TDC

Doing it

Kevin Cameron

Now AND THEN I GET A CALL FROM someone who is clearly appealing to me for courage.

“Look,” the voice says, “I’ve got an old R5 Yamaha that I race in vintage, and I’ve been thinking of changing the crank....”

The voice trails off indecisively, so I supply the missing word, “Yourself?”

“Yes.” He gains strength. “I’ve bought a service manual, but I’m not sure I should tackle a job like this on my own.”

I remember this predicament well. What if I do everything the manual says and it still won’t start? What if I have parts left over? What if I do my best and it’s an embarrassing flopperoo? What if everybody laughs and points?

So I muster my best uncle voice and reply, “Do it. A simple engine like that only goes together one way, and you have the manual to make sure of that.”

There’s relief in his voice. I’ve given the answer he hoped to hear. Getting through this first job, I continue, will open lots of doors, and you’ll never have to fear the mysteries of engines again. The fear of making a catastrophic mistake will be countered by seeing first-hand what is and what is not very important in assembling an engine. All that scary, unknown stuff-crankshafts, bearing locating rings, gears, shift forks—will soon be old hat, comfortable. Step by step, with case sealer sticking your fingers together, you will be initiated.

I was in this very predicament when I bought my first computer in 1986. Inside the box were unseen and mysterious innards that turned my keystrokes into hard copy squeaking out of the printer. Then it quit. I was stunned. I called the faraway dealer.

“Uh, you got a screwdriver?” he asked me. I admitted that I did have one. “Well, just take the cover off and you’ll find a bunch of connectors in there. When they ship these things, the connectors work loose. Just try pushing them back together and see if the computer works then.” His voice was dry, matter-of-fact. Do this and get results.

I took out the screws and removed the top. Inside were neither gods nor demons-just a bunch of parts. As promised, one of the connectors was loose. I squeezed it together. The computer worked again.

Unfortunately, our world is quickly becoming one big black box labeled, “Warning. No user-serviceable components inside.” This is quite a change in a hundred years. In my great-granddad’s time, a man had to be able to build a house or barn, fix broken farm machines, deliver his own children and set a broken bone. Today, my wife notes, the trend among men is to have skills in only two areas: one is what they do at work; the other is watching sports. This kind of narrow specialization may work in our black-box world, but it also imprisons us behind high thresholds of ignorance. Better not try to do anything because it might come out wrong. Leave it to the experts. Call a man. Sit tight. Watch more TV My uncle initiated me to the internal combustion engine in the summer of 1954. “We’ll overhaul that lawnmower engine,” he told me. “It’s getting weak.” Adventure! We tore down the engine, revealing its mysteries. Then we found the Briggs & Stratton dealer, found part numbers for gaskets and piston rings, and came home with our goodies. We scraped off old gaskets, we ground valves, we de-carboned piston-ring grooves. Then we cleaned everything up and reassembled, with fresh oil. With my father standing to one side, cheerfully offering that the engine would never run again, we filled the gas tank and reached for the starting rope. Pack! It fired on the first pull, then started and ran. It was delightful, and I’ve never quite recovered from that pleasure.

Just perform the steps described in the manual (or stored in your own head) and engines will obey you. Mysteries decoded by mortals.

That uncle returned another summer to rebuild his car engine, a StraightEight Buick. He showed me how to punch out holes in cardboard to keep valves and pushrods in order. We scraped sludge. We scoured the town for parts. Once the last bolts were tightened, he eased into the red leather seat and casually started the engine. Nothing to it-provided that the critical things like piston-ring fit and bolt torques were right.

This is not to say that the “initiated” never get it wrong; mechanics, like politicians, can make mistakes from time to time. It’s humbling to go to Daytona with your new racebike, thinking yourself competent, only to find that you’ve installed first gear backward so it can’t be engaged. There was no one but myself to blame. I did the job over again, resolving inwardly to be more careful, to perform all the necessary checks, to do it right next time. Each experience of your own limits and capacity to make mistakes creates a stronger determination to think the next job through clearly and without distraction. You accumulate little tricks along the way that make your work easier and surer. You know what you’ll need ahead of time, and line up the “ingredients” just as a good cook does.

For the person tempted to take up tools to understand machines from the inside, the first job can be a nail-biter, but to get through it and be rewarded with a running engine is sweet. A modicum of determination, some appropriate tools, a service book or an indulgent (and knowledgeable) uncle, and you’re on your way.

In the hands of an experienced mechanic, working under time pressure, the crank in an older Yamaha Twin like the caller’s R5 can be changed in about an hour-it was routinely done that quickly at the races. But to reach that level of competence and assurance, the beginning mechanic must first push through the barrier between timid ignorance and initiated knowledge. It’s a valuable crossing to make, because it’s a model for all the other doors in life that can be opened by the same process.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

August 1994 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

August 1994 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1994 -

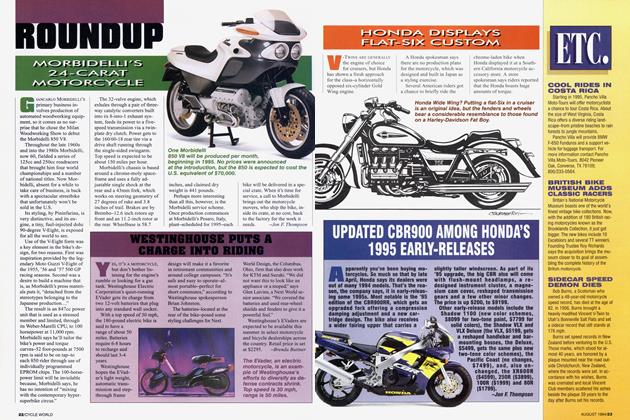

Roundup

RoundupMorbidelli's 24-Carat Motorcycle

August 1994 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupWestinghouse Puts A Charge Into Riding

August 1994 By Brenda Buttner -

Roundup

RoundupHonda Displays Flat-Six Custom

August 1994