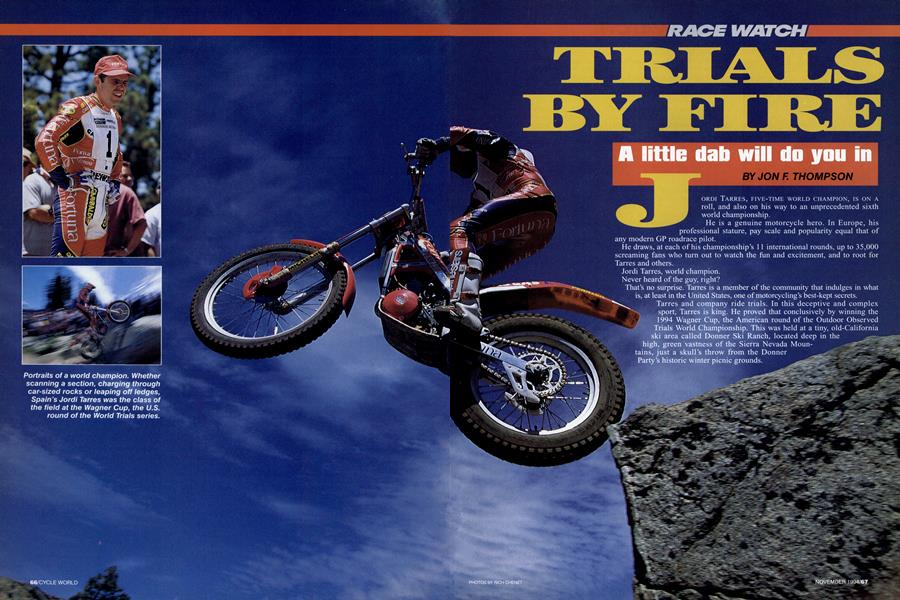

Portraits of a world champion. Whether scanning a section, charging through car-sized rocks or leaping off ledges, Spain’s Jordi Tarres was the class of the field at the Wagner Cup, the U.S. round of the World Trials series.

TRIALS BY FIRE

RACE WATCH

A little dab will do you in

JON F. THOMPSON

JORDI TARRES, FIVE-TIME WORLD CHAMPION, IS ON A roll, and also on his way to an unprecedented sixth world championship.

He is a genuine motorcycle hero. In Europe, his professional stature, pay scale and popularity equal that of any modern GP roadrace pilot.

He draws, at each of his championship’s 11 international rounds, up to 35,000 screaming fans who turn out to watch the fun and excitement, and to root for Tarres and others.

Jordi Tarres, world champion.

Never heard of the guy, right?

That’s no surprise. Tarres is a member of the community that indulges in what is, at least in the United States, one of motorcycling’s best-kept secrets.

Tarres and company ride trials. In this deceptive and complex sport, Tarres is king. He proved that conclusively by winning the 1994 Wagner Cup, the American round of the Outdoor Observed Trials World Championship. This was held at a tiny, old-California ski area called Donner Ski Ranch, located deep in the high, green vastness of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, just a skull’s throw from the Donner Party’s historic winter picnic grounds.

Tarres and 13 other European trials riders who showed up fresh from the French championship round to compete against each other, and against nine U.S. and Canadian riders, no doubt wondered where the hell everybody was. On the Saturday and Sunday of the two-day event, about 2500 souls—a big gate for an American trials event—showed up on Donner Summit to watch the fun. Those lucky enough to be part of that gate this hot, dry June weekend witnessed an amazing display of motorcycle virtuosity.

Except for the rapidly growing European extravaganza known as stadium trials (see “Over the Top,” Cycle World, August, 1993), trials events are held on natural terrain. Trials riders challenge traction on dirt, rock, grass, mud and water. But the single biggest difference between trials and other events such as motocross and roadracing involves scoring procedures. In MX and roadracing, to win, all you have to do is beat the other guy to the finish line. In trials, you also have to beat the other guy, but it’s nowhere near as simple as merely being the first rider across the finish line.

This round of the world championship, the seventh of 11, consists of a 3.5-mile loop broken down into 12 sections-jumbled rockslides and sheer mountainsides carrying ominous names like “Elevator,” and “Roller Derby.” A rider must navigate his machine over each section without dabbing-touching his foot to the ground. Dab, get a point.

Everyone dabs. He who dabs the least, wins.

It’s that simple, and yet it isn’t. The truth is, you can dab all you want. The maximum number of dab points a rider can get on a section is three. If, however, a rider comes off his bike, goes out of the section boundary, rolls backwards while a foot is down or commits other sins, he “fives.” That means he is given five points for that section, the highest score possible. Five a section-yes, five isn’t usually a verb, but in trials it is-and you may as well skip the rest of it. Complicating this is a rule requiring that each section be completed in three minutes or less. Every minute more than that results in a point added to the rider’s section score.

Back in the dim days of history, a trials bike was just a roadbike stripped for dirt use. But not now. Now, a trials bike-they go by names like Fantic, Gas Gas, Montesa, Beta and Scorpa-is a tiny and very specialized thing. It has no real seat, since it was built to be ridden from its footpegs. Its liquid-cooled, twostroke, single-cylinder engine displaces 250cc and makes maybe 30 horsepower. Its transmission has six speeds. The three bottom ratios are all very low, and are all very close to each other, with a bit of a jump to fourth, and fifth and sixth so high that they’re used-if they’re used at all-only for getting between distant sections. Fuel tanks, tucked down between hefty aluminum frame spars, hold a gallon of premix. Wet, the bikes weigh as little as 170 pounds. Lots of suspension travel, though not as much as on most MX bikes, is typical with lots of spring, a bit of compression damping, and not a lot of rebound damping. Traction, and the maintenance of it, is all-important, so to maximize grip over highly suspect riding surfaces, there’s maybe 4 or 5 pounds of pressure in the rear tubeless radial knobby and perhaps a half> pound more in the front, which is a bias-ply tube tire.

Explains Mike Fenner, a member of PITS-the Pacific International Trials Society, this event’s hosting club“These riders hit the obstacles so hard with the front tire, it will knock a tubeless tire loose from the rim,” clearly a circumstance to be avoided.

Trials sections are so rugged that they cannot be walked over. One must climb, using hands as well as feet. So rugged are they that some obstaclesthe 12-foot, barely-angled rock face that begins Section 8, for instancewould defeat the ordinary hiker. He’d go around. The trials competitors find a way to scrabble to the top.

Some, in fact, disturbed by the amount of rock here and the resulting lack of opportunity to demonstrate their traction control on truly slippery surfaces, make wry comments about the Donner Summit course. Says Tarres diplomatically, “The course is very good, but it is a little bit easy. It is spectacular, but with very much grip.”

Easy or not, watching the riders as they negotiate a section is a study not only in the defiance of gravity, but in grace, fitness and athleticism.

A rider begins each section in the start area, at rest, but feet up and balancing, blipping his bike’s throttle, clutch in, nervously shifting up and down, up and down. Riders start a minute apart, and they negotiate each section one at a time. At the sound of the whistle or horn that marks the beginning of his three minutes, the rider settles into second or third gear, and releases his clutch. What follows is a subtle explosion of energy as the rider uses his entire body to will his bike over obstacles that look impossible.

Norm Sayler, owner of Donner Ski Ranch and a trials enthusiast and instructor, explains how it’s done: “At any given time the rider is putting pressure on one footpeg or another, he’s steering and pulling up or pushing down on the handlebar, he’s bending, in multiple directions, at the toes, ankles, knees, waist, shoulders, elbows, wrists and neck, he’s using the front and rear brake, the clutch and the throttle, sometimes all at the same time. It isn’t easy.”

No, and to see how it’s done, there’s no better group of riders to watch than this one, a United Nations of riders, men like Tarres, Joan Pons (like Tarres, from Spain); Finland’s Tommi Ahvala; Italy’s Donato Miglio; Japan’s Takumi Narita; and England’s >

Dougie Lampkin. When they’re on and lucky, they make even the most difficult sections look easy. To “clean” the sections-that is, make it through without gathering any points-they ride the wheels off their bikes, making haste slowly; flying, quite literally, over obstacles by harnessing the power stored in their bikes’ engines and springs and in their own brains and muscles.

