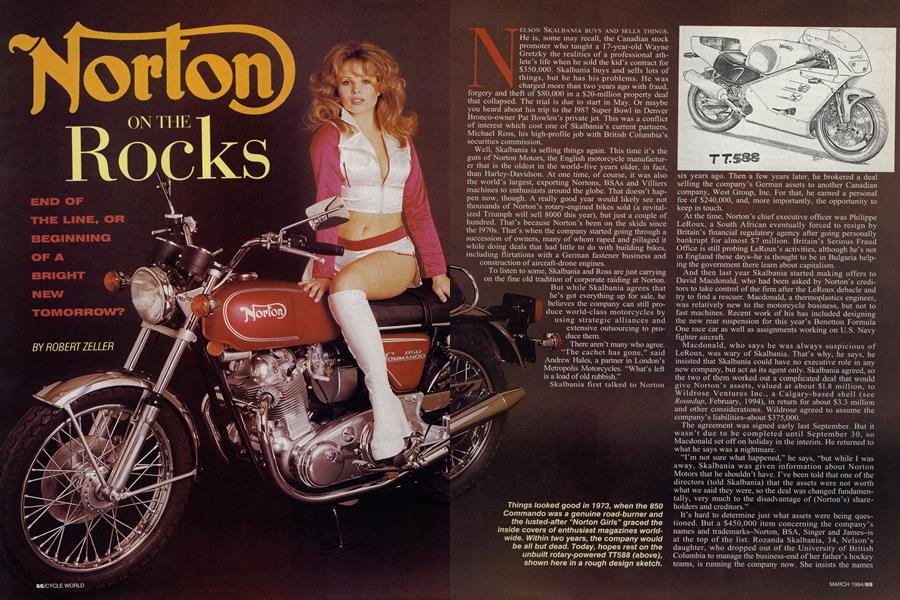

Norton ON THE Rocks

END OF THE LINE, OR BEGINNING OF A BRIGHT NEW TOMORROW?

ROBERT ZELLER

NELSON SKALIBANIA BUYS AND SELLS THINGS. He is, some may recall, the Canadian stock promoter who taught a 17-year-old Wayne Gretzky the realities of a professional athlete's life when he sold the kid's contract for $350,000. Skalbania buys and sells lots of things, but he has his problems. He was charged more than two years ago with fraud,

forgeiy and theft of S80,000 in a 520-million property deal that collapsed. The trial is due to start in May. Or maybe you heard about his trip to the 1987 Super Bowl in Denver Bronco-owner Pat Bowlen's private jet. This was a conflict of interest which cost one of Skalbania's current partners. Michael Ross, his high-profile job with British Columbia's securities commission.

Well, Skalbania is selling things again. This time it's the guts of Norton Motors, the English motorcycle manufactur er that is the oldest in the world-five years older, in fact, than Harley-Davidson. At one time, of course, it was also the world's largest, exporting Nortons, BSAs and Villiers machines to enthusiasts around the globe. That doesn't hap pen now, though. A really good year would likely see not thousands of Norton's rotary-engined bikes sold (a revital ized Triumph will sell 8000 this year). but just a couple of hundred. That's because Norton's been on the skids since the 1970s. That's when the company started going through a succession of owners, many of whom raped and pillaged it while doing deals that had little to do with building bikes, including flirtations with a German fastener business and construction of aircraft-drone engines.

To listen to some, Skalbania and Ross are just carrying on the fine old tradition of corporate raiding at Norton.

But while Skalbania agrees that he's got everything up for sale, he believes the company can still pro duce world-class motorcycles by using strategic alliances and extensive outsourcing to pro duce them.

`~J1 There aren't many who agree. `The cachet has gone," said Andrew Hales, a partner in London's Metropolis Motorcycles. "What's left is a load of old rubbish."

Skalbania first talked to Norton

six years ago. Then a few years later, he brokered a deal selling the company's German assets to another Canadian company, West Group, Inc. For that, he earned a personal fee of $240,000, and, more importantly, the opportunity to keep in touch.

At the time, Norton's chief executive officer was Philippe LeRoux, a South African eventually forced to resign by Britain's financial regulatory agency after going personally bankrupt for almost $7 million. Britain's Serious Fraud Office is still probing LeRoux's activities, although he's not in England these days-he is thought to be in Bulgaria help ing the government there learn about capitalism.

And then last year Skalbania started making offers to David Macdonald, who had been asked by Norton's credi tors to take control of the firm after the LeRoux debacle and try to find a rescuer. Macdonald, a thermoplastics engineer, was relatively new to the motorcycle business, but not to fast machines. Recent work of his has included designing the new rear suspension for this year's Benetton Formula One race car as well as assignments working on U.S. Navy fighter aircraft.

