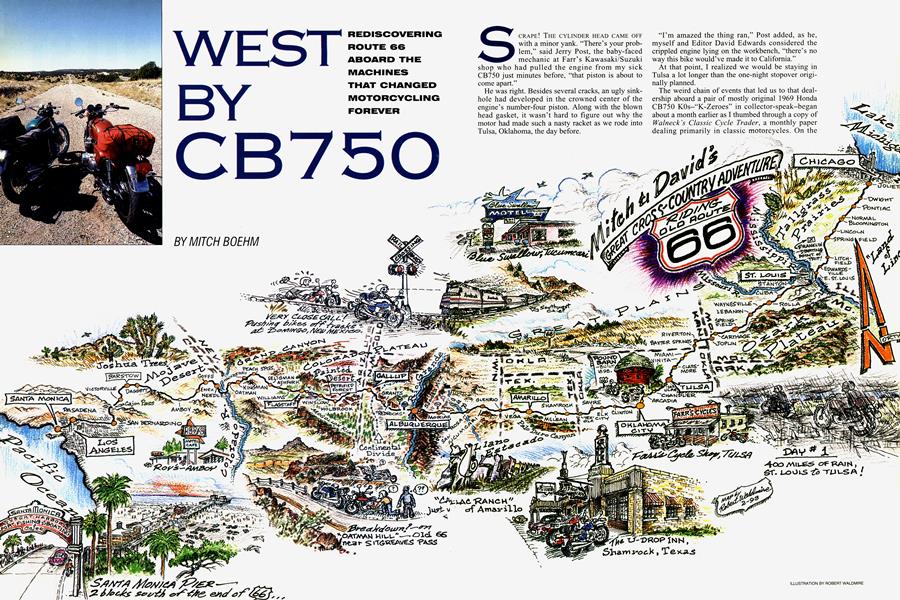

WEST BY CB750

REDISCOVERING ROUTE 66 ABOARD THE MACHINES THAT CHANGED MOTORCYCLING FOREVER

MITCH BOEHM

SCRAPE! THE CYLINDER HEAD CAME OFF with a minor yank. “There’s your problem,” said Jerry Post, the baby-faced mechanic at Farr’s Kawasaki/Suzuki shop who had pulled the engine from my sick CB750 just minutes before, “that piston is about to come apart.”

He was right. Besides several cracks, an ugly sinkhole had developed in the crowned center of the engine’s number-four piston. Along with the blown head gasket, it wasn’t hard to figure out why the motor had made such a nasty racket as we rode into Tulsa, Oklahoma, the day before.

“I’m amazed the thing ran,” Post added, as he, myself and Editor David Edwards considered the crippled engine lying on the workbench, “there’s no way this bike would’ve made it to California.”

At that point, I realized we would be staying in Tulsa a lot longer than the one-night stopover originally planned.

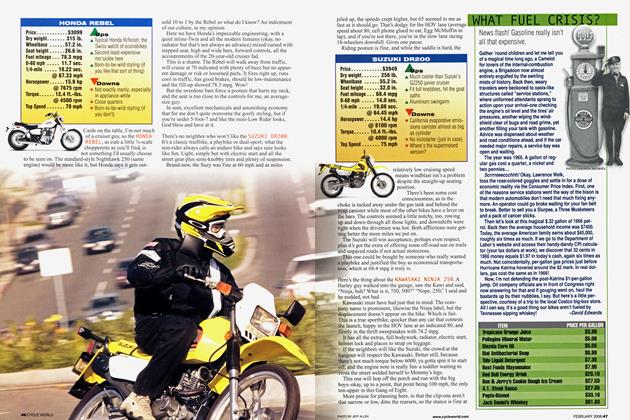

The weird chain of events that led us to that dealership aboard a pair of mostly original 1969 Honda CB750 KOs-“K-Zeroes” in collector-speak-began about a month earlier as I thumbed through a copy of Walneck’s Classic Cycle Trader, a monthly paper dealing primarily in classic motorcycles. On the next-to-last page, just below a grainy black-and-white photo of a pair of bikes sitting in a field, I spied an ad that read: “(2) 1969 Honda CB750s. 1 red, 1 blue. Both original and nice. Trades or offers.”

I had always dreamed of owning a first-year CB750, even back in the early ’70s in northern Ohio, where I spent the majority of my youth tearing up the fields behind our house aboard my very first motorcycle, a fire-engine-red Honda SL70. A guy who lived at the end of our street had an aqua-blue 750 Honda, and every day he would roar past our house on his way to and from work, the crisp, almost magical wail of those four exhaust pipes ricocheting through the neighborhood. The image of that bike and the sounds it made were powerful stuff for a 10-year-old just discovering motorcycling, and they had stayed with me since.

