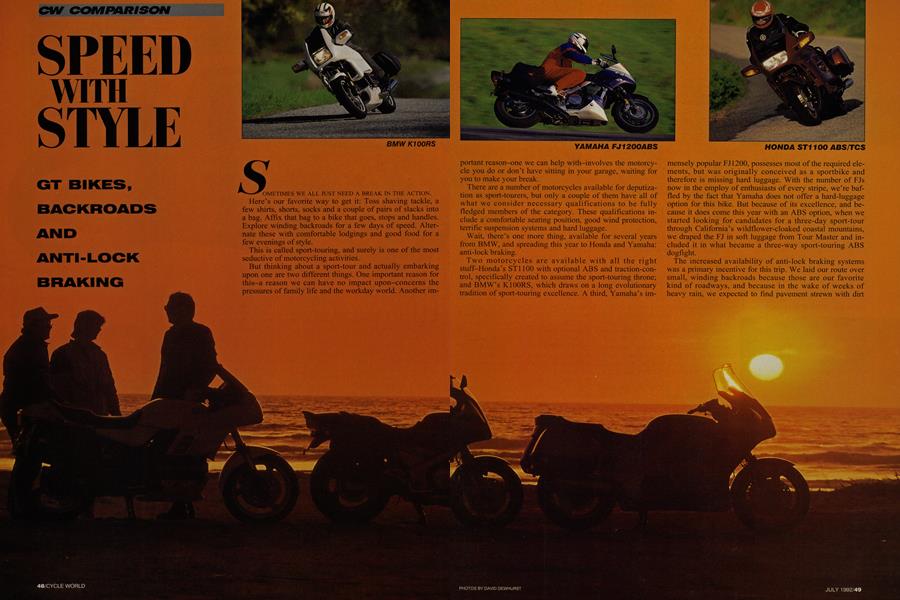

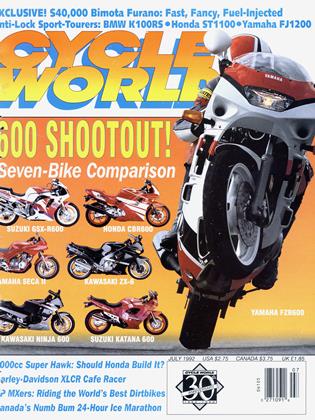

SPEED WITH STYLE

GT BIKES, BACKROADS AND ANTI-LOCK BRAKING

CW COMPARISON

SOMETIMES WE ALL JUST NEED A BREAK IN THE ACTION. Here's our favorite way to get it: Toss shaving tackle, a few shirts, shorts, socks and a couple of pairs of slacks into a bag. Affix that bag to a bike that goes, stops and handles. Explore winding baekroads for a few days of speed. Alternate these with comfortable lodgings and good food for a few evenings of style.

This is called sport-touring, and surely is one of the most seductive of motorcycling activities.

But thinking about a sport-tour and actuaTly enibarking upon one are two different things. One important reason for this-a reason we can have no impact upon-concerns the pressures of family life and the workday world. Another im portant reason-one we can help with-involves the motorcy cle you do or don't have sitting in your garage, waiting for you to make your break.

There are a number of motorcycles available for deputiza tion as sport-tourers, but only a couple of them have all of what we consider necessary qualifications to be fully fledged members of the category. These qualifications in clude a comfortable seating position, good wind protection, terrific suspension systems and hard luggage.

Wait, there's one more thing, available for several years from BMW, and spreading this year to Honda and Yamaha: anti-lock braking.

Two motorcycles are available with all the right stuff-Honda's ST1 100 with optional ABS and traction-con trol, specifically created to assume the sport-touring throne; and BMW's KIOORS, which draws on a long evolutionary tradition of sport-touring excellence. A third, Yamaha's im mensely popuTarFJI200, possesses most of the required ele ments, but was originally conceived as a sportbike and therefore is missing hard luggage. With the number of FJs now in the employ of enthusiasts of every stripe, we're baf fled by the fact that Yamaha does not offer a hard-luggage option for this bike. But because of its excellence, and be cause it does come this year with an ABS option, when we started looking for candidates for a three-day sport-tour through California's wildflower-cloaked coastal mountains, we draped the Fi in soft luggage from Tour Master and in cluded it in what became a three-way sport-touring ABS dogfight.

