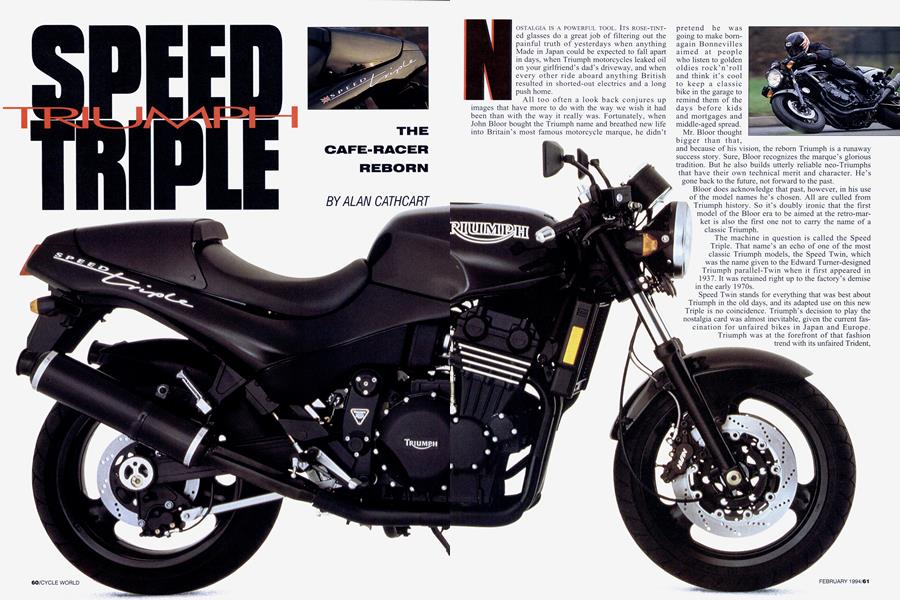

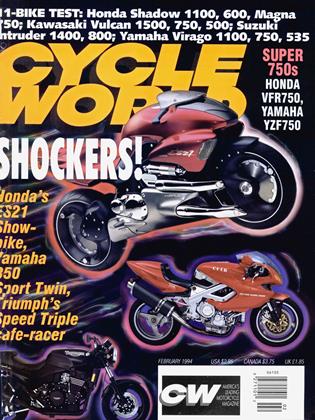

TRIUMPH SPEED TRIPLE

THE CAFE-RACER REBORN

ALAN CATHCART

NOSTALGIA IS A POWERFUL TOOL. ITS ROSE-TINTed glasses do a great job of filtering out the painful truth of yesterdays when anything Made in Japan could be expected to fall apart in days, when Triumph motorcycles leaked oil on your girlfriend's dad's driveway, and when every other ride aboard anything British resulted in shorted-out electrics and a long push home.

All too often a look back conjures up images that have more to do with the way we wish it had been than with the way it really was. Fortunately, when John Bloor bought the Triumph name and breathed new life into Britain’s most famous motorcycle marque, he didn’t

pretend he was going to make bornagain Bonnevilles aimed at people who listen to golden oldies rock’n’roll and think it’s cool to keep a classic bike in the garage to remind them of the days before kids and mortgages and middle-aged spread.

Mr. Bloor thought bigger than that,

and because of his vision, the reborn Triumph is a runaway success story. Sure, Bloor recognizes the marque’s glorious tradition. But he also builds utterly reliable neo-Triumphs that have their own technical merit and character. He’s gone back to the future, not forward to the past.

Bloor does acknowledge that past, however, in his use of the model names he’s chosen. All are culled from Triumph history. So it’s doubly ironic that the first model of the Bloor era to be aimed at the retro-market is also the first one not to carry the name of a classic Triumph.

The machine in question is called the Speed Triple. That name’s an echo of one of the most classic Triumph models, the Speed Twin, which was the name given to the Edward Turner-designed Triumph parallel-Twin when it first appeared in 1937. It was retained right up to the factory’s demise in the early 1970s.

Speed Twin stands for everything that was best about Triumph in the old days, and its adapted use on this new Triple is no coincidence. Triumph’s decision to play the nostalgia card was almost inevitable, given the current fascination for unfaired bikes in Japan and Europe. Triumph was at the forefront of that fashion trend with its unfaired Trident, but the appearance of the Ducati Monster a year ago, and its runaway commercial success, have changed all the rules. Now, Show doesn’t matter, if there isn’t also Go. That’s where the Speed Triple enters the picture.

Yet the Speed Triple is as different from a Monster as a ZX-7R is from a VFR750. This is not a style-conscious boulevard cruiser with performance potential. Instead, the Speed Triple is nothing less than a cafe-racer for the 1990s, a modem successor to those Tritons and Gold Stars and Dresdas that encapsulated the visceral thrill of ton-up two-wheeling a quarter-century ago.

Nothing I’ve ridden in years so perfectly captures the minimalist appeal of the cafe-racer concept. And in spite of having been developed around Triumph’s modular engineering approach, the Speed Triple is the most distinctive, hardedged and individual of the four models making up Triumph’s three-cylinder 750/900cc range.