Macdonald, who says he was always suspicious of LeRoux, was wary of Skalbania. That's why, he says, he insisted that Skalbania could have no executive role in any new company, but act as its agent only. Skalbania agreed, so the two of them worked out a complicated deal that would give Norton's assets, valued at about $1.8 million, to Wildrose Ventures Inc., a Calgary-based shell (see Roundup, February, 1994), in return for about $3.3 million and other considerations. Wildrose agreed to assume the company's liabilities-about $375,000.

The agreement was signed early last September. But it wasn't due to be completed until September 30, so Macdonald set off on holiday in the interim. He returned to what he says was a nightmare.

"I'm not sure what happened," he says, "but while I was away, Skalbania was given information about Norton Motors that he shouldn't have. I've been told that one of the directors (told Skalbania) that the assets were not worth what we said they were, so the deal was changed fundamen tally, very much to the disadvantage of (Norton's) share holders and creditors."

It's hard to determine just what assets were being ques tioned. But a S450,000 item concerning the company's names and trademarks-Norton, BSA, Singer and James-is at the top of the list. Rozanda Skalbania, 34, Nelson's daughter, who dropped out of the University of British Columbia to manage the business-end of her father's hockey teams, is running the company now. She insists the names are, at worst, worthless. At best, she says, the cost of regaining control of them wnuld Fw~ horrendous.

“We thought we had the names (protected) worldwide,” she explains. “But so many of those registrations have lapsed, we’re going to have to fight to get them back. People have been using the names and capitalizing on them for years.’

Not everyone agrees. Some believe that the continued use of the Norton name by outsiders, even if it was without approval, kept the Norton mystique alive when few bikes were being sold. But that doesn’t wash with Rozanda. “Well, if they were paying royalties,” she says through somewhat clenched teeth, “the company would still be alive.”

The modified deal put together by Skalbania and the absent Macdonald’s co-directors still gave Wildrose the company. But as compensation for the perceived downsizing of assets, Wildrose’s obligations to Norton’s creditors was dropped. And in the meantime, a required $3.5 million cash injection by Wildrose was not made because trading in Wildrose stock had been halted by the Alberta Stock Exchange.

Today, at Norton’s plant at Shenstone, in Staffordshire, near Birmingham, they’re not hanging the crepe-yet. But the joy has gone, as have most of the employees. For the skeleton staff that remains, and for many others, there is doubt that the company will be able to stay afloat.

One man who speaks quietly and with confidence is Richard Negus, now Norton’s general manager and the company’s only engineer. Negus, 50, has been around Norton for a long time, and he has been in the motorcycle business even longer. But his task is awesome. Plans to

introduce the stunning F2, shown at the 1992 NEC show in Birmingham, had to be dropped. The bike was a non-running design study, not at all practical to produce, and while the company got plenty of positive reaction to the bike, it got no orders. It did, however, receive orders for 50 TT588s, the design for which is not yet complete. The lights in Negus’ office will still bum late when the TT588 is finished, because he’ll have to reemploy laid-off plant workers and then find a market for another 150 bikes before December to fulfill the new management’s production target.

And even though much of the work will be subcontracted-wheels will come from Germany and suspension components and brakes from Italy-it’s going to be unbelievably difficult. The company, which once had one of the finest engine-research departments in Britain, now doesn’t even have a draftsman. It simply hasn’t the resources to do its engine work in-house.

It is the same for testing. This will be done in Germany—not by Norton engineers, but by a journalist who is doing it free to get a story for his magazine. “We cheat,” says Negus with a smile. “The journalist came to us for an interview, but we’ll get even more from him.”

But the company can only cheat so much. With so many creditors left unpaid, there isn’t much goodwill left with outside suppliers, and many of those who will still sell to Norton demand cash before their delivery trucks get unloaded.

One possibility that Rozanda Skalbania is pushing is that of forming strategic alliances with other companies in related fields. She’s confident that in recession-ridden England, where there are numerous companies with lots of underutilized manufacturing space and plenty of skilled employees, she can locate at least one that could benefit from Norton’s rotary-engine expertise. Cash-poor as it is, it’s the only manufacturer, other than Mazda, building rotaries, and the company has enormous ability to offer. Or even sell. Recently a new rotary engine design went to Infinite Machine Corp., in Carson City, Nevada, for $350,000. And another engine design was sold earlier for even more.

“We’re looking at something right now,” says Rozanda Skalbania, “but we have confidentiality agreements so we can’t tell. I can say, however, we are negotiating, we have offers outstanding and there are some counter offers. Hopefully, something will be in place soon.”

If there isn’t, there’s no doubt that Norton soon will be nothing but a name in the record books and a logo on Tshirts. And won’t that be a shame.

Author Robert Zeller is a Canadian business writer based in London.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue