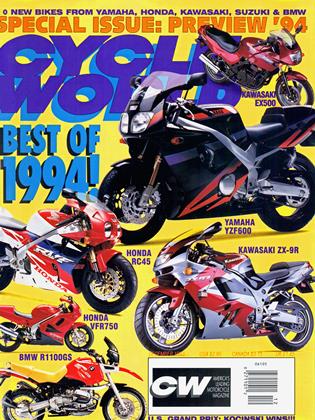

USGP

UNITED STATES MOTORCYCLE GRAND PRIX

Kocinski wins; Schwantz clinches; and everyone misses Wayne

KEVIN CAMERON

THE UNITED STATES GRAND PRIX AT LAGUNA Seca has returned in triumph after a year’s absence, promoted by Kenny Roberts, whose competent KR Promotions organization put attendance for the threeday event at 80,000, with 50,000 on Sunday alone. The 500cc race was won by John Kocinski on the Italian Cagiva, and Suzuki’s Kevin Schwantz is the new 500cc world champion.

Unfortunately, these several fíne achievements were overshadowed by the severe injury of three-time world champion Wayne Rainey at the previous weekend’s GP at Misano, Italy. Rainey is now paralyzed below mid-chest after crashing while leading the race. GP get-offs at 120 mph often mean no more than a severe test for the rider’s leathers, followed by a wrenching tumble. This time it was more than that.

Before the start of the 500 GP at Laguna, the riders on the front row of the grid held up signs saying “Wayne Wish You Were Here,” revealing that recent efforts to turn grand prix motorcycle racing into pure business have fortunately failed. During the week after his accident, Rainey repeatedly spoke to Laguna GP promoter and team manager Kenny Roberts, urging that everyone do his best to ensure a successful event, and waste no time moping. To neighbor and friend Bubba Shobert, Rainey is reported to have said, “Get down to my house and start building me some ramps. I want to get on with my life.” If you’ve ever wondered what kind of power drives a man to come from behind as Rainey has done countless times, the answer is here. Good racers, as Roberts has noted before, do their important thinking ahead of time. Wayne Rainey has clearly done that.

The Misano accident also tends to obscure what came before it. Aware of this, Rainey urged Kevin Schwantz

to remember the hard-earned points lead Schwantz had built up in the first half of the season. Had Schwantz’s mid-season tumble at the British GP not occurred, it is quite likely he would have continued to build up that lead. It was clear from the first GP onward that it was Schwantz and his team that had created the best combination in 500 racing. Rainey’s crash did not in any sense “hand” Schwantz the title. Schwantz has, after years of struggle, understood and overcome his own nature-his reflex to win comers and races rather than championships-and his team has produced the tightest-turning and most ridable machine in the class.

Politics is GP racing’s middle name. Three or four seasons ago, the sport’s ruling body, the FIM, tried to force a switch from two-stroke engines to

four-stroke. This triggered a many-sided struggle among the teams, the FIM and the new forces associated with promotion and TV, leading to a new balance of power. The FIM has had to accept reduced status, while an uneasy coalition of Bernie Ecclestone’s Two Wheeled Promotions, the European TV giant DORNA and the team association IRTA mies the sport on an ad hoc basis. This season, Ecclestone is said to have cashed out at least part of his ownership of GP racing to DORNA. Why? Some paddock residents just put their heads down and continue with their business, while others speculate, inventing byzantine theories.

In the meantime, paddock conversation also is occupied with a curious technical problem: Why are the 500s so slow? At many circuits, the fastest 500cc lap times were achieved in 1991, and have either stayed at that level since or have actual>

ly become slower. There is no lack of power; top 500s have come up at a rate of at least 5 horsepower per season, sometimes more. The most powerful machine, Honda’s NSR, may give over 180 horsepower now. Meanwhile, both the 125 and 250cc classes have become faster-seconds faster.

This is worrisome to the teams, for they know' that there’s a noisy international clique of critics who use every excuse to bray, “500s are too fast and powerful for human reflexes; they must be banned.” This has been going on since near the beginning of the century, when lap speeds were only half of what they are today, and it will no doubt still be going on when this century is over. The present facts show that this remains nonsense.

