THE BIG SWITCH

RACE WATCH

Mitch Boehm

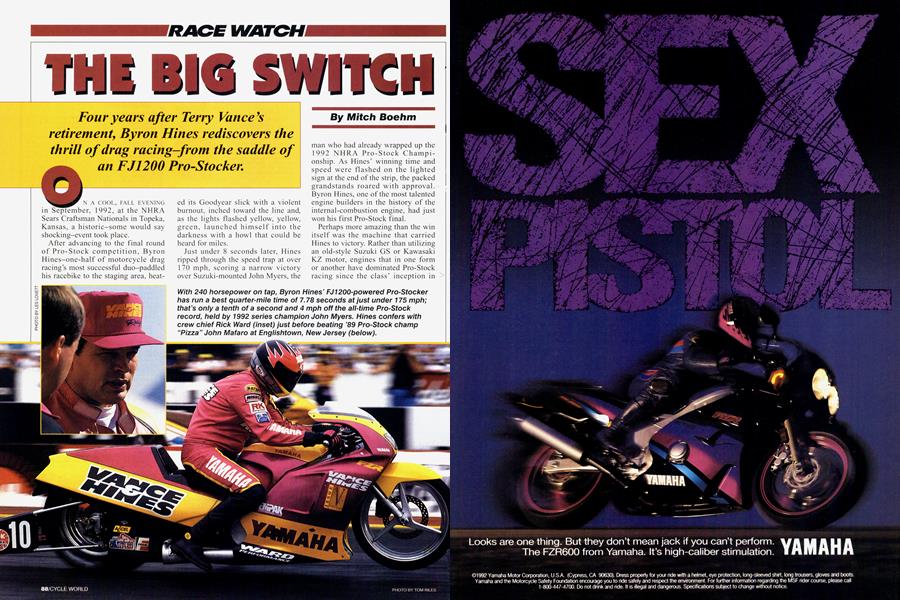

Four years after Terry Vance's retirement, Byron Hines rediscovers the thrill of drag racing—from the saddle of an FJ1200 Pro-Stocker.

ON A COOL, FALL EVENING in September, 1992, at the NHRA Sears Craftsman Nationals in Topeka, Kansas, a historic—some would say shocking—event took place.

After advancing to the final round of Pro-Stock competition, Byron Hines—one-half of motorcycle drag racing’s most successful duo—paddled his racebike to the staging area, heat-

ed its Goodyear slick with a violent burnout, inched toward the line and, as the lights flashed yellow, yellow, green, launched himself into the darkness with a howl that could be heard for miles.

Just under 8 seconds later, Hines ripped through the speed trap at over 170 mph, scoring a narrow victory over Suzuki-mounted John Myers, the man who had already wrapped up the 1992 NHRA Pro-Stock Championship. As Hines’ winning time and speed were flashed on the lighted sign at the end of the strip, the packed grandstands roared with approval. Byron Hines, one of the most talented engine builders in the history of the internal-combustion engine, had just won his first Pro-Stock final.

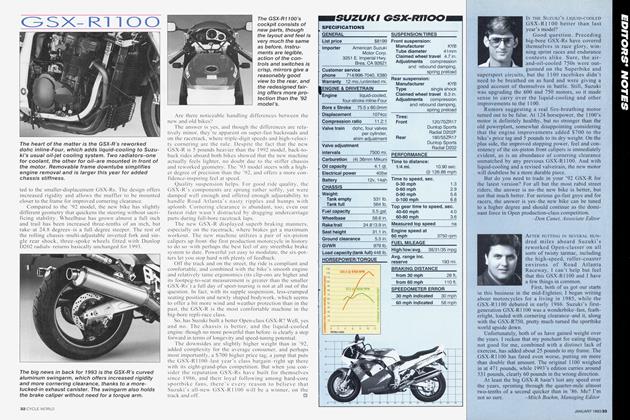

Perhaps more amazing than the win itself was the machine that carried Hines to victory. Rather than utilizing an old-style Suzuki GS or Kawasaki KZ motor, engines that in one form or another have dominated Pro-Stock racing since the class’ inception in 1979, Hines chose a Yamaha FJ1200 powerplant, an engine with no previous Pro-Stock credentials, and one that most knowledgeable onlookers considered totally uncompetitive. The Topeka Pro-Stock win, Yamaha’s first-ever, silenced the doubters.

