PASO 906

Ducati introduces its engine for the `90s

ALAN CATHCART

THE 1988 COLOGNE SHOW WAS A LANDMARK FOR THE fortunes of Ducati and for those passionate about the company's motorcycles, but that significance went unnoticed by many show-goers. Almost everyone assumed the new 906 Paso, intro duced at the show, contained just a big-bore version of the venerable Pantah motor, introduced in 1977. You had to scrounge one of Ducati's scarce press kits to realize that all was not as it seemed; that here, in the most understated form conceivable, was the public launch of Ducati's basic power unit for the 1 990s-an all-new, two-valve, desmo dromic V-Twin with six-speed gearbox and full liquidcooling.

Designed from the ground up by Massimo Bordi, this engine owes nothing beyond its broad concept to the air cooled Pantah motor that was the last design of Bordi's illustrious predecessor, Fabio Taglioni. Indeed, there is scarcely a single component from the Pantah that will fit on the 906

Although some rabid Ducati fans will see the new en gine as an admission of defeat, an acknowledgement that the air-cooled engine couldn't be made to live within the hot confines of the Paso's all-enclosing bodywork, the 906 is actually a major element of Cagiva/Ducati's plans for at least the next decade. It is one of a family of three engines, all of which are now in production.

Explained Bordi, `A~ the lower end of the scale, we have the existing air-cooled Pantah engine, which will continue to be fitted to the entry-level 750 Sport for as long as it remains capable of homologation in a significant number of countries. At the other end, we have the watercooled 851 Eight-Valve desmo design, which, because its complication, can only be built in small quantities relatively high cost. In between, the majority of Ducati motorcycle production will be powered by the new 906 engine and its derivatives.”

Those derivatives include versions already under development for street use which employ a mixture of oiland air-cooling, for use in the dual-purpose Elefant, for example, as well as the fully liquid-cooled design fitted to the 906 Paso, which replaces the 750 model, now no longer in production.

In fact, the 906 Paso has been in production since the beginning of November and is already in the showrooms of Continental dealers, Bordi added. But it may be as late as 1990 before the 906 is sold in the U.S., in part because needs to be hushed down and cleaned up for American noise and emissions standards.

Bordi began work on the 906 before he began designs for the Eight-Valve engine, whose development was hurried along by the pace of Ducati’s involvement in Superbike racing. Thus the Eight-Valve engine appeared before the design it was, strictly speaking, derived from: the 906. The two engines share the same crankcases, six-speed gearbox, dry clutch and high-pressure liquid-cooling system. Apart from the altered stroke of the 906, the engines use the same crankshaft design, though instead of the 851’s Austrian-made H-shaped connecting rods, the 906 employs Ducati’s traditional ribbed conrod design.

PASO 906

The new two-valve engine’s bore and stroke measurements are 92 x 68mm, compared to the 85 l's 92 x 64mm, giving it a capacity of 904cc. So why call it the 906?

“Do you want the real answer, or the public relations rationale?” asked Bordi. “The real reason is that the 906 logo on the fairing is symmetrical, so I like it better. The official excuse, which I thought up later, is that it's a 900 with a six-speed gearbox.”

Running on 9.2:1 compression and unleaded fuel, the 906 engine is a blast from the past fit for the future-like a version of a '60s hit record revamped so completely by one of today’s bands that it sounds fresh and new. I can't pretend that my quick ride on one of the first production bikes straight off the factory floor qualified as more than a brief introduction, but in just a few miles I realized what I was riding: a bike powered by the 1990s’ version of a 900 Big Twin, the engine that many traditionalists revere as the last real Ducati motor, mainly because of its bevel-drive valve gear.

The 906 has the low-down grunt and smooth torque of the old engine that the higher-revving Pantah never fully enjoyed, but those characteristics are offered in a quieter, less raw-edged package than the engine oí five years ago. That may be a drawback in the books of some ducutisti. but the fact is that the world has changed, and with ever-morestringent rules on noise and emissions, and it simply isn't realistic to expect anyone to market a 900SS anymore.

The 906 pulls from practically zero-with strong torque as low as 2000 rpm-up to the nine-grand redline, with claimed horsepower of 74 bhp at the rear wheel (88 bhp at the crank), delivered at 8000 rpm. This ultra-wide powerband, exceptional even by Ducati standards, is due mainly to Bordi’s top-end design. It is based on Pantah principles with the same 60-degree valve angle, but with a completely new “triple-hemisphere” combustion chamber design, flat semi-slipper pistons and large inlet and exhaust valves.

Big valves often lead to an engine that doesn't run well down low. but thanks in part to the Marelli digital ignition, the 906 has a remarkably tractable engine. The same twinchoke 44mm Weber carb is fitted to the 906 as on the 750 Paso, but the massive flat-spot embarrassingly and incurably present on most Pasos appears to have been eliminated. The bike I rode was picked at random off the production line, so either there’s at least one lucky owner or Ducati really has licked the problem.

With its new engine, the 906 Paso should knock off 12second quarter-miles, and a prototype has already been clocked at 136 miles an hour. The performance gains come in spite of the inevitable weight penalty of the bike’s liquid-cooled engine. It scales 159 pounds complete with carb, and brings the claimed dry weight of the complete bike to 452 pounds, compared to the air-cooled 750 Paso’s claimed 430 pounds.

