GP BUMBLEBEE

American FLYERS

Rossi meets Roberts

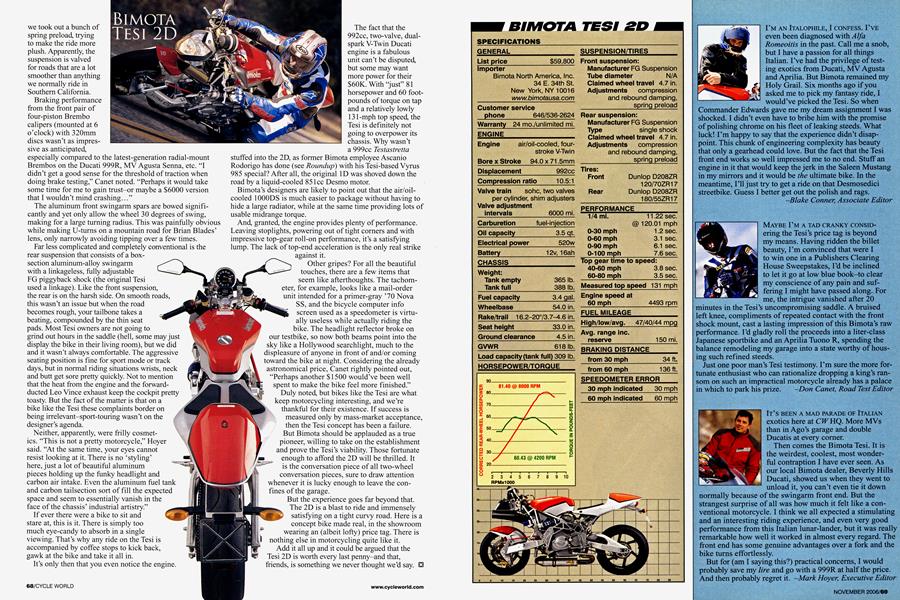

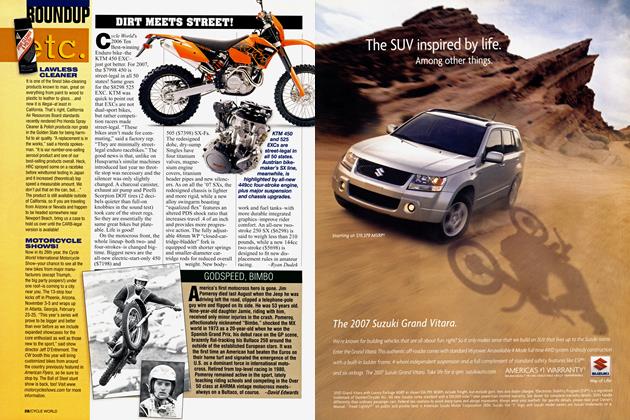

YAMAHA, DURING ITS 50th-anniversary year, liveried their MotoGP M1s for the Laguna Seca round in this classic 1970s U.S. team paint scheme. This brought sharp double-takes from those old enough to have seen Kenny Roberts, Gene Romero and others on two-stroke 250s, 350s and 750s with this paint. Dig deep and you find the yellow-and-black goes all the way back to New England Yamaha dealer John Jacobson and his 1969 team of privateer racers.

The Yamaha Ml has evolved rapidly since the coming of the experienced duo of Valentino Rossi and crew chief Jeremy Burgess. Technology is useless without coherent direction. In MotoGP’s short history we have seen more than one company work very hard and get nowhere-or even go backward. Pneumatic valves, ultra-revs and super light weight accomplish nothing if the machine is difficult to ride. Rapid progress requires big-company resources, guided by a top rider who understands how motorcycles work, and by a trackside staff equally fluent in engineering and racing.

There is nothing radical to see here. The latest Ml engines have four valves serving each of their four cylinders. Gear cam drive has replaced the former chain-plus-gear drive. Firing order has been altered from the normal 180 degrees of a classic inline-Four to a “twisted crank” order that produces the pulsating torque that tires seem to like. In 2004 Rossi won the title through a combination of virtuoso riding and crashprogram redirection of R&D toward the goal of creating a smooth, rideable torque curve. Although the machine was often down 5-10 clicks in top speed versus the Honda RC211 s, its smooth off-corner drives more than made up for this.

By 2005 Yamaha had caught up in sheer power, and Honda had divided its own effort. While Honda press releases forecast a bright future for its 2006 team of younger riders,

Rossi made hay and won another world title.

Much has been made of the electronic revolution that has helped to make these bikes as fast and stable as they are. Yamaha and Honda have employed automatic controls only as needed to supplement the basic rideability built into their engines. If the rider misjudges his drive and the tire begins to break traction, the computer detects this and softens the torque delivery via a menu of methods. First-fastest and smoothest-is electronic ignition retard, followed by limited fuel lean-out and backed up by fast stepper-motor control of two or more of the engine’s throttle plates. A favorite trackside game of moto-joumalists is to stare fixedly at riders’ left hands-to see who is using the clutch and who is instead relying on the computer and on-board clutch/gearchange actuators.

This machine has a muffler instead of the now-legal megaphone seen on many bikes. Rossi doesn’t like the noise-it’s distracting. Trackside personnel agree, but noise sells tickets. Clearly, peak power no longer rules. The close firing order gives these machines a low growl rather than the high and musical howl-withovertones of classic 1960s megaphones. Progress is not always romantic.

The smaller that engines can be made, the more easily their mass can be located where it’s needed-forward. Yamaha’s R1 sportbike began the practice of “stacking” gearbox shafts vertically, which makes engines more compact front-to-back. That concept is seen here, allowing the longer swingarm that eases suspension setup compromises.

As if we didn’t know, racing reminds us that nothing and no one can be perfect. At Laguna this past summer, Rossi didn’t win. He didn’t even finish second. Two men who knew Laguna better than he did finished ahead of him-Nicky Hayden first on Honda, then Rossi’s teammate, Colin Edwards.

Kevin Cameron

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe New Guy

November 2006 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsReturn of the Scrambler

November 2006 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCBack To Nature

November 2006 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2006 -

Roundup

RoundupBoulevard Bruiser

November 2006 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupComing Soon: Monster 695

November 2006 By Bruno Deprato