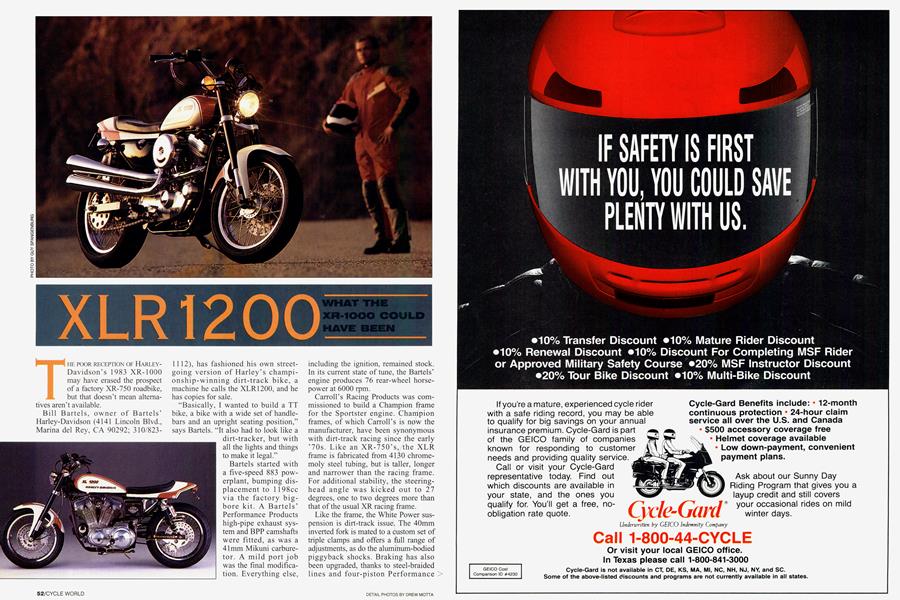

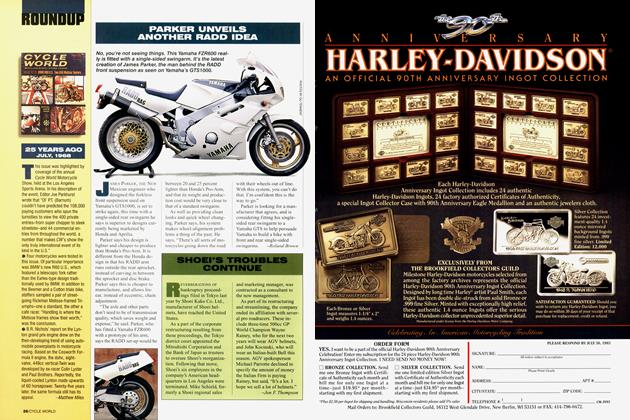

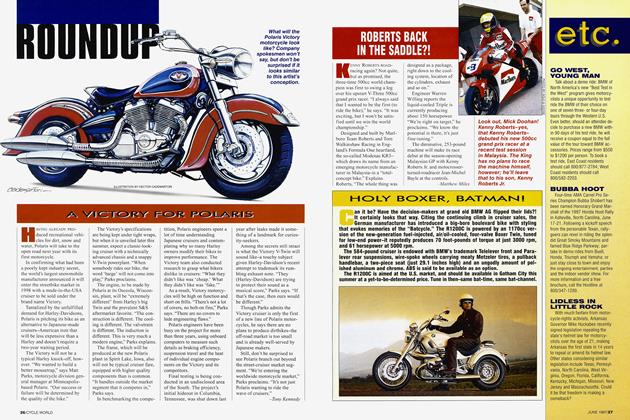

XLR1200

WHAT THE XR-1000 COULD HAVE BEEN

THE POOR RECEPTION OF HARLEYDavidson's 1983 XR-1000 may have erased the prospect of a factory XR-750 roadbike, but that doesn't mean alternatives aren’t available.

Bill Bartels, owner of Bartels’ Harley-Davidson (4141 Lincoln Blvd., Marina del Rey, CA 90292; 310/8231112), has fashioned his own streetgoing version of Harley’s championship-winning dirt-track bike, a machine he calls the XLR1200, and he has copies for sale.

“Basically, I wanted to build a TT bike, a bike with a wide set of handlebars and an upright seating position,” says Bartels. “It also had to look like a dirt-tracker, but with all the lights and things to make it legal.” Bartels started with a five-speed 883 powerplant, bumping displacement to 1198cc via the factory bigbore kit. A Bartels’ Performance Products high-pipe exhaust system and BPP camshafts were fitted, as was a 41mm Mikuni carburetor. A mild port job was the final modification. Everything else,

including the ignition, remained stock.

In its current state of tune, the Bartels’ engine produces 76 rear-wheel horsepower at 6000 rpm.

Carroll’s Racing Products was commissioned to build a Champion frame for the Sportster engine. Champion frames, of which Carroll’s is now the manufacturer, have been synonymous with dirt-track racing since the early ’70s. Like an XR-750’s, the XLR frame is fabricated from 4130 chromemoly steel tubing, but is taller, longer and narrower than the racing frame. For additional stability, the steeringhead angle was kicked out to 27 degrees, one to two degrees more than that of the usual XR racing frame.

Like the frame, the White Power suspension is dirt-track issue; The 40mm inverted fork is mated to a ¿ustom set of triple clamps and offers a full range of adjustments, as do the aluminum-bodied piggyback shocks. Braking has also been upgraded, thanks to steel-braided lines and four-piston Performance > Machine calipers. The wheels use 18inch Sun rims, in 2.75-inch widths, laced to stock Harley hubs with stainless-steel spokes. Tires are race-compound Dunlop 591s in 110/80 and 170/60 sizes.

Rounding out the bike’s dirt-track appearance is its fiberglass tail-section, a genuine XR race part, and an aluminum fuel tank specially made for Bartels’. To make the bike street-legal, a Harley headlight, indicators, mirrors and horn, and a custom taillight assembly were adapted.

With its 433-pound dry weight and 57-inch wheelbase, the Bartels’ XLR1200 is relatively light, compact and fun to ride. The engine’s improved mid-range performance and spot-on carburetion were obvious in both street riding and dragstrip testing, where the

bike accelerated through the lights in 11.9 seconds at 112 mph. In comparison, the last 1200 Sportster Cycle

World tested ran the quarter in 13.0 seconds at 99.5 mph, and weighed 480 pounds without fuel.

Backroad riders will appreciate the leverage afforded by the wide handlebar, the suitably firm suspension and the improved braking of the Bartels’ bike, though real scratchers will probably want to fit double discs, a steering damper and perhaps a fork brace.

Little effort is required to bank into a corner, and ground clearance is

limited only by the folding, stockmounted footpegs. This is no GSX-R, but the XLR will flat carve up a piece of twisty asphalt.

It’s the soulful exhaust note, though, that really captures the essence of dirttrack racing. The lightly muffled twin megaphones are a bit too exuberant around town, calling for religious short-shifting, but once you’ve escaped the confines of the city, the exhaust note is pure enchantment.

We did run into problems with the XLR, however. The abbreviated Sportster wiring harness was ducttaped in place, the throttle-return spring was overly stiff, and a fuel line was improperly routed. Also, the edges of the front fender contacted the fork, quickly rubbing the paint off the expensive legs. But the biggest problem came after less than 90 miles aboard the XLR, when the motor-sprocket nut backed off. The resulting damage to the crankshaft splines required replacement of the crankshaft. This XLR is a prototype, which explains some of the problems, and Bartels says the minor glitches will be cleared up in subsequent bikes. In addition, each bike will come with a 120-day warranty, which would have taken care of our ruined crankshaft.

The asking price for an XLR1200 is $17,900. That’s very expensive, but given the bike’s exclusive status-only 10 running examples will be built-XLRs will not be a common sight. For less-affluent enthusiasts,

Bartels’ will sell a rolling chassis, sans engine, for $12,900. Additionally, all of the parts can be purchased individually.

Still, that’s a lot of money for a TT bike with lights. But until HarleyDavidson has a change of heart and builds an XR for the road, the Bartels’ XLR 1200 provides the look, the feel and the sound of the real thing. -Matthew Miles