If 500s were unridable and getting worse, there would be fewer and fewer riders able to ride them. In fact, the opposite is true; today, the 500cc rider base is wider than it has ever been. In the bad old days of 1988-89, when the infamous corner-exit high-side accidents were interrupting the careers of top riders, it’s true that the races were won exclusively by men with big-bike experience. It was an accepted truism that no one from the 250 class could hope to become a 500 ace-and many had tried.

Today, all is different. Luca Cadalora, twice 250cc world champion (1991-92) won two GPs this year, becoming a serious threat to his own teammate, Wayne Rainey. We can look to history for explanation. W’hen 750 two-strokes appeared in U.S. racing in 1972, at first only supermen like Y von DuHamel could ride them. But when Yamaha released a much-refined and more-ridable machine-the TZ750D-in 1977, there was suddenly a crowd of fast riders at the front. Technology has now civilized 500s in a parallel way. At

first, it was easier to build up horsepower because that's an old technology. Chassis and suspension took longer because they deal with new problems. Finally, a breakthrough came in 1990-91, with the perfection of engine-torque controls and anti-spin systems. With these, corner exits were transformed from violent, slip-and-grip affairs with riders hanging on to their bucking, weaving machines like rodeo stars, into relatively smooth, fast launches. And most recently, Honda committed its “Big Bang” engine concept at the beginning of 1992, giving rider Mick Doohan an off-corner advantage that would have made him world champion last year had he not been injured.

A Big Banger fires all its cylinders within, say, 70 crank degrees, and then coasts for 290 degrees before firing again. This delivery of torque in big pulses smears out the formerly tricky transition between gripping and sliding, making machines much more controllable during acceleration. It may also actually increase traction, working like anti-lock brakes in reverse, breaking loose the tire minutely, then giving time for it to regain grip before hitting it with another torque pulse. Today, all the top teams use Big Bang engines, resulting in the most ridable 500s we have seen in many years.

nother 500cc problem-thinning start grids-has also been solved. After much prodding from Kenny Roberts and others, Yamaha is manufacturing and selling its V-Four engine in quantities. Harris in England and ROC in France have built suitable chassis, putting many privateers back into 500 GP racing. The usual 12 to 14 factory machines are now supplemented by eight to 10 ROC bikes and a similar number of Harris machines.

This is fine, but it still doesn't answer the question: Why aren’t the 500s faster? Asked, veteran race engineer Kel Carruthers replied with another question: “Why are 250s so fast?” In 250cc qualifying, 12 riders w'ere under the lap record, with top man Foris Capirossi (Honda NSR) some 1.4 seconds quicker than John Kocinski's 1990 mark. Yet the 500cc record failed to fall, even in the race itself. The fastest 1993 500 qualifying lap was Doohan’s 1:26.42, set on a machine that is 30 horsepower stronger than the Suzuki used by Schwantz to set the 1990 record of 1:25.83.

One source of answers was practice. As a first cut, you could divide the field into Doohan’s Honda, and all the others. Doohan’s bike is visibly far more powerful than anything in the field, and he was riding it with desperate decisiveness. The power hurled him down Laguna’s short straights, obliging him to get sharply on the brakes to destroy the speed just created, in order to get safely into the next comer. By contrast, Barros and Schwantz on the Suzukis were going nearly as fast, but looked much more relaxed, riding the track in graceful combined movements, not being forced by excess power to break it up into violent, separate segments.

Another division comes between Luca Cadalora and most others. This is his first season on a 500, and pundits at the opening GP in Australia were deploring what they described as, “Trying to ride a 500 as if it were a 250.” The accepted style for the 500 class was defined by Kenny Roberts back in 1978: Come in slightly slow, so as to be able to hook around quickly, then use the extra room this provides to accelerate out hard, sliding and steering with the back wheel in dirt-track style. The desired result is a high exit speed that helps the rider all the way down the next straight. Previous attempts to use a 250-like style, which emphasizes high cor-

ner speed and lean angle, have failed; when Ron Haslam and Christian Sarron did this, poor tire grip at high lean angle killed their initial acceleration, allowing the “dirttrackers” to jet past them.

adalora is more sophisticated, as you might expect from a studious man whose face is a smoldering furnace of ambition. He cannot permit himself to be unable to do what he has seen other men do. As he said in Australia, “I am unaccustomed to racing for seventh place.” Now Cadalora has begun to win races.

