UP FRONT

Motorcycles for America

David Edwards

FOR A MAN WHO MAKES HIS LIVING critiquing other people’s motorcycles, I own a quartet of collectible machines that’s a pretty sorry lot. Oh, they’re great fun, all right, but not one is suitable for everyday use.

My 1946 Velocette GTP has no rear suspension, a top speed of 45 mph and a propensity for seizing. Even Velocette company officials used to joke that GTP stood for “Generally Tight Piston.” My 1954 BSA isn’t bad, really, except when it refuses to kick-start or fouls its sparkplug, which is just often enough to keep me religious. My Honda VF750 Superbike racer has been made minimally street-legal but is so loud that I truck it to backroads, for fear of being pulled over in town and issued the Fix-It-Ticket-From-Hell. My latest project is another racer-turned-street-bike, a Yamaha 750 flat-tracker based on an XS650 Twin; it has neither speedometer nor fork lock, and it needs refueling every 75 miles. Peter Egan calls my motorcycles “The world’s greatest collection of bikes you can ride for a half-hour.”

If you wish, use that assessment as a filter for what follows, but I’ve taken a long, hard look at what the motorcycle makers have to offer for 1992 and discovered some gaps in desperate need of filling.

The sportbike front is pretty well handled, though it might be fun to see Honda throw a little NR technology at the masses. How about a carbon-fiber, oval-piston, lOOOcc VTwin that weighs 350 pounds and pumps out 100 horsepower? And why Yamaha doesn’t have a massproduced 750cc sportbike based on the OWO1 racebike remains a mystery.

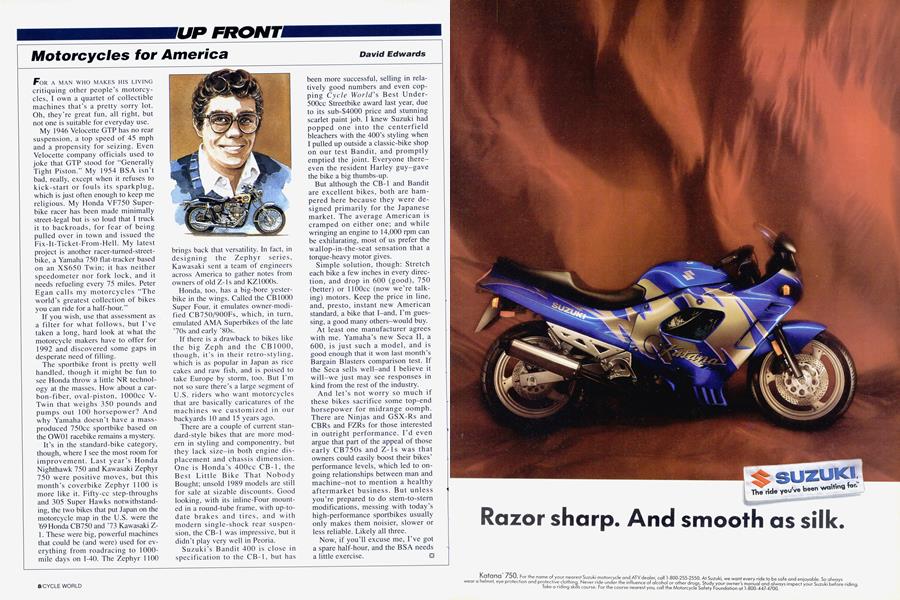

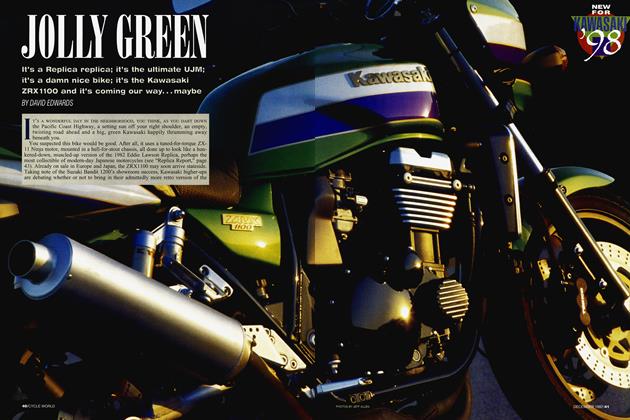