The ad had been placed by a Mr. Thomas L. Smith, who made his home in southeastern Illinois, about 90 miles north of St. Louis. I remember thinking that Illinois was a long way to go to buy any motorcycle, let alone a sight-unseen one, but after all, this was a pair of honest-to-goodness ’69 CB750s in supposedly good shape, an intriguing find. So I yelled into the next office. “Hey David,” I said, “you wanna buy a ’69 Honda 750?”

Now, Edwards can’t get enough old, neat motorcycles, but since he’s already got a half-dozen or so classics cluttering up the Cycle World garage, I expected little interest from him. Big surprise. Sixty seconds later we’re hunched over his desk, scheming away like a couple of 12-year-olds in a tree fort. “Here’s what we’ll do,” he said, “we’ll fly back there, buy the bikes, and ride ’em home on Route 66. It’ll make a good story: I’ll shoot the photos and you can write it.”

After some dickering, Smith said he would take $4000 for the bikes, a lot of money for a couple of unproven 23-yearold Hondas, especially considering the state of my bank account, but the plan-foolish and irresponsible as it was-had its appeals. After all, this wasn’t simply a chance to traverse Route 66, the most renowned two-laner in America, the road John Steinbeck called “the mother road, the road of flight” in his epic novel The Grapes of Wrath; here was a chance to secure for my garage the very machine that helped ignite my lifelong attraction to motorcycling, a bike I’d lusted after since I was a kid. Heck, this was perhaps the most important Japanese motorcycle ever made.

And there was more. Unlike a typical cross-country trek, this excursion would give us the chance to tour The Way Folks Used To Tour, back in the days before full fairings, air suspension and four-speaker audio systems. Financial chaos or not, I was all for it. David would get the aqua-blue bike; I’d get the red one, which would go perfectly with my candy-red 1979 CBX Six.

Three weeks later, cash in our pockets and an absolute minimum of riding gear in our Rev Pak bags, we boarded a Boeing 757 bound for the St. Louis, Missouri, airport, where Smith had agreed to pick us up. Somewhere over eastern New Mexico, I wondered for the 20th time what condition the bikes would actually be in: Would they be as mechanically sound as their owner thought they were? Or were they actually worn-out heaps that would strand us in the middle of the Texas Panhandle, which, from my vantage point at 35,000 feet, looked mighty desolate.

When we got both bikes running later that day in Smith’s garage, I felt better about the whole deal, though it was clear to me that we weren’t dealing with particularly well-maintained machinery here. Besides needing a healthy amount of coaxing before it would fire, my candy-red 750 sounded noisy and loose, as if it had twice as many miles as the 24,000 showing on its clock. It had also been repainted, which did little for my disposition, since I’d been told that its paint was original. David’s aqua-blue 750, with about half as many miles, sounded much tighter and looked significantly better, though neither machine appeared eager to deal with a journey of the magnitude we had planned, even after mounting the new tires and seats we had sent ahead from California.

After saddling up the bikes, we waved goodbye to the Smith family and headed south toward St. Louis and the point where we’d pick up 66. Our goal that chilly evening was to ride the 90 miles to St. Louis, find rooms, and pray for good weather and reliable motorcycles the following day, when we planned to get as far as Tulsa, Oklahoma, roughly 400 miles to the west. As we headed through the endless cornfields of southern Illinois, I felt what must have been the same mixture of excitement and apprehension the members of Steinbeck’s Joad family must have felt as they embarked on their westward journey from the Oklahoma dust bowl of the 1930s.

Our prayers for clear weather and trouble-free mounts obviously went unanswered, because we were greeted with foul weather and flawed motorcycles the following day. The steady rain and 40-degree temperatures weren’t so terrible-we’d brought electric vests and rain gear-though the oil pumping from the breather systems of both engines was. Within a hundred miles, oil had covered our luggage and the rear tires of both bikes. Add that to the pouring rain, the frigid temperatures and the growing metal-to-metal clatter coming from my bike’s engine, and you get a pretty good idea what our 10-hour ride to Tulsa on Day One was like.

Our luck changed the following morning, however, through a chance encounter with a gentleman named Jerry Burrell, who we met at a gas station and who led us to the only dealership within 200 miles that was open on Mondays, a Suzuki/Kawasaki shop owned by Funnybike drag-racer Marshall Farr and his wife Vicky. Burrell told us that the folks at Farr’s were not only good people, but good with the wrenches, too.