Riders who steer the rear wheel with the throttle like firm spring and damping rates that, by reducing grip, help the process of snapping the rear tire loose when power is applied. Firmness is also useful when entering comers; with less time wasted in compressing suspension, the machine reacts more quickly and positively. Also, a firm setup helps to avoid the change of attitude that can occur as the rider opens up off a comer.

If a little is good, more may seem better, and in time a rider’s style may become so wedded to the benefits of a hard ride that he can no longer perceive the major problem it causes: reduced ability of the tires to track over bumps and grip the pavement. Everything is a compromise, notes Suzuki’s tech guru, Stuart Shenton. “Really, you’d like four different motorcycles, one for each of the four phases of getting through a corner. You’d like one that was well-balanced and stable under brakes. You’d like another with light, quick steering that would turn into the comer well. You need a third for the special conditions of steady-state turning. And then you’d like a fourth type that resists squatting

and tucking its front end as the rider gets on the throttle.”

A simple “solution” (read “compromise”) is to largely do away with the suspension—on a smooth track, a rigid machine is close to ideal. But times change and fresh problems appear. Each time the suspension is made stiffer, more of the bending is transferred to the chassis. Bumps then set the chassis into vibration, which upsets stability during the critical corner-exit phase. To counter this, the engineers make the chassis stiffer to stop its unwanted flexing. That process has worked well for a long time to elevate chassis capability-in GP racing, in Superbike, on the street. Now it has stopped working for 500cc grand prix bikes. At the first 1993 GP, the factory Yamahas appeared with freshly stiffened chassis and no one could make them hook up. As Wayne Rainey said then, he had “chatter, hop and skating.” A machine in a comer has three mechanisms of suspension. There is the flexible tire carcass, there is the suspension proper and there is the twisting of chassis and swingarm. The fascination of engineers with the rapid technical development of tires and suspension has tended to obscure the importance of chassis twisting as a supplemental suspension. Radial tires are

good springs vertically, but when rolled almost onto their sidewalls (as in a corner) they become stiffer. Suspensions have, as noted above, been made steadily stiffer-and at high lean angles are simply pointed the wrong way to absorb bumps. And now that chassis have become so extremely stiff, with giant fork tubes, axles and chassis beams, there is literally no part of the machine left that is soft enough to absorb bumps properly.

The result is poor grip, as bumps throw the tires into the air. A few seasons ago, Öhlins technicians used a profilometer to measure the total up-and-down excursion of the surface of a certain track, on the racing line. Then they used an onboard computer and sensor to measure the total up-and-down movement of the bike’s rear wheel. Result? Wheel movement was less than half of the actual track excursion. That suggests that tires are off the ground much of the time, and that suspension is not highly efficient.

Cadalora says he likes to have the suspension move more than is currently considered proper, because “it puts me in touch with what the tires are doing.” In doing so, he has restored some of the grip lost in the long stiffening process. With that added grip, he is able to accelerate successfully from his high-lean-angle, in-comer attitude. In Laguna’s Turn 5, Cadalora was the only 500 rider grounding his fairing. It is said that even Rainey himself used some of Cadalora’s settings this year.

Doohan’s Honda, running on the tight Laguna circuit, shows the ultimate contradiction of using horsepower to reduce lap times. At lower speeds, more power just spins the tire or lifts the front end, so it’s useful only at higher speeds. Any speed gain from this extra acceleration then forces the rider to shut off sooner, to brake for the next turn. Thus, increasing power actually shortens the time during which the rider can use the power. On long tracks like Hockenheim in Germany, power helps. At Laguna, it doesn’t. More is less.

W: etching practice at the exit of Turn 9 was instmctive. Going under the pedestrian bridge here, 250s are solidly on-throttle, leaned far over, going very fast. By contrast, even after five laps for tires to warm up thoroughly, the top 500 riders are only able to crack their throttles to idle, engines firing irregularly. They are neither leaned over as far nor going as fast as 250s here. I asked Kenny Roberts about this situation.

“They’d open up more if they could, but they can’t. Too much power,” was his terse reply.

A 500 engine is not like a streetbike engine, able to give the full range of power from idle to peak. As the racebike’s throttle is opened, it almost doesn’t fire at all. A racing engine must have large ports, and the whiff of mixture let in by a small throttle opening gets lost or diluted to unfireability by all the swirling exhaust product and won’t bum regularly. The engine surges and makes the two-stroke’s famous “ring-a-ding” noise. At some larger throttle opening, the engine gets enough mixture to fire steadily, but is now making quite a lot of power-perhaps 30 or more horsepower. If this is too much for the situation, as it clearly was at Turn 9, then the rider has only one choice: to apply no power at all.

This situation used to be far worse, but has been improved a lot by throttling the exhaust with an exhaust gate, which closes down at part-throttle to make it harder for mixture to get lost, thus extending the range of steady firing down to lower throttle positions. But there are limits to this. Roberts noted, “When you increase the power range, you start to lose top-end, and then what’s the point of even having a 500?” On a tight track, this lack of usable, small-throttle power considerably delays the first application of power after each tum. The 250s, with less power, can use it more of the time. No surprise, therefore, that on some circuits 250s are only a few tenths of a second off 500cc lap times. What’s important is not peak power; what counts is power actually applied, multiplied by the time it is in use-call it horsepower-seconds per lap. Measured this way, the actual delivered-to-the-track power of a 95-horsepower 250 may not be much less, on some circuits, than the same figure for a 180-horsepower 500.

Still skeptical? How about this, then? One of the 500cc team managers led me to his computer rack, where a few keystrokes pulled up a display of time spent at various throttle openings, the data having been gathered by onboard computer. For Laguna Seca, time at full throttle is less than one percent. An engineer from another team later told me that a good average for full-throttle time on European circuits is 10 percent or less. That puts horsepower in perspective, and it shows how more can be less. It also shows what 500cc racing really needs; a motorcycle that can apply its power a higher percentage of the time.

It’s easy to be fooled in this business. An engineer, seeing Schwantz outaccelerate other riders through a complicated direction-changing maneuver, may believe it is an abundance of bottom power that makes this possible. He goes back to his factory and builds more bottom power, but his team’s motorcycle goes slower yet. Baffling? In fact,

Schwantz is outaccelerating the others not because he has more power, but because he has less-power low enough and controllable enough to actually use, while the super-power opposition has too much to safely use, and must coast through tricky sections.

That combination was exactly what Schwantz and Suzuki were aiming at between the 1992 and 1993 seasons. An early test was made, back-toback, between one of Suzuki’s most powerful 500s on the one hand and a machine given an intake system optimized for lower-rpm power on the other. After riding the second machine, Schwantz reportedly said, “I can ride this one.” In effect, what they were developing was a “street-bike with top-end,” a machine with more manageable, wider-range power, so that the rider could use that power, not in larger quantity, but more of the time. This scheme has worked before. Giulio Carcano’s single-cylinder Moto Guzzi couldn’t keep up with multi-cylinder opposition in a straight line back in 1953-57, but its handiness and usable power won five world titles.

Everyone respects Mick Doohan for his brilliant riding of the Honda, but the number of accidents he has shows that his workload is just too high for consistent results. This kind of problem is well-understood in aviation circles, where workload is now carefully monitored to prevent unnecessary “mismatches” between man and machine. Nevertheless, horsepower remains Honda’s major strategy, and at Laguna, you could see Doohan taking measures to protect his tires from excessive spin-and losing ground as a result. At places like Hockenheim, the sheer speed of the Hondas is majestic-nothing can come close-but at tighter tracks like Laguna, it’s a different story. Here, it’s as though the Honda rider, exiting a comer, tosses a few sticks of dynamite over his shoulder, hoping that the resulting explosion will blow him to the next comer. Any lack of precision must be corrected by the rider’s skill, and it’s hard to get it right 100 percent of the time.

But, again, although these considerations are suggestive, they don’t fully explain why 500s are so slow. I spoke to David Watkins, Dunlop’s race tire designer. He replied that the great size difference between front and rear tires on a 500 makes it difficult to flick quickly into a comer. I remembered something similar that KR had said back in 1982, after Dunlop released the first 8-inch-wide rear: “It’s like driving a racecar with a locked rear axle. The long footprint of the big tire resists being twisted sideways by the front tire.”

Although other technicians at Laguna mentioned this same effect, and it appears that narrower but taller rears will soon be forthcoming, this tum-in resistance doesn’t explain why 250s should be on the gas in steady-state turning, while 500s are coasting, their riders waiting to get to where they can safely open up. I then asked Watkins whether the tire companies might have voluntarily decided to back away from the traction technology of the “high-side” era, when all the top riders were tossed onto their heads as they found the sudden release that lay just beyond these tires’ amazing grip. He nodded briefly, as though this might have some truth. Others I asked rejected the idea, saying that tire makers wouid do whatever it took to win. I wasn’t so sure. With all the bad press those tires generated, management might simply say, “No more of that. We can’t stand the heat. If any more world champions go into the weeds, your whole department is going with them!”

Now came an important piece of investigative luck. One of the team engineers volunteered this remarkable story: “Remember the ‘killer’ high-grip tires of 1988? Well, I kept one of those, thinking I might need it one day. And this season we did need it. We put it on, and with no other change, went a full second quicker in qualifying.”

Bang, there it is, the major reason 500s aren’t going faster. The tire makers are intentionally pulling their punches. The marvelous thing about this development is that it shows how compartmentalized race engineering now is. That old “killer tire,” when combined with a modem Big Bang engine, was no more dangerous than any other. The tire companies have been giving the 500 class what they think is needed, without fully appreciating the significant developments that have occurred in the meantime.

Both Dale Rathwell (suspension consultant to the Vance & Hines Yamaha Superbike team) and Erv Kanemoto (GP

engineer with many 500 and 250cc world titles to his credit) rather wistfully expressed the wish that they could take a sabbatical from their present professions to spend six months with a tire company, learning more about tire engineering and trying to create a new integration of that knowledge with what they already know about motorcycle handling. Despite all the earnest meetings that are no doubt held between tire engineers and race teams, it is still as though the overall enterprise were divided into sealed boxes. No one can truly speak freely, for everyone knows that Team Manager X may get a better offer for next season from Company Y, who are contracted to Tire Maker Z, and that might let out all kinds of secrets.

And so amazing things happen, such as the technician of a major tire maker stating that, “Rubber is rubber. When you heat it up and cool it down again, it’s the same as before.” Any racer knows this isn’t true; racing rubber is chemically “alive,” and any heating of it, whether in curing, in the trackside tire-warmer or by hot use on the track, drives the rubber along its cure curve, changing it irreversibly. Either this technician was told only what his superiors wanted him to believe, or he is poorly trained indeed. As Paul Litchfield, a former president of Goodyear, noted a lifetime ago, secrecy usually keeps out more information than it keeps in.

I here you have it. Laguna presented four theses on how to win: 1) Honda power; 2) the tradi tional dirt-tracker riding style; 3) Suzuki's ridable "streetbike with top-end"; and 4) Cadalora's soft-suspension, high-corner-speed method.

Doohan showed that with enough riding talent, power can still work. He led the race by 2 seconds before again falling after exiting Laguna Seca’s tricky Corkscrew. The traditional style won the championship for Kevin Schwantz, and was the basis for Wayne Rainey’s brilliant defense of his title. Suzuki’s efforts to produce a more ridable 500 contributed much to Schwantz’s title, and have made a real threat of teammate Alex Barros. Finally, both the race winner,

Kocinski, and thirdplaceman Cadalora are still accused of trying to ride a 500 like a 250. Now it’s clear that is no crime, but may be the wave of the future. There is plenty of fresh conceptual growth in GP racing, and the 1994 season should bring significant change.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

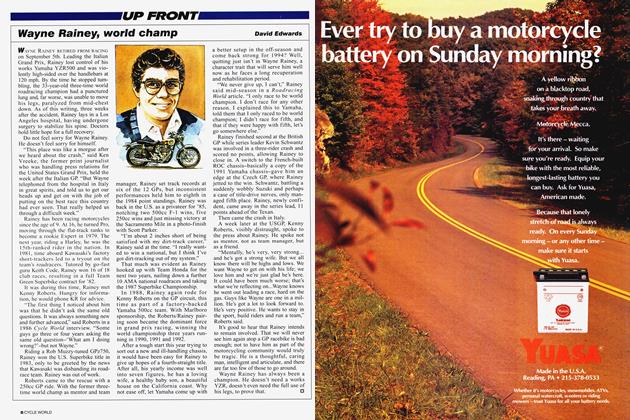

Up FrontWayne Rainey, World Champ

December 1993 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsTriumph Motorcycles In America

December 1993 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCAnother 100 Years?

December 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki For 1994: Out With the Old, In With the New

December 1993 By Don Canet -

Roundup

RoundupAnother Excellent Oddball From Ktm

December 1993 By Jimmy Lewis