The fact that there isn’t a 750 Speed Triple tells you this bike is about performance. Available only in 885cc form, the 900 Speed Triple was contrived by stripping a 900 Daytona of all its bodywork except the tank and seat. This foundation was then restyled and cloaked in black or yellow, your choice, with just a few subtle flashes of chrome. Orders are running 5 to 1 for the Black Beauty at present. Daytona wheels, brakes, suspension and exhaust system are fitted-the latter with carbon-lookalike black stainless-steel cladding to the twin silencers-to create a bike that has as much individual presence as, well, as a Ducati Monster.

But it’s very, very different to ride. Where the Monster is petite and Spartan, the Speed Triple is meaty and muscular, a hyperbike with performance dripping from every casting. Whereas the Monster is built as much to pose as to perform, the Speed Triple is built to accelerate hard, comer hard, run hard and stop hard. It’s the best-handling, best-stopping Triumph I’ve yet sampled, and the one you feel most closely a part of when you ride it.

The Speed Triple has 17inch wheels at both ends, and this testbike was shod with Michelin Hi-Sport tires, though Bridgestone Battlaxes also are approved footwear. And on these sticky tires-a 180/55 rear tire and a 120/70 front-the bike delivers superb traction, so it’s hard to resist the hooligan behavior invited by the Speed Triple’s stance. Thanks to a well-sorted Kayaba shock and to a fully adjustable 43mm fork that irons out minor road shock without diving excessively under braking, the suspension is just firm enough without being uncomfortable. This firmness, the bike’s grippy rubber and the sporting stance of the perfectly located clip-on handlebars permit you to probe the outer limits of the Speed Triple’s ground clearance. During my time aboard the bike, exploring that clearance resulted in a broken right footrest tab, a broken rear brake lever and a nerfed silencer. And that was with preload maxed up on the shock, which is adjustable only for preload and rebound damping.

The riding position is absolutely perfect, far more comfortable than that of the upright Trident at almost any speed, especially over 60 mph, where you no longer have to hang on for grim death to avoid being blown off the back.

Instead, you have a relaxing, wind-cheating riding stance against a pair of clip-ons wide enough to give good leverage for getting out of tight parking spots or for correcting slides when you’ve been overenthusiastic with the throttle. There’s a surprising amount of steering lock, too.

In spite of the bike’s very conservative 27 degrees of head angle, the steering isn’t as heavy as you might expect. This steering geometry actually works well with a bike like this, where you’re grateful for the stability around fast, sweeping turns.

The four-piston Daytona-spec Nissin calipers and their 12.2-inch discs worked really well. Triumph says the system is the same as on the Daytona I rode last year. The brakes on that bike didn’t exhibit the same feel or power. I suppose the Speed Triple’s 461-pound dry weight-about 10 pounds less than the Daytona-might be a factor, but I doubt it. I wonder if it’s not the extra leverage you get from the long lever fitted to match the clip-ons. I found myself gripping this nearer the balance-weight end rather than closer to the triple clamps. Hmmm. The white-faced instruments are neo-classically nice, if a little hard to read, except at night when a red glow illuminates them well. The single halogen headlamp is adequate without being searchlight-quality, and the little row of warning lights down the center of the dash on the 60s-style alloy plate is surprisingly legible, even in daylight. The bike’s rectangular mirrors give you a steady and wide rear view you’ll need if you use the bike the way it wants to be used.

However, all this is secondary to the Speed Triple’s trump card-that gorgeous, grunty three-cylinder engine with its unique exhaust note and counterbalanced smoothness. Hang on, though-where’s top gear? Someone at Triumph apparently decided that the 135 mph I saw on the Speed Triple’s white speedo was quite fast enough for an unfaired motorcycle, and told the engineers to leave out top gear from the sixspeed cluster. That was the only drivetrain change, however, right down to keeping the same 43-tooth rear sprocket used on the Daytona. Well, okay. The long-stroke Triumph motors (900 Triple and 1200 Four) don’t really need a sixspeed gearbox. They’re very torquey, and have superb throttle response. But it’s a mistake to have left the final-drive ratio the same as on the six-speed bikes. Even after some miles on the Speed Triple, you catch yourself still trying to shift into a non-existent sixth gear. An extra tooth or two off the rear sprocket would surely make the Speed Triple more long-legged without sacrificing acceleration excessively.

The engine has otherwise exactly the same specification as that of the Daytona 900, delivering a claimed 98 horse-

power at 9000 rpm, with maximum torque of 61.4 footpounds at 6500 rpm. It’ll pull cleanly from 1800 revs, but the glorious engine note you get in return for cracking it wide open at 4000 rpm-plus encourages you to ride the midrange torque curve, though the engine will run quite happily to the 9700-rpm rev limiter in all five gears.

Triumph plans to start Speed Triple production in February. Just 1400 examples will be built in 1994 out of a total production of 8500 machines. At £7600 (the equivalent of $11,325 at presstime) in Britain, which includes the 17.5percent value-added tax, expect Triumph to have the same sort of problem Ducati has with the Monster: making enough to satisfy demand.

So, it’s safe to stop thinking about the ghosts of Triumphs past. If this is the future, Britbike enthusiasts won’t need the past. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontWales Watching

February 1994 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsRushville Revisited

February 1994 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCGetting Started

February 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

February 1994 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Gts1ooo: Brilliant But Unsold

February 1994 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupHot Colors For A Cool Honda

February 1994 By Jon F. Thompson