With riding partner Terry Vance, Hines has contributed his engine-tuning skills to scores of Pro-Stock race wins over the years, but this victory was especially satisfying. Not only had he designed, built and prepared the bike, he’d pulled the trigger and ridden it down Topeka’s 440 yards quicker and faster than anyone else that day.

With so much success already to his credit, one wonders why Byron Hines, a quiet, 43-year-old family man with a wife and three kids, found it necessary to head back into the Pro-Stock ranks as a rider.

“It’s fun, you know?” Hines says in his unassuming manner. “I’ve always enjoyed going racing-the competition, the people.” Then, with a grin, he adds, “I like riding the bike, too.”

As talented as he is with a porting tool or an on-board engine-management computer, Hines has always enjoyed riding and racing motorcycles. After leaving military service in 1971, he began fooling with single-cam 750 Hondas, bracket-racing with success at the many dragstrips that dotted Southern California at the time.

One of these, Lions Drag Strip, a now-defunct facility located near Long Beach, is where Hines met Vance, another weekend bracket racer whose Honda 750s never ran quite as well as his own. The two would become fast friends and eventual business partners at Vance & Hines Performance Products, one of motorcycling’s most successful aftermarket firms. In those early days, there was time for frivolity.

“I remember when my dad bought a Honda 750 for himself,” Vance says, “Byron and I would take it out whenever he would go away for the weekend. I remember doing top-speed runs up and down the Harbor Freeway with Byron at three o’clock in the morning. We did some crazy stuff back then.”

Once they teamed up, first as employees at Russ Collins’ RC Engineering in the early ’70s, then in 1980 at the company that bears their names today, Hines’ riding, at least on a competition level, came to a halt. It was obvious to both where each of their skills lay: Vance’s strength was riding and promotion, while Hines’ gift was squeezing maximum power from an engine and managing a race crew. So organized, they would go on to become one of the most accomplished rider/tuner teams in all of motorsports, notching 14 NHRA titles.

“Byron did what was good for the team,” says Vance. “He never let ego get in the way.”

Toward the end of the 1980s, with Vance planning to retire from competition after a stellar Pro-Stock career, Hines found that he had the desire to get back on a dragbike. He had done a few Pro-Stock races for fun in 1987 on a spare bike, but a nasty crash at Baylands Raceway in northern California that year cooled his enthusiasm. Then in 1990, Rick Ward, who had crewed the V&H drag-race effort for years and had his own performance shop in Minnesota, offered to let Hines ride his shop’s racebike in selected Pro-Stock events. Hines, who was overseeing Superbike engine development and acting as crew chief for Dave Schultz’s Pro-Stock effort, was interested. He found that he enjoyed the racing; he also rediscovered that he was good at it.

As he dabbled with Ward’s bike in 1991, Hines began laying the groundwork for an adventurous plan to build and run a Yamaha-powered ProStocker in ’92. No one had ever run a Yamaha successfully in Pro-Stock competition, yet after looking closely at the air-cooled FJ1200 engine, Hines figured it could be made to work. And since Vance & Hines was contracted to do Yamaha’s U.S. roadracing, it made sense to involve Yamaha with drag racing.

“I figured that making the Yamaha engine competitive would be a challenge,” said Hines, “and it was.”

Armed with support from Yamaha, Hines began work on the FJ project in February of ’92, hoping to have the bike ready as early as possible into the ’92 season. Running the Yamaha engine would allow Hines to take advantage of an NHRA rule that gave a slight weight and displacement edge to powerplants like the FJ’s with a wider valve angle than the Suzuki’s or Kawasaki’s. Those machines would have to weigh 600 pounds with their riders aboard, each bike/rider combination kept at its specific overall weight level through the use of lead ballast weights. The Yamaha could weigh just 585 pounds.

At 185 pounds, Hines is no lightweight, which is one reason he strove to make the FJ Pro-Stocker as light as possible. No exotic materials were used in the chassis, just precise design and engineering. Engine placement is critical to a Pro-Stocker’s performance, so Hines worked closely with Kosman Engineering to come up with a chassis that took advantage of the FJ motor’s relatively small physical size. The motor was positioned up and rearward compared to typical Suzuki or Kawasaki engine placement. The results showed up immediately during testing: The bike launched hard with no wheel hop, and tracked straight at speed. Hines credits the smoothly contoured, FZR-inspired Air Tech > bodywork for a portion of the bike’s high-speed stability.

