt track front ends, they tried motocross front ends, they had long exhaust systems and short exhaust systems. For the second San Jose Mile three of the four bikes were tuned to run as Twingles, that is with both cylinders firing nearly together instead of on alternate revolutions. It’s an old tuning trick that sometimes works, but didn’t here.

Two incidents stand out. At San Jose Boodv’s bike worked and he went rolling into the lead in his heat while the Honda wrenches tried to remember how to smile . . . poof. An oil leak put the bike back on the trailer. At the last Ascot Spencer had power and he came slamming past the others and then did everything short of standing on the front axle trying to keep the bike from crow-hopping out of the last line. He couldn’t hold it, the other guys motored away, and once again Freddie was out of dirt track points.

Road racing is part of the Winston Pro series, but not quite because there still isn't much interchange and due to that, the pavement riders have their own seminational title. This year there were five road races, kicking off with the Daytona 200. It was in the 200 that Dale Singleton. “The Pig Farmer” to many, collected his second victory in that event and his third trip to winner’s circle in as many years. No one else has been that consistent in Daytona's annual classic.

Elkhart Fake served as the springboard last year for the first Formula One fourstroke victory (Wes Cooley/Suzuki) and proved again to be a four-stroke delight. This time it was Freddie Spencer collecting his first National win, followed by Honda teammate Mike Spencer and the Suzuki RG500 of Thad WolfT It was the first time in recent memory that a Yamaha has not been in winner's circle.

At Loudon, it was Nick Richichi, grabbing his first National win over Yamaha TZ500 mounted Dale Singleton. The 500s also proved to be very much in the hunt when the show hit Laguna Seca. Suzuki’s GP campaigner Rands Mamola became another first time National winner.

The battle for the United States Road Racing Championship went down to the final round with Singleton and Mike Spencer tied on points. Singleton, wanting the title, took time off from his campaign in Europe to head to the Pennsylvania track. The two ran nose-to-tail for most of the race, the battle being decided by who finished in front of whom. Spencer went down while leading Singleton with just a few laps left and the Pig Farmer took the title home to Dalton, Georgia.

The 1981 season didn't really end until nearly two months after the last race. On the eve of the AMA’s awards banquet Mike Kidd signed a new contract . . .

. . . with Honda. Big Red is determined to win. Honda is planning an all-out assault on Winston Pro events.

That won’t be the only change. The loss of Kidd leaves Yamaha with one contracted rider, Jimmy Filice. That in turn makes Roberts/Lawwill something of too many chiefs for the one Indian. Look for Filice to ride directly for the factory, with C.R. Axtell doing the tuning, and for Roberts/Lawwill to have a reduced role.

Suzuki was nearly invisible in Winston Pro in 1981 and they’re pulling back even more, to concentrate on Superbikes and motocross. Kaw'asaki will fill the gap, wfith Eddie Lawson and Wayne Rainey in road races and-selected dirt events. HarleyDavidson will field a factory team, almost surely with Springsteen and Goss although nothing is official.

More factories, different machines and a whole new set of rivalries w ill make 1 982 even better. ra

1981 AMA WINSTON PRO SERIES POINT STANDINGS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

FEBRUARY 1982 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

FEBRUARY 1982 -

Cycle World

Cycle WorldRoundup

FEBRUARY 1982 -

Features

FeaturesRiding the Winner

FEBRUARY 1982 By John Ulrich -

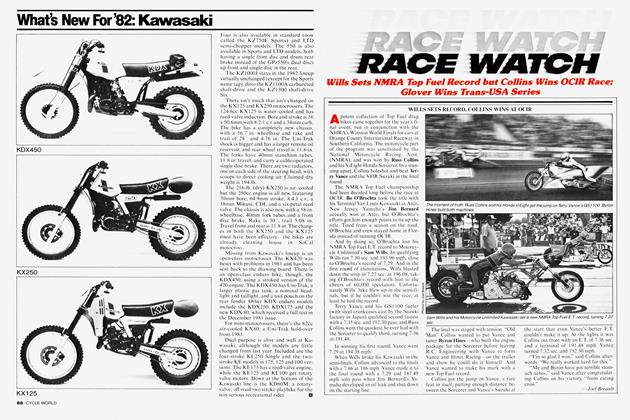

Race Watch

Race WatchWills Sets Record, Collins Wins At Ocir

FEBRUARY 1982 By Joel Breault -

Race Watch

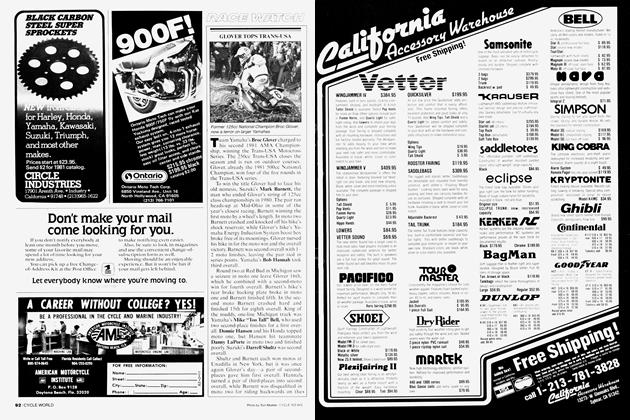

Race WatchGlover Tops Trans-Usa

FEBRUARY 1982 By Tom Mueller