He wasn’t kidding. Especially young Jerry Post, who turned out to be a veritable CB750 wizard who had rebuilt dozens of single-cam 750s as a teenager. As it turned out, David’s bike had wrongly routed oil-breather lines-a relatively easy fix for Post. He even routed additional lengths of breather hose out past the rear fender, old-Triumph style, just in case the oiling problem came back

My bike, however, was far more seriously flawed. A previous owner had done a particularly miserable job of installing a big-bore kit; the engine was also so worn that combustion pressure was blowing past the rings, pressurizing the crankcase and pumping oil out of the breather tubes. The bike’s top end was a mess, and only after scouring the Tulsa area for a new cylinder and a set of pistons and rings were we able to finally get my bike running right. After two-anda-half days, we were on our way. Again.

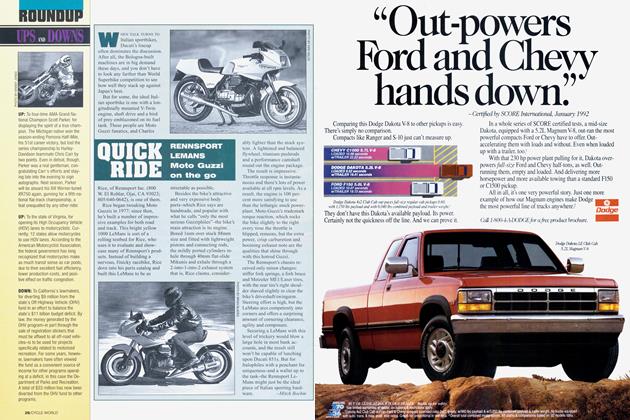

Up to that point, we’d seen little of legendary 66. But as we rode westward from Tulsa, through small towns with names like Sapulpa and Chandler, the 66 I’d read about and began to come alive. These were small, country hamlets, each, it seemed, with a filling station, a church and a Main Street lined with cafés and antique shops. At one point, we rode past a deserted high-school football field with faded wooden bleachers and tall light poles surrounding the field. I closed my eyes and could picture the scene on a Friday night: The packed grandstands, the brisk night air filled with the sound of cheering and the smell of hot dogs and freshly mowed grass. Just like back home in Ohio. Like

the towns it cut through, the road itself radiated char96/CYCLE acter and history. As we rode along, the bikes now running smoothly and crisply, and dripping only a bit of oil, we noted older, original sections of 66 branching off from the main route. These were usually short loops through the woods, or sections that ran parallel to the newer route, with weeds growing though the cracks. Not all of these sections were asphalt; some were concrete, laid down in sections like rows of dominoes. Over the years, the climate and traffic had broken the surface, which made both bikes, with their worn, underdamped legs, bounce around a lot.

What must it have been like to travel this road back in the ’30s and ’40s? Buddy Marion, an older gentleman who is a fixture at Farr’s shop, recalled his travels on 66 as a kid in the ’30s. “Back then,” he said, “66 was the only way to get to Oklahoma City, or anywhere else west. Going to OK City [roughly 100 miles away] was a big deal back then. My dad would spend a whole day checking over the car, a ’38 Ford, I think it was.”

We stopped for lunch at the Sweets’n Eats Cafe in Stroud, Oklahoma, which featured a recently restored, vintage Coke sign painted on the side of the 88-year-old building. Elmer and Peggy Williams owned the place; Peggy cooked, and, if you were willing to listen, Elmer told stories. “Back then, the road was mostly sand and gravel,” he told me. “I went west on 66 in 1936; musta had 40 flats on that trip, and we broke an axle somewhere in Texas.”

Despite the cozy towns and the neighborly people along the old route these days, it was tough to ignore the decay that had taken place along its path over the years, especially as we drove westward into the flat, dry desert of Texas. In towns like Texola and Shamrock, homes and businesses were boarded up by the dozens. It was eerie; each of these abandoned filling stations, tourist courts and cafés were once-thriving businesses, healthy enterprises that represented someone’s hard work and dreams, a future for their family. Now, they were no more than faded, crumbling ruins, homes for rats and birds and drifters.

People we talked to along the route were bitter about the decline. These folks missed the Old Days, when business and life in general along 66 was better. In Grants, New Mexico, a uranium-mining boom town that flourished until Reagan-era deregulation cut the guts out of the U.S. uranium business, we met up with Pete Chandis, the son of Greek immigrants, who had come to Grants back in ’55 and operated a café called the Western Host Restaurant. In those days, Chandis, now 71, was open 19 hours a day, employed a dozen people, and had a line of people waiting impatiently at the door when he’d open up every morning. Now it was just him: host, waiter, cook and cashier.

“Those were the good old days,” he said, as David and I ate the breakfast Chandis had just cooked for us, “I was open 5 a.m. to midnight every day.” I asked him what had happened. “The interstate killed us,” he said, looking at the dusty tables cluttering the dining room, “the day 1-40 opened, it was like an atomic bomb hit this town.”

One of Chandis’ few regular customers, Colonel Bill Loughnane, a sharp, West Point grad in his 70s who had flown P-47 Thunderbolts in WWII, F-86 Sabres in Korea and F-4 Phantoms in Vietnam, agreed. “Eisenhower’s buddies didn’t make enough on the war,” he said, “so he had them build the interstates.” Breakfast finished, we gave Chandis a big tip, thanked him and the Colonel for the conversation, and walked out to the bikes. As we saddled up, I couldn’t help but smile at the sign in front of the café. It said: “Yoo-Hoo...Eat here, or we both starve. 34 years. Breakfast always.” Like the road he lived his life on, Pete Chandis was a survivor.

In a way, our bikes were survivors, too. Like 66, the golden years of the mighty CB750 have been decades past, but these first-year bikes had stood up pretty well over time despite the mechanical gremlins we had uncovered. Just as Pete still made a pretty good bacon-and-egg breakfast, these bikes could still get you from point A to point B in comfort and style, and do so with enough power and handling ability to keep things interesting. They weren’t overly fast, they had flimsy brakes and a loose, distinctly “old bike” feel, but considering their age and the low-maintenance life they’d led, they worked surprisingly well.

Heading west, though, we couldn’t quite steer clear of mischief. Just out of Santa Fe, New Mexico, we stopped at the Santo Domingo Trading Post, a neat little mercantile that had attracted the likes of John F. Kennedy and the editors of Life magazine to its doors in the early ’60s. The bikes looked particularly brilliant basking in the golden, afternoon sun, so we rolled them onto the train tracks just in front of the trading post to take a photo or two.

Out of nowhere, an Amtrak train came barreling around a bend in the tracks at about 80 mph. Caught completely off guard by both the appearance and speed of the train, we sprinted the 30 or 40 feet to the bikes, pushed them off their centerstands and rolled them off the tracks. We got them out of harm’s way maybe five or six seconds before the train thundered by, and the adrenalin that flooded my gut damn near made me throw up. We ran into more bum luck just out of Oatman, Arizona, an old mining town that once housed Clark Gable and Carol Lombard for the night on their honeymoon. On a steep, switchback grade, David’s drive chain threw its masterlink, which allowed the chain to wad up against the engine case and knock out a hole large enough to give a clear view of the transmission gears-not an uncommon occurance with early Honda 750s. We temporarily fixed the hole later that evening after limping back to Kingman, using a scrap of aluminum and some amazing metal epoxy called JB Weld.

The wildest part of the Oatman breakdown was the appearance of Cajun and Wanda-a beer-drinking, outlaw couple who rode up on a Harley Softail and stopped to help. Attached to a buckle on his right boot, Cajun just happened to have a correctly sized master link, which he agreed to sell us. As Wanda pulled a Budweiser from one of the Harley’s leather bags, Cajun grabbed the $10 bill from David’s hand and drawled, “You guys are lucky; we usually don’t stop for Jap bikes.” Ironically, we’d brought extra master links for just such an emergency, though they had been machined incorrectly and didn’t fit.

Two days later, after crossing the California desert through Needles, Amboy, Barstow and Victorville, we started down the Cajon Pass, which would funnel us into the Los Angeles basin. Heading down the grade, we rode a neat old section of original 66, which paralleled the freeway yet rarely saw traffic. Then, just before it dumped us into smoggy San Bernardino, Route 66 suddenly dead-ended.

David and I stopped, killed the engines, and just sat there, staring off past the barricade. The original path of old 66 went another 75 miles, all the way to Santa Monica and the Pacific Ocean. Very little is left today, and neither of us had much enthusiasm for finding it. For us the real end of 66-The Mother Road-was here; ending this inspiring trek on the crowded and dirty streets of L.A. would be somehow sacrilegious.

As I sat there, replaying the last 10 days in my mind, two things came clear to me. One was that Route 66 and the CB750 I was sitting on were somehow linked in history: Both had been the only game in town at one point; the best and most popular in their respective fields. Both had gotten old, decayed, and been forgotten. And now, both were experiencing a renewal, a sort of rebirth. This blending of old road and old motorcycles was a good thing, for going backwards in time and reliving a slice of the past gave me a perspective on motorcycling and on life that I hadn’t had before.

The second was that I’d do this trip again in a heartbeat. Just like Bobby Troupe’s hit song says: Won’t you take this timely tip/When you make that California trip/Get your kicks on Route 66.

Yeah, kicks, even on an old Honda 750. Preferably one without a big-bore kit installed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue