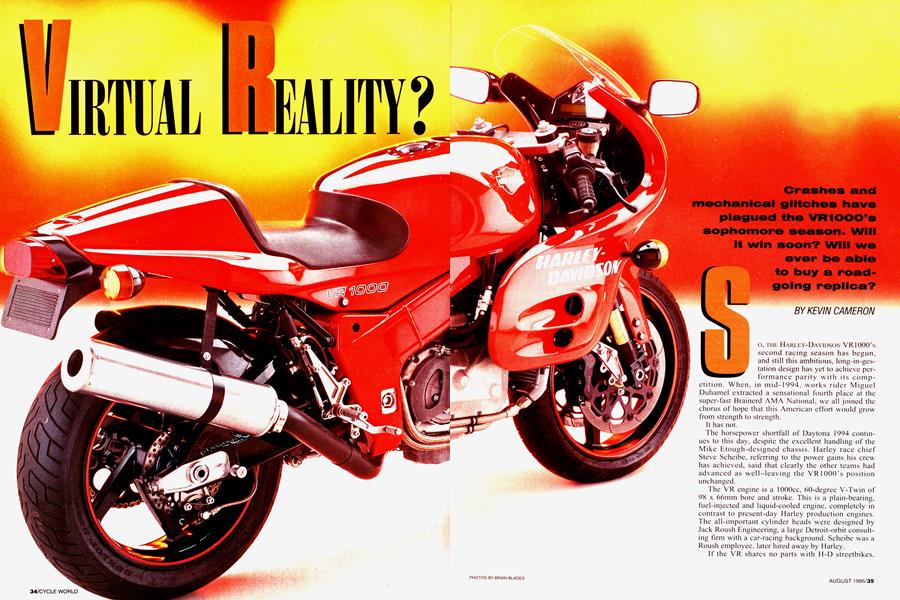

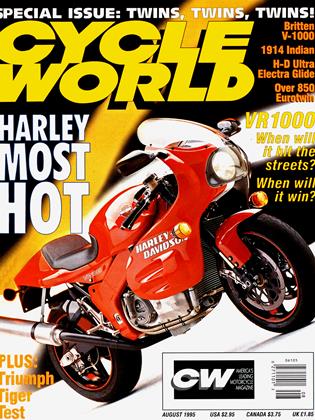

VIRTUAL REALITY?

Crashes and mechanical glitches have plagued the VR1000's sophomore season. Will it win soon? Will we ever be able to buy a road. going replica?

KEVIN CAMERON

So, THE HARLEY-DAVIDSON VR1000’S second racing season has begun, and still this ambitious, long-in-gestation design has yet to achieve performance parity with its competition. When, in mid-1994, works rider Miguel Duhamel extracted a sensational fourth place at the super-fast Brainerd AMA National, we all joined the chorus of hope that this American effort would grow from strength to strength.

It has not.

The horsepower shortfall of Daytona 1994 continues to this day, despite the excellent handling of the Mike Etough-designed chassis. Harley race chief Steve Scheibe, referring to the pow’er gains his crew has achieved, said that clearly the other teams had advanced as well-leaving the VRIOOO’s position unchanged.

The VR engine is a lOOOcc, 60-degree V-Twin of 98 x 66mm bore and stroke. This is a plain-bearing, fuel-injected and liquid-cooled engine, completely in contrast to present-day Harley production engines.

I he all-important cylinder heads were designed by Jack Roush Engineering, a large Detroit-orbit consulting firm with a car-racing background. Scheibe was a Roush employee, later hired away by Harley.

If the VR shares no parts with H-D streetbikes, how did it get homologated for AMA racing, in which machines must be “as sold for normal highway use?” Aha! The rule says nothing about where machines are sold for highway use; the VR is, in fact, homologated through a “country of convenience.” Poland, in this case.

End runs around the rules notwithstanding, there is expectation of better than a fourth place after seven years’ work. California airflow specialist Jerry Branch, whose enthusiasm and unsolicited design work were a part of the VR’s dim past, sees the project as stalled, an administrative catastrophe in which the Not Invented Here concept is enough to eliminate everything but the company way. At least some others seem to agree with him. The picture they paint is of discontent with the VR project. They see it surrounded by a curtain of silence, immune to criticism or even open discussion. There is even suggestion that there are forces within the company ready to push a winor-quit policy.

At this point, no one will say whether the VR could be Harley’s spearhead into the sportbike market, now left wide-open by the high value of the Japanese yen. The mere existence of the bike on the cover of this issue says it may. The fact that a Harley executive rode such a street-equipped VR to the 1994 Road America AMA national also says it may. The fact that Erik Buell is on familar terms with the VR’s engine-mount holes seems to say so, too. But if the VR fails on the track, can its children succeed in the showroom? The critics charge that the VR cries out for the talents of the American motorcycle racing community at large, but the project is quarantined away from outside influence, they say, by Scheibe and the man he reports to, engineering VP Mark Tuttle.