The increased availability of anti-lock braking systems was a primary incentive for this trip. We laid our route over small, winding backroads because those are our favorite kind of roadways, and because in the wake of weeks of heavy rain, we expected to find pavement strewn with dirt and gravel, and therefore tailor-made for ABS. Our expectations were ful filled, in more ways than one.

We expected the weather and the scenery to be superb. They were. We expected all three bikes to perform re liably. They did. We expected them all to be as different from one another as possible. They were. As experienced riders with lots of braking prowess, though, we didn `t expect to become true believers in ABS. But we are.

Oddly enough, the bike we wanted the most to like, we found the most difficult to like. That would be the BMW. Look at it. It's gorgeous, beau tifully and tightly sculpted, a rolling example of all the tradition and charis ma for which BMW is so justly famed.

By itself, the K100RS is a satisfying bike, with its great looks, high-tech personality, high-speed, straight-line stability and tight, solid feeling. The bike's brakes, especially the front brake, have by far the best feel of any set of brakes in this group, and the BeeEm is the one bike in this group that comes equipped with premium tires-Michelin radials, in this case. The bike's unusual left-bar, right-bar switchgear, its instruments and fairing all got especially high marks. One tester noted, "These conspire to give a real `cockpit' feeling." Unfortunately, the Beemer has some odd weaknesses that are tough to overlook.

First, it vibrates-so much so that at speed, it anesthetizes toes, and its mir rors report only vague forms. Second, its engine makes adequate horsepower, but only at high rpm, instead of in the midrange, where you want oomph from a sport-tourer. Its top-gear roll-on figures are better than the ST's, but only because the ST has a much taller top gear than the Beemer. Third, by comparison with the other two bikes in this group, the K100RS steers slowly and feels top-heavy. And last, its sus pension needs work. The fork, which offers no adjustability, is so signifi cantly underdamped that quick paces over bumpy roads set the bike's front end oscillating up and down. At the rear, the bike's single shock is ad justable for preload and for rebound damping, but the damping adjustment range is so small as to be infinitesimal. Even with rebound damping turned to full-hard, the bike still wallows badly when leaned over in a bumpy corner because the shock is rebounding too quickly.

`Ihis is not acceptable behavior trom a machine that costs $12,990. For that kind of money, it seems reasonable to expect the bike to be fully and com pletely sorted, and fully capable of the

high-performance touring at which it is so clearly aimed. For that much money, it also seems reasonable to ex pect the RS's paint to be smooth and flawless. Our test bike's metallic pearl paint was splotchy and uneven.

As noted, we wanted to like this bike. And in some ways, we do. Rid den at a moderate pace over smooth roads, it's a blast. Non-motorcycling observers react very positively to the Beemer, and that's fun, too. But in the universe of sport-touring riding situa tions, the K100RS is not as bright a star as we had hoped.

That the Yamaha FJ1200 is consid ered a member of the sport-touring fra ternity is as much a testament to the brilliance of the bike's design as it is to the changing direction of motorcycle marketing. When it was conceived in 1984 as the FJ1100, if you wanted a sport-tourer, you bought a BMW. The FJ, on the other hand, was a rock `em, sock `em Open-class sportbike.

Today, better sportbikes abound. But there may be no better single allrounder than the big FJ, which has been the subject of careful refinement. The bike's displacement has been in creased to 1188cc, and for the 1991 model year, its engine received a Nor ton Isolastic-esque mounting system that smooths out the worst of this big banger's vibrations.

As with tile 13MW, the Yamaha ot fers a lot to like. Its air-cooled engine, as always, is wonderful, with enough lowand midrange stomp to satisfy a! most anyone, and with enough high rpm horsepower to please all but the most jaded Open-class nutters. And thanks to the new engine-mounting system, it's very smooth, though a few vibes do seep through at engine speeds of less than 4000 rpm.

At 578 pounds dry, the FJ12, while no featherweight, was the lightest of this group, and was the easiest and most fun to flick through high-speed backroad corners. Its upper fairing pro vides the best-though not necessarily the most-wind protection, and its wide bars, easy steering and gas-it-and-go nature combine to provide an almost effortless seven-tenths backroad sporttouring pace. The bike is an absolute blast to ride, in spite of several signifi cant weaknesses. Those include clunky downshifting, too little distance be tween the seat and footpegs for taller riders, seat foam that's far too soft and a fork that is, though adjustable for preload, greatly underdamped in both directions. You especially notice this last point when braking hard for a cor ner over a series of bumps. The fork will slam down onto its stops, bottom ing hard and then rebounding quickly.

