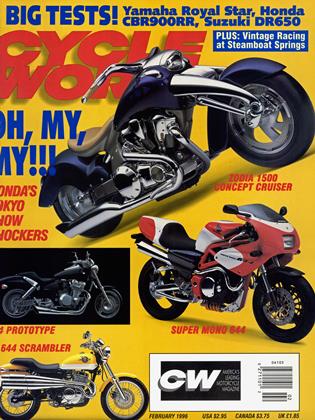

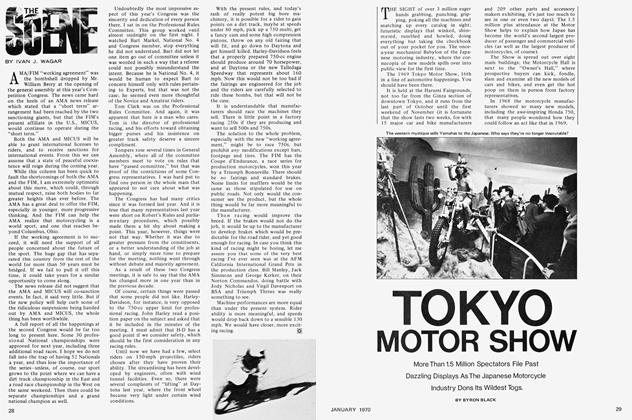

HIGH-FLYIN' HONDAS

DAVID EDWARDS

Are the stars of the Tokyo Motor Show soon-to-come or just a tease?

WHAT WE HAVE here, dear reader, is your basic, Grade A, good news/bad news scenario. Reason for rejoicing; cause for concern. Equal parts triumph and tragedy hang in the air.

On these pages are the motorcycles that stole the thunder at the 31st-annual Tokyo Motor Show, that biyearly trotting out of new models, prototypes and concept bikes by the Japanese Big Four. While Suzuki, Kawasaki and Yamaha were content to merely pull the wraps off their 1996 lineups, Honda trumped ’em all with a wide-ranging collection of fanciful machines, everything from a custom cruiser that would do Arlen Ness proud to a suave little 50cc retro repli-racer.

All of the Hondas bar one will probably see production next year, three show a very strong American influence, but in a sadly ironic twist-no bonus points for getting ahead of us here-there’s a distinct chance that none will make it to the U.S.

Let’s examine the hardware, with commentary by Ray Blank,

American Honda’s assistant vice president, marketing, and the man who plays a big part in the go/no-go decisions about any new model the parent company nominates for importation.

First up, the Zodia 1500, a V-Twin concept cruiser notable not only for its swoopy styling but for its technical accoutrements.

The overhead-cam engine is air-and-oil-cooled, a compact oil radiator tucked behind the stylized grill under the headlight. Valve actuation is via hydraulic camshaft drive, given away by the braided-steel lines running up the cylinders where you might expect to see pushrod tubes on an ohv motor. Power makes its way via automatic transmission along a drive chain to a sprocket hung on the end of an aluminum, single-sided swingarm. Check out the brakes: rim rotors, the front pinched by a trick eight-piston caliper. ABS and Honda’s linked activation, of course. This is a cruiser with engineering credentials. It’s also a runner.

“A real interesting piece,” says Blank. “It’s a concept bike, but it’s not a woodenengine monster. If Honda wanted to build this, it could be done with current technology.”

Blank says the Zodia came as a complete surprise; in previous visits to Honda’s Asaka styling studios, there was no evidence of the bike. Hmmm. Perhaps the Zodia was started as a rogue project a la the RC30 repliracer, an after-hours affair by a group of employees chagrined by the underengineering involved in producing the current Harley-clone ACE 1100 cruiser? As if they’re saying, “Okay, you want cruisers, we can do cruisers.

But’s let’s have some fun,

let’s do it right, expand horizons, not just follow a blueprint laid down by someone else.”

Blank does not offer an opinion. He does say that the Zodia likely won’t be pasted into Honda’s production catalog any time soon, noting it inhabits the “outer edges of the circle...It looks gorgeous, radical, but I’d say it’s more of a design direction than a place to step off.”

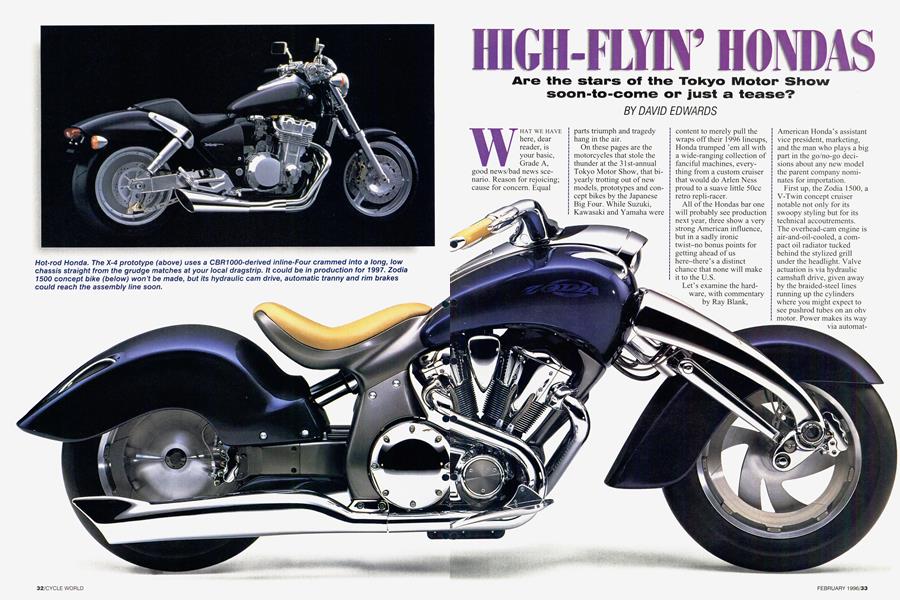

Not so with the next Honda show-stealer, a dragstrip-derived creation described in press releases as a “performance naked American model,” which brings all kinds of entertaining imagery to mind.

Says Blank, “This is not a dreambike. It’s close to reality right now.”

The X-4 uses a lOOOcc, liquid-cooled inline-Four, the same powerplant employed in the CBR1000F sportbike and, in detuned form, the CB1000 retrostandard. This is a full-metal motorcycle, from its soliddisc rear wheel to its extruded-aluminum swingarm to its shrouded twin shocks to its

tank-top speedometer binnacle. Exhaust gases get spit through a chromed 4-into-l sidewinder pipe.

Blank sees the X-4 as the next progression of the CB1000, never a big seller in the U.S. Now, sales worldwide have softened, too, and the X-4’s mission is to pump some gusto into the large-cc retro class.

Europe and Japan will likely see the bike in showrooms for the ’97 selling season.

What about us?

“If I had to guess, I would say no,” says Blank, adding, “If it’s a powerhouse, it’s got a chance, but not if it’s just a big-bore machine with only average power. It’s got to be a snorter.”

Biggest stumbling block, though, may be America’s reluctance to cuddle up to yester-bikes.

“You can only look at old stuff for so long before old stuff starts to look old,” notes Blank in the finest tradition of that esteemed philosopher Yogi Berra.

Okay, what about something a little more modem, something like the Hornet 250, a Japan-spec 1996 model that debuted at Tokyo?

Describing the diminutive four-cylinder, with its slinky, high-exit exhaust, as a “great new kind of naked look,” Blank nonetheless shoots down any possibility of it coming to the U.S. of A.

That’s no surprise, but squint at the Hornet’s photo, imagine it stretched a few inches in every direction and with a 600cc lump jacked into its engine bay. Better yet, a 750 model. Might that be a mid-1990s version of the CB750 K0, the original do-anything, all-purpose Four that knocked the motorcycle world for such a loop 25 years ago?

“Could be, though I can’t really talk about it,” says a suddenly evasive Blank. Pressed, he admits that American Honda recently had an upclose look at the Hornet 250. “The problem is price,” he relates. “Dressed as it is, we’re talking in the $5000 range. As a 600 or 750, it’d be $6500. That’s very questionable.”

Which brings us to the Super Mono 644 and CL644 Scrambler, officially listed as “exhibition models,” but obviously very close to production status. Both are built around the electric-start, aircooled, four-valve, sohc Single familiar to us as the powerplant in the XR650L dual-purpose bike.

The Super Mono, in particular, is sexier than seamed stockings and stiletto heels. Its S-bend header pipes and twin, highrise mufflers impart a certain 1960s cafe-racer flair; the trellis-style main frame hints at Ducati; up front, a thoroughly modern upsidedown fork provides a good home for monster discs and | a pair of Nissin four-pot calipers. And the visual thrills don’t stop there. Note the under-engine shock (thank you, Messrs. Buell and Britten), attached at one end to a braced, ovaltube, polished-aluminum swingarm, the other to a couple of milled alloy plates. All very cool.

“I love the concept,” says Blank, estimating the bike’s price tag at between $5500 and $6000. “My heart tells me we should bring it in.” There’s a roadblock the size of a jack-knifed Peterbilt in the way, though.

“It’s a Single,” states the man who once green-lighted the GB500 one-lunger, a Brit knockoff that met with only lukewarm response. “In most markets, the Super Mono would do very well, but no one’s been successful with a Single here.”

But something as sultry as the Super Mono would find buyers over here, surely. There must be at least 1000 Singles fans ready to commit. Hell, you could sell a six-pack of the damn things right here at 1499 Monrovia Ave. just like that.

Too expensive to try just 1000 units, counters Blank. Figure in U.S. homologation (as high as $100,000 per bike), plus the cost of stocking parts and bodywork, printing American-spec owners manuals, drawing up marketing plans, creat-

ing advertising-in j short, Honda is not in the ¡ boutique-bike business, j “It just doesn’t pay, unless j you’re doing it for image, j for racing or for some other j reason,” Blank says, j There’s more hope for the j CL644, a modem rendition j of the immensely popular j 250 and 305 Scramblers of j the 1960s. These were i everywhere back then. And j talk about all-American:

I Roy Rogers, King of the j Cowboys, even rode a Honda Scrambler, rifle scabbard lashed to a fork tube, for cry in’ out loud.

“It’s a real, honest, straightforward ‘motorsickle’,” says Blank, noting that back at American Honda headquarters in Torrance, California, there’s “more support for the CL than for the Super Mono...If there’s a possibility of us having one of these, this is the one we’d have.” But it’s a long shot, he admits.

So, what are we to take away from the Tokyo Motor Show, besides the slim possibility of us having a crack at these intriguing new models? Well, as Big H approaches the 50th birthday of founding father Soichiro Honda’s first rickety, turpentine-burning motorbike, maybe nothing more complicated than simple, subtle reaffirmation.

“Honda had turned into a car company with a motorcycle division,” says Blank, without going into detail about the dark days of the mid-to-late 1980s, when it seemed the company was doing everything in its power to get out of the motorcycle business.

“Tokyo showed that Honda is first a motorcycle company that builds cars, too. I’m very proud for my company to show itself in this way.”

Bottom line, says Blank: “This is a company that is in love with motorcycling, and I think it shows.”

Not a bad message, really. Here’s hoping Honda decides to send a little love our way.