Saturday, the riders do the first of three loops. This is the equivalent of a sighting lap, in which the riders, forbidden from practicing on the sections, get their first looks at them. They take their time, walk each section, study each rock, each climb, each step, each crevasse. It takes them six hours to do the first loop. When it’s done, Tarres and Pons, both Gas Gas-mounted, are tied for the lead, Tarres with points in five sections, Pons with points in just two-he’s fived in Section 7, and dabbed in another. Section 7 will prove to be every rider’s nemesis at this event; almost everybody fives here. The problem is a stone step, so perfectly, hugely square that it might have been cut by stone masons to fit seven-league boots. It’s 6 foot, 6 inches high. One knowledgeable

viewer says, “It’s impossible. Maybe.” For most, it is impossible. Those that come closest to making it are rewarded with huge cheers and applause from spectators knotted around this toughest of obstacles. Brit Steve Colley, who ultimately finishes fourth, is, with Tarres, one of the few who doesn’t five here. Tarres and Colley both dab, but each makes it. Each uses a similar technique. He attacks on an angle, pins the throttle, modulates the clutch, lifts the front end, rebounds off the rear suspension, and using the handlebar combined with muscleand spring-power, lifts his tiny bike so that its rear tire just barely catches the edge of the step, a kiss of sticky rubber on granite. With the help of a strong dab, each makes it.

Other obstacles are handled differently. The bikes jump from rock to rock, for instance, leaping from a standstill and landing with the front brake locked on, so that the bike stops right where it lands, sometimes in a nose wheelie so the rider can kick the chassis around in a very stylish direction change.

If Saturday’s loop is the sighting lap-even though scores are kept by the section judges-Sunday is raceday. Things are serious, because today each rider will do two loops. To make things interesting, he not only will traverse each section in three minutes,

he also has to complete both loops, all 24 sections, within five hours.

After lots of work, sweat, panting and bruised shins, knees and elbows, all of them do, though there is a huge gap between first and last. Tarres finishes with 18 points, his low score a measure of his mastery over his sport. Pons is second, with 26. Ahvala also gets 26, but his Saturday loop wasn’t as good as Pons’. That’s used as a tiebreaker, and Ahvala’s Saturday performance relegates him to third. Dougie Lampkin, coached by his father Martin, world champion in 1973 and 1975, is 10th, with 45 points. This comes in spite of a bone-jarring get-off crossing a huge log in Sunday’s final section. Top American is Beta-mounted Geoff Aaron, with 108 points. Last-place rider, young John Clark, has 176.

Their scores do not in any way diminish what both Aaron and Clark accomplished here. While most of the rest of America was at home watching televised sports, Aaron and Clark were involved in world-championship competition, dueling with the very best.

They do it for love of the sport, for there is no prize money involved. Tarres may make $2 million in sponsorship and appearance money, and the next top-five riders $250,000 each per year, but for the Americans, this is a labor of love. Except it isn’t exactly labor. Here at 7000 feet in the cedar and pine of the Sierra, under the deepspace-blue skies of a perfect June day, these men all are motorcycle competitors, and there isn’t any place they’d rather be. Feet up, they’re going for it. They’ll go for it again.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

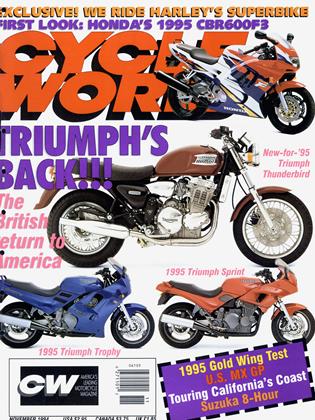

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontIncident On the Angeles Crest

November 1994 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsGs-Ing It

November 1994 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCEngine Architecture

November 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1994 -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia Reveals Trick 250

November 1994 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki Gets Savage For 1995

November 1994