LEANINGS

Glowing inspirational restoration messages

Peter Egan

As I CLIMBED INTO MY SALT-SPATTERED van and headed down our driveway yesterday afternoon, I almost had to laugh (but not quite) at the sheer dismalness of the winter day: dark and wet with heavy fog and big snow clumps flopping out of trees (Fap!). The radio said all major Midwestern airports were closed down with peasoup fog.

Not exactly riding weather, but a good motorcycle day of another kind, nonetheless.

I was a man with a mission. In my pocket was a shopping list of unlikely items that would probably have confused the layman: 50 lb. Grainger glass polishing beads, #610G98; 1 gallon DuPont Kwik Prep metal primer 244S; p/u bronze swingarm bushings at Wisconsin Bearing; 1 tube Tripoli buffing compound, Farm & Fleet.

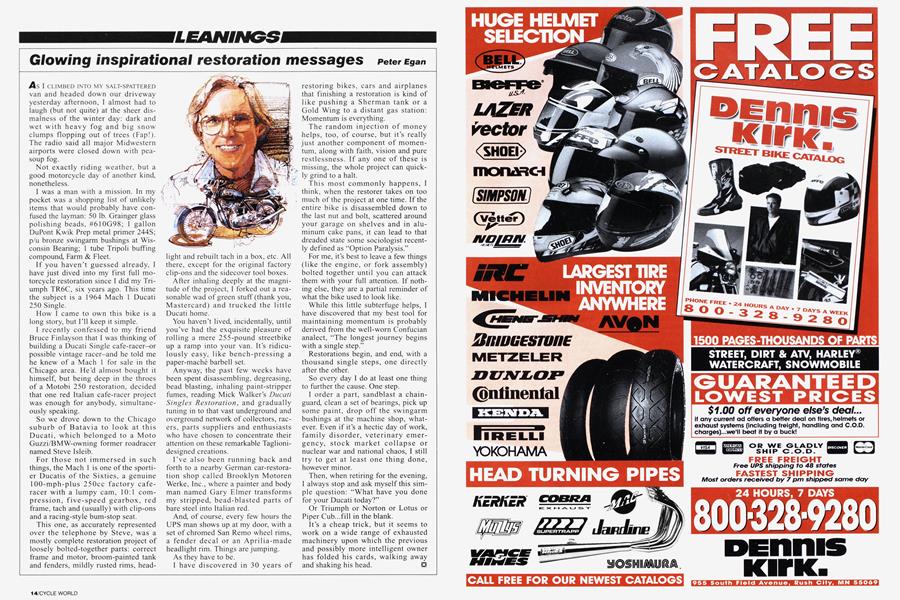

If you haven’t guessed already, I have just dived into my first full motorcycle restoration since 1 did my Triumph TR6C, six years ago. This time the subject is a 1964 Mach 1 Ducati 250 Single.

How I came to own this bike is a long story, but I’ll keep it simple.

1 recently confessed to my friend Bruce Finlayson that 1 was thinking of building a Ducati Single cafe-racer-or possible vintage racer-and he told me he knew of a Mach 1 for sale in the Chicago area. He'd almost bought it himself, but being deep in the throes of a Motobi 250 restoration, decided that one red Italian cafe-racer project was enough for anybody, simultaneously speaking.

So we drove down to the Chicago suburb of Batavia to look at this Ducati, which belonged to a Moto Guzzi/BMW-owning former roadracer named Steve Isleib.

For those not immersed in such things, the Mach 1 is one of the sportier Ducatis of the Sixties, a genuine 100-mph-plus 250cc factory caferacer with a lumpy cam, 10:1 compression, five-speed gearbox, red frame, tach and (usually) with clip-ons and a racing-style bum-stop seat.

This one, as accurately represented over the telephone by Steve, was a mostly complete restoration project of loosely bolted-together parts: correct frame and motor, broom-painted tank and fenders, mildly rusted rims, headlight and rebuilt tach in a box, etc. All there, except for the original factory clip-ons and the sidecover tool boxes.

After inhaling deeply at the magnitude of the project, I forked out a reasonable wad of green stuff (thank you, Mastercard) and trucked the little Ducati home.

You haven’t lived, incidentally, until you've had the exquisite pleasure of rolling a mere 255-pound streetbike up a ramp into your van. It’s ridiculously easy, like bench-pressing a paper-maché barbell set.

Anyway, the past few weeks have been spent disassembling, degreasing, bead blasting, inhaling paint-stripper fumes, reading Mick Walker’s Ducati Singles Restoration, and gradually tuning in to that vast underground and overground network of collectors, racers, parts suppliers and enthusiasts who have chosen to concentrate their attention on these remarkable Taglionidesigned creations.

I’ve also been running back and forth to a nearby German car-restoration shop called Brooklyn Motoren Werke, Inc., where a painter and body man named Gary Elmer transforms my stripped, bead-blasted parts of bare steel into Italian red.

And, of course, every few hours the UPS man shows up at my door, with a set of chromed San Remo wheel rims, a fender decal or an Aprilia-made headlight rim. Things are jumping.

As they have to be.

I have discovered in 30 years of restoring bikes, cars and airplanes that finishing a restoration is kind of like pushing a Sherman tank or a Gold Wing to a distant gas station: Momentum is everything.

The random injection of money helps, too, of course, but it’s really just another component of momentum, along with faith, vision and pure restlessness. If any one of these is missing, the whole project can quickly grind to a halt.

This most commonly happens, I think, when the restorer takes on too much of the project at one time. If the entire bike is disassembled down to the last nut and bolt, scattered around your garage on shelves and in aluminum cake pans, it can lead to that dreaded state some sociologist recently defined as “Option Paralysis.”

For me, it’s best to leave a few things (like the engine, or fork assembly) bolted together until you can attack them with your full attention. If nothing else, they are a partial reminder of what the bike used to look like.

While this little subterfuge helps, I have discovered that my best tool for maintaining momentum is probably derived from the well-worn Confucian analect, “The longest journey begins with a single step.”

Restorations begin, and end, with a thousand single steps, one directly after the other.

So every day I do at least one thing to further the cause. One step.

I order a part, sandblast a chainguard, clean a set of bearings, pick up some paint, drop off the swingarm bushings at the machine shop, whatever. Even if it’s a hectic day of work, family disorder, veterinary emergency, stock market collapse or nuclear war and national chaos, I still try to get at least one thing done, however minor.

Then, when retiring for the evening, I always stop and ask myself this simple question: “What have you done for your Ducati today?”

Or Triumph or Norton or Lotus or Piper Cub...fill in the blank.

It’s a cheap trick, but it seems to work on a wide range of exhausted machinery upon which the previous and possibly more intelligent owner has folded his cards, walking away and shaking his head. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontLove At First Ride

May 1995 By David Edwards -

TDC

TDCThe Mpg Papers

May 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's Storming Standard

May 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupTriumph's Getting Tubular, Going Raging

May 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha To Fork It Over Once More

May 1995 By Robert Hough