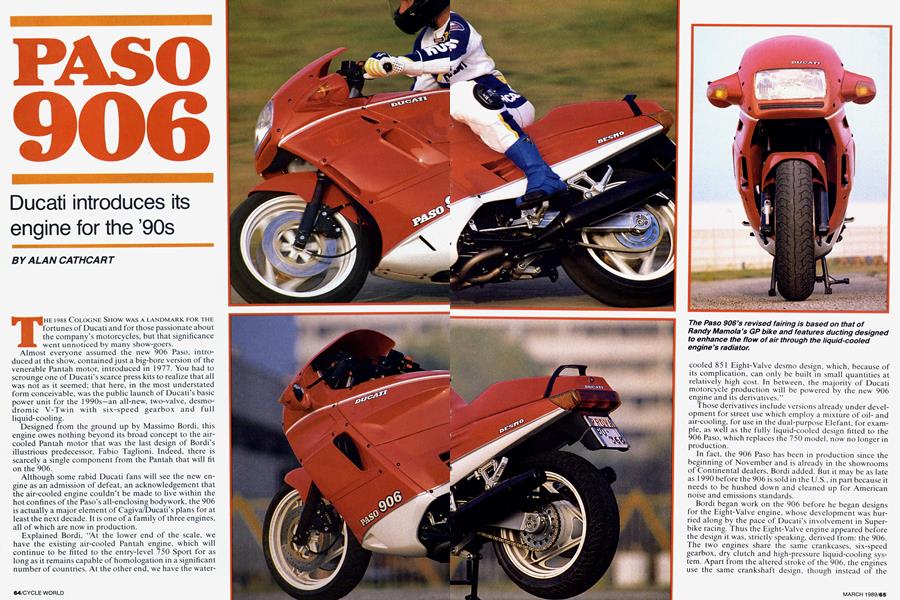

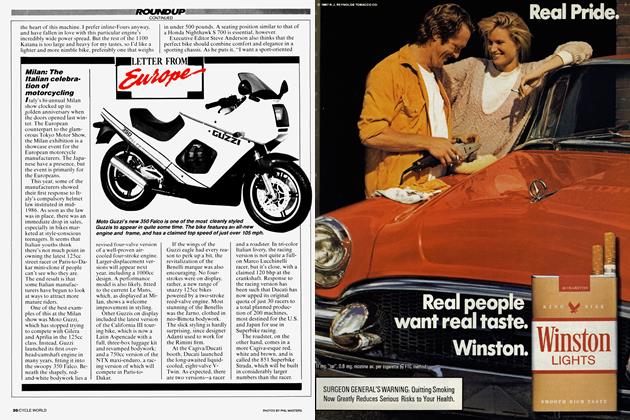

Comparison of the two versions of the Paso is appropriate because the 906 uses the essentially the same chassis and components as the 750. with some modifications. The most obvious change is the white base to the red bodywork, which has the effect of lightening the bike’s previous, rather-bulbous appearance. There are also some revisions to the fairing, which now incorporates ducting both in the sides and internally to achieve maximum flow of cool air into the radiator and hot air away from it, and is based on the bodywork designed by Massimo Tamburini for Randy Mamola’s 500cc GP Cagiva.

The only major change to the 906’s chassis from that of the 750 is its front suspension. The same 42mm Marzocchi fork is used, but its travel has been reduced slightly, presumably to curtail the front fender from contacting the bodywork during full-on stops, a problem that plagued some 750 Pasos. Additionally, the steering-head angle has been kicked out a degree to 25 and the trail also increased, all to offer more-stable handling.

Certainly the 906 seems to handle in a more relaxed and predictable way, especially under braking, than the 750 Paso. But the 906, like the 750, is equipped with 16-inch wheels and still sits up on you if you try braking when it’s cranked over, if a bit less than before. Bordi recognizes the problem and claims that until 17-inch wheels can be fitted to the 906, new-generation Pirelli radiais, expected shortly, which have a different, less rounded profile than the present design, will resolve the problem. I hope so, especially as the trait spoils enjoyment of what is otherwise light and confident steering.

While Bordi's at it, I hope he increases the size of the front discs and replaces the ancient twin-piston Brembo calipers. These items work well in average use, but from experience with them on the 851, I don’t think they’ll be powerful enough at the sort of speeds owners of the heavier 906 are likely to attain.

Though the Paso doesn't excite me in the way that the elemental 750 Sport does, I must admit Bordi has succeeded in producing an engine that meets all the requirements of the 1990s in an engineering sense, while still retaining the lusty nature and lilting, offbeat grunt of a traditional Ducati V-Twin. Because of that engine, the 906 is a rider’s delight, likely to become as much of a classic in its own time as the 900SS and the Pantah were in theirs, yet accessible and acceptable to a far wider range of customers than the trick, expensive 85 1 Eight-Valve.

So, rather than being an admission of defeat, the 906 is instead a declaration for the future. And it’s right the first time: Half a decade after the last bevel-drive Ducati was made, the Big Twin is back.