The FJ' s two-way-adjustable shock, on the other hand, performs very well, and can be adjusted to provide any kind of ride, within reason, you desire. The knurled rebound damper knob is found at the bottom of the shock, and is easy to reach. The preload adjuster, on the other hand, is a pain to get to. To find it, the seat's got to go, and so does the left side panel. Then you've got to reach way in with a special ad juster provided in the toolkit, and make the adjustment. At least the effort re quired to get the shock set up is worth the result.

Perhaps the bike's most important problem, at least from a sport-touring point-of-view, is the omission of hard luggage from its options list. Give the bike luggage, firm up the seat foam, upgrade the fork, and the old girl will have a terrific sport-touring career ahead of her.

Ihe tinal member ot this trio, Honda's ST1 100, offers by compari son very little for us to complain about. And that should be the case. Honda started with a clean sheet of paper when it introduced the bike three model years ago as a fully developed sport-tourer, and got it almost com pletely right. The bike is minimally changed for 1992; the only deviations are the bike's red paint (it was black its first year, silver its second) and the ad dition of a screwdriver hole in its right sidepanel through which the rebound damping of the single shock can be ad justed.

Mostly, the big Honda shines. Its look, like its V-Four engine, is just a little automotive, and for true motorcy cle believers that can be a little offputting. But, the engine, especially at low rpm, and when kept out of its overdrive top gear, feels as torquey as any other motorcycle engine you'll ever lay the wheat to, with the excep tion of the FJ12's engine. It makes all the horsepower most sport-touring rid ers ever will want-enough to haul its considerable bulk to a top speed of 128 mph-yet delivers sufficient fuel mileage, especially at cruising speeds, to make possible a cruising range of up to 300 miles from its 7-gallon fuel tank. On a very hot day, though, you won't want to go that far. Our test bike leaked an uncomfortable amount of hot air from the radiator-ducting system onto the rider's left shin and knee.

The ST's windscreen also could use some attention. It's noisy, and it causes turbulence that buffets the helmets of taller riders. We'd like to see Honda offer some optional screens that would allow the ST buyer to tailor the bike's wind protection to his liking.

One final point: A premium bike like this ought to wear premium radial tires. The ST does not. The Bridge stone Exedra bias-ply tires on our test bike worked well enough, but quality in tires is like quality in brakes: More is better, especially at the ST's price$11,199, a stiff $1900 more than a non-ABS/TCS ST1 100.

BMW K100RS ABS

$12,990

Honda ST1100 ABS/TCS

$11,199

Yamaha FJ1200 ABS

$8499

HORSEPOWER! TORQUE

The Honda is a big, heavy bike, one we've begun thinking of as the "Sport Wing." For it is, in most respects, as comfortable, commodious and compe tent as a Gold Wing. It's also nearly as big. Yet because of its terrific engine, well-conceived transmission ratios and beautifully calibrated suspension, when you want to make serious time over a winding road, hauling luggage and perhaps a passenger, this is the bike. Unless you're sufficiently silly to subject this heavyweight to full-on sport-riding techniques, it is very diffi cult to force the ST's suspension to lose its composure. For these reasons, the ST1 100 is the sport-touring ride of choice.

But what about brakes? What about ABS? First of all, every bike ought to have a front lever feel like that of the BMW. Squeeze the thing, just a little, and you stop. The feel through the lever is firm and solid, and allows you to sense exactly what's happening down there where brake pad meets rotor. Both the FJ and ST ultimately stop more powerfully than the BMW, but without that sensational brake feel, and with considerably higher lever pressure.

The Japanese bikes shine when it comes to ABS, though. Here, the Honda's system takes top honors, with a rapid lever pulse that is barely felt, especially at the front. The ST's pulse, felt as the computerized system adjusts the hydraulics to tighten and loosen the caliper's grip on the rotor as traction is gained and lost, seemed somewhat more refined than that of the FJ, though the bikes' respective systems allowed them to stop with remarkable consistency during performance test ing. The BMW's system felt the least refined of the three, cycling more slowly and plenty willing to do mini front-end tucks between ABS cycles, and nowhere nearly as consistent in re peated emergency stops as the systems of the Japanese bikes. BMW officials say a second-generation system is in the works.

The ST's traction-control system works in conjunction with its ABS sys tem, working off the same rear-wheel sensor used for the ABS to make it ab solutely impossible, when the system is turned on (unlike the ABS systems on all three bikes, the Honda's TCS can be disarmed), to spin the bike's rear tire. When the system senses tire spin it stutters the ignition as much as is required to maintain traction. The ST's regular power delivery is so smooth and gradual that we're not sure it is the ideal recipient of traction con trol. So we'll withhold judgment on TCS, at least for now.

We won't, however, withhold judg ment on ABS. It is, we believe, an idea whose time has come, particularly on sport-touring bikes.

[he very backroads that most rid ers search out for their sport-touring trips often are the ones that receive the smallest amount of attention from highway-maintenance authori ties. So they are by definition the ones where the sport-touring rider is most likely to find dirt and gravel right where he least desires to see such distractions-right smack where he wants to begin braking for an upcoming corner. Isn't there a corollary of Murphy's Law that reads, "Slippery road surfaces are always found where they can do you the most harm?"

We all know that, and as a conse quence, anyone who rides motorcy cles has very highly developed abilities to read pavement, and to spot troublesome areas. Still, we all make mistakes. ABS, it seems, can help minimize the consequences of those mistakes. It absolutely will not allow you to lose traction while traveling in a straight line on slip pery surfaces as a result of too much braking. The flip-side of the coin is that ABS does not necessari ly shorten stopping distances. Be cause of the way it works, it can, in fact, lengthen them by at least sev eral feet, even in ideal conditions. So it must be used advisedly.

In the real world, even when things are dry, pavement is not al ways perfect, and sometimes is gar nished with a pinch of gravel, a dollop of water or a patch of oil. There, where most of us ride, ABS is a very, very good idea. Some bikes, like touring and sport-touring bikes, can benefit from it on both wheels. Others, like sportbikes, might best use it at the rear wheel, in an application which would give new-found usefulness to rear-wheel braking. But whether the expense of ABS ever falls to a point where rid ers won't wince at its price premi um-well, that remains the question. For while the BMW comes with it as standard equipment, it's a $1400 option on the FJ and a $1900 option on the ST. Can you get along with out it? Of course. Should you have to? Probably not. If you're consid ering one of these bikes, should you buy the ABS option?

It's all a matter of weighing the costs-financial and otherwise.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAndy Rooney Rides

July 1992 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Whites of Their Eyes

July 1992 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCA Matter of A Pinion

July 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1992 -

Roundup

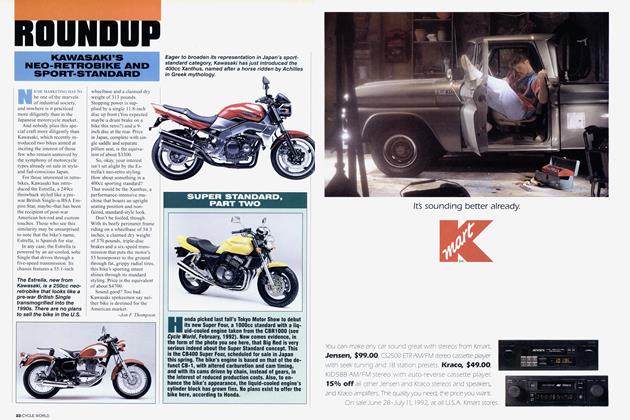

RoundupKawasaki's Neo-Retrobike And Sport-Standard

July 1992 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

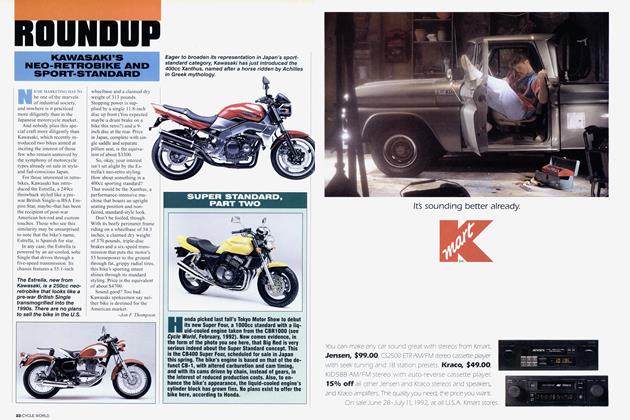

RoundupSuper Standard, Part Two

July 1992