A huge amount of work went into the FJ-based engine, too, although a casual glance at its exterior gives no clue to the 240 horsepower lurking within. Almost amazingly, the FJ motor utilizes a host of stock parts; the cases, cylinder and cylinder head are off-the-shelf items. Even the crankshaft is a stock part, though it’s lightened and fitted with Carillo rods before it checks in for duty.

“It’s neat,” says Hines, “because you can still buy every single engine part from a dealer. It’s also the only Pro-Stock engine still in production.”

In race trim, the FJ engine displaces 1312cc, the maximum size allowed for its weight level-more displacement is permitted, but there’s a weight penalty. The pistons are special, machined by V&H from Wiseco blanks. The rest of the parts list comprises similarly refined componentry: specially made valves, a handmade transmission set, Megacycle cams, 41mm Mikuni mixers, a hand-bent 4into-1 exhaust and, of course, a full dose of Byron Hines headwork.

What makes the FJ engine unique is its custom “slipper” clutch, an intricate assembly that allows more or less slip-through spring tension and the number of friction plates used-depending on the amount of available traction. Also unique is the bike’s three-plug cylinder head, which, in conjunction with an Empak enginemanagement computer, allows spark lead of just 30 degrees, rather than the 40 degrees required when only one plug per cylinder is used. The threeplug head and ignition mods offer more efficient combustion and-the big bonus-substantially more midrange torque. Along with the bike’s weight advantage, the added torque is a blessing, since the FJ gives up 15 peak horsepower to the top-level Suzukis and Kawasakis, which pump out 255 to 260 ponies on a good day.

“For some people,” says Vance, “15 horsepower is the difference between going racing and staying home.” Hines agrees, but says, “The bike is competitive mainly due to the chassis. It’s light and balanced really well. With another 8 to 10 horsepower, we’d have done a lot better last year.”

Even so, the Pro-Stock FJ is ungodly quick. To get a feel for this bike’s acceleration, consider that it launches from 0 to 60 mph in under 1 second, and from 0 to 100 mph in roughly 1.9 seconds. Kawasaki’s ZX-11, the quickest and fastest production motorcycle on the planet, takes 3.0 and 6.3 seconds, respectively, to do that, which means the FJ Pro-Stocker is roughly three times quicker than a ZX-11.

The Hines FJ debuted at round four of the 1992 series, the Spring Nationals in Columbus, Ohio. Just four months had gone by since Hines began work on the project, yet he was quick qualifier. Though eliminated in the second round due to a blown shifting mechanism, the die was cast-Byron Hines and his Yamaha would be a force to be reckoned with for the remainder of the 1992 season, and everyone connected with Pro-Stock knew it. Five races later at Topeka, after reaching the semifinals at three events in the interim, things finally fell into place. Hines took Myers in the final, giving Yamaha-and himself-a historic victory.

“Early on,” said Byron, “there wasn’t any pressure. We were having fun, and no one took us or the new bike very seriously. But after we started going faster, things changed. There was a lot more pressure, because we knew the bike was capable of winning.”

That alone speaks volumes about bike and rider, for in the four years since Vance and Hines were the dominant force at the dragstrip, things had changed. “These days,” says Hines, “you’ll have all 16 qualifiers within a couple-tenths (of a second) of each other.” Vance nods his head, and adds, “When I was racing, you’d sometimes have five-tenths to a full second separating the field. It’s really gotten competitive; the teams are more professional, and everyone’s got the high-tech parts. But you’ve still got to be smart to run up front.”

Following the win at Topeka, Hines came home to California for the last NHRA event of the season, the Winston Finals at Pomona. Third in points coming in, Hines had no chance of grabbing second or first from season runner-up Dave Schultz or 1992 Champ John Meyers, but he had to finish decently in order to maintain his third-overall position. He did just that, qualifying third fastest and advancing all the way to the semifinal round, where he lost to Schultz, Pomona’s eventual winner.

Third overall for the season was far better than Hines had expected back in February, when he first pulled the FJ1200 engine apart. In just months, Hines had taken an unproven engine, mated it with a newly designed chassis, and put it in the winner’s circle. Of the lightning-quick development process, Vance just shakes his head, points to Hines and says with obvious respect, “That’s what 20 years of racing experience allows you to do.”

And how does the winningest-ever Pro-Stock rider see his partner doing in 1993? “Well,” says Vance, “I wouldn’t want to be lining up next to Byron.”