But turn that coin over. In any company, racing notoriously tends to become a corporate political football. Racing is pumped-up when the pro-racing forces in the company are in power, shut off tight when the perpetual arm-wrestle goes against them. Knowing this, wouldn’t a sensible director try to isolate a racing program from this kind of thing? Scheibe was surprised at insinuations of political powerplays, saying, “I don’t sense that. I don't get any pressure like that.”

Later in the conversation, he summed up his position thusly: “Our main focus has been reliability.”

So, swirling controversies-if they exist-must swirl in another, distant world. I had the impression of a man at his work, far from the winds and waves of corporate policy. Of the notional “curtain of silence,” he said, “It’s (the VR project) pretty much separate from the company. I’m aware that it wasn’t bought-into by the whole company. But I think there are three reasons for that separation: (1) Engineering likes it that way. The way we do things in racing interferes with their process. We have to look for ways to get 90 percent of the benefit in 10 percent of the time; (2) Racing likes it that way. We can’t back every single thing we do with documentation like they (Engineering) have to, and (3) When the early results weren’t so promising, we got a lot of negative press. That made us less inclined to be talkative.”

None of this tells us whether or not the VR is where it should be, or what may be done about it. CW's European Editor Alan Cathcart learned that one or more VR engines has been seen at Brian Hart Engineers, Ltd., a 25-man English shop specializing in engine design and development, and that a complete VR machine has been seen at Lotus. This has led to the speculation that a “Mk.II” cylinder head is in development. Scheibe says that no such development is known to him.

Is a new head needed? When Dick O’Brien (the previous Harley racing manager, now retired), first saw the VR pieces, he remarked on the huge size of the intakes, and the absence of flywheel weight. Scheibe says the intakes were designed to a mean velocity at peak power rpm of 250 feet per second. He says this is low by comparison with the 375 fps of current European/F-1 practice, but very comparable with Japanese Superbike designs. From 1994 onward, the VR intakes have been somewhat filled with CNC-sculpted white epoxy to raise velocity about 60 fps, but Scheibe has experimented with even higher port velocities. Result? Perhaps 2 more horsepower in the 7000-to-8000 range, but a 5-horsepower drop on top. No mystery fix.

Is the VR sighting at Lotus a bid for a quick fix? If it’s true, it’s more likely just the normal corporate practice of getting second and third opinions. And the possible subject of enquiry? Perhaps racing-related, but more likely estimation of what VR features would be unsuitable for production. Earl Werner, now head of H-D engineering, comes from Corvette, which has historical ties with Lotus. Another recent rumor: Harley personnel seen at Porsche, in Germany. Answer: Harley has ties with Porsche, which designed the engine for the stillborn Nova project. Look in the SAE newsletter and learn that Harley is hiring powertrain engineers. New projects mean new engineering needs.

Just w'hat is the VR’s performance shortfall? Until we can bring a 955 Ducati, a Kawasaki ZX-7R and the VR1000 together, race-ready, in a same-day, samedyno comparo, no one knows. At Brainerd last year, Scheibe reckons it was 6 mph on top. At Daytona this year, it was more like 10 mph. Power requirement rises approximately with the cube of speed, so this translates to between an 11 and 20 percent power difference. If the top Superbikes make 140 or so rear-wheel horsepower, this would be 15-28 horsepower. That would put the VR down at 112-125, rear-wheel.

All this is very perplexing, because the VR has, physically, all the makings of success. It has a chassis of outstanding stiffness, whose handling has been praised by everyone who has ridden it. It has the full lOOOcc that the rules allow, with proven mechanical strength to reach competitive rpm in the 11,000 range. The engine is a compact, rigid design that fits a race chassis better than the wide-Vee Ducati engine. Above all, it is backed by a prosperous company with the means to fund fast, effective development.

Where’s the beef?

Okay, how much beef should there be? We can estimate this by using the engine’s rpm capability, its displacement and commonly attained averaged combustion pressure. When we put in the numbers, we find that there was nothing wrong with Jerry Branch’s initial 1987 estimate that an engine of this type could make 165 horsepower. And if the stroke were shortened in F-l GP style to raise revs into the twilight zone, this expectation could rise to the vicinity of 180 horsepower. These are crankshaft horsepower, so subtract 10 percent or so for transmission loss-160 and 180 then become 144 and 162 rear-wheel prancers. That’s beef, all right, but imaginary.

Next item: Scheibe’s shop employs five people. Have you seen those promo movies in which hundreds of Japanese technicians perform 7 a.m. calisthenics, singing the company song, before going on-shift at the R&D center? Big difference. “It takes so long to do anything,” Scheibe remarked before Daytona this year. “You have to take the heads off, the pan, the rods. Then you do whatever you have to do and put it all together.” Although he didn’t say it out loud, what I heard was “not enough people.” Scheibe's small group has enough to do just getting ready for the next race. Engine development must be fitted into the crevices in this schedule. Money is being spent, but much of it must go to outside suppliers.

To date, the failures have been details, not basic design. At Daytona ’94, there were clutch-hub breakages (the hubmaker said no torsional shock absorber was needed), fuelpump heating problems, and a “de-phased" engine balancer (it destroyed the engine right at start-finish in the race). There have been fatigue failures of the cam primary chain, leading to cam breakages and chain-guide failures. A newtype piston broke up at Pomona this year. Still, for a new bike, this is not a bad record.

Since the ’94 season, the design has been cleaned-up with a view' to serviceability. Now the battery and computer are in the nose, with all components sitting on custom-made carbonfiber trays, positioned by pegs in rubber grommets, secured by quarter-turn fasteners. There is a new integrated wiring harness in place of the lasso-like loops of miscellaneous wire from 1994 (which existed to serve the engine both on the track and on the dyno). The engine air intake is under the steering head, and a nice diffuser converts velocity to pressure on the way to the enclosure around the intake stacks. Airbox volume has been increased, which may have somewhat reduced the power drop caused by installing the seat/tank unit over the big vertical injector stacks. These are thoroughly professional-looking parts, fabricated by Roush or its suppliers.

During a Cycle World visit to the race department, Scheibe described some of the amazing phenomena that occur with fuel injection. It’s often assumed that modern injection, because it is controlled by a computer and addressable by keyboard, is technologically “clean,” with no rough edges. Program the fuel flowyou want-and get exactly that.

The truth is different. Injected fuel is less well atomized than carbureted fuel because carbs bleed air into the fuel stream, breaking it up finely. To counteract this, injected fuel must be given extra time in which to break up and evaporate. When CoventryClimax switched its F-l auto racing engine to injection back in 1961, it had to place the injectors up in the air, actually above the open ends of the intake stacks.

When a pair of intake valves open and a suction cycle begins, a wave of low' pressure from the cylinder rushes out through the intakes and into the intake pipe. If the intake pipe length is correct for the rpm the engine is turning, after one or more reflections a positive pressure wave will return to the engine just as the intakes are closing.

This last-moment rise in intake pressure at the valves stuffs some extra mixture into the cylinder.

Scheibe says, “The torque can rise 57 foot-pounds when you hit the right tuned length” (this is 10 or more horsepower at peak revs). Of equal interest:

The presence of vigorous w'ave action in the intake pipes pushes fuel back out of them to form a cloud of vapor that is called “stand-off.” Of this, Scheibe says, with a wry look, “Whenever the stand-off is at a maximum-even with clouds of fuel drifting away in the wind from the dyno fan-that’s best power.”

But this free gift isn’t free. Scheibe says that a torque graph clearly shows the peaks and valleys caused by intake-wave action; there are almost three sets of peaks and valleys between 6000 and 10,700 revs. You can see why race-engine designers are working with variable intake length. With it, the whole torque curve rises essentially to the peak figures-but without the valleys.

The VR race shop has just been relocated away from the tradition-laden brick complex on Juneau Avenue, to a nearby industrial park. Part of the new setup is Kistler electronic pressure-tracing equipment, for use in intake, exhaust and combustion chamber. Scheibe says, “My first point of study is the exhaust system.

Intake pressures (recorded on the new equipment) looked marvelous. The exhaust, I’m not pleased with.” At Daytona this year, you could see work in progress; the original megaphoned collector with a muffler on its end, and a new 2into-2, in which the pipes come close and are joined by four little cross-tubes. The race shop was full of heat-discolored experimental exhaust systems in February. Since then, there has been little time for development work.

So, what can we conclude? Is VR success just around the corner? Probably not. It is coming, slowly but surely? The track results say no again, but Steve Scheibe believes the VR is viewed inside the company as being on-track, making satisfactory progress. Seething discontents, if any? Take your pick. Racing is attractive, so people want to be part of it. As a project grows, some ideas are selected, others are dropped. Egos swell and shrink. Turf is claimed, and fought over. There are internal winners and losers. Money has to be accounted for. Strong feelings reverberate, then become policy. The customary thick layer of PR bondo is troweled-on in hopes of making the human drama look as well-controlled as a studio photo shoot. It never does.

We still believe in American ingenuity and practical problem-solving, and we hope they are seen up front. Soon.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontOklahoma Hits Home

August 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsGood Company

August 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThunder Bolts

August 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupBritten To Build Indians

August 1995 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupBikes Will Be Made In the Usa, Says Indian's New Chieftain

August 1995 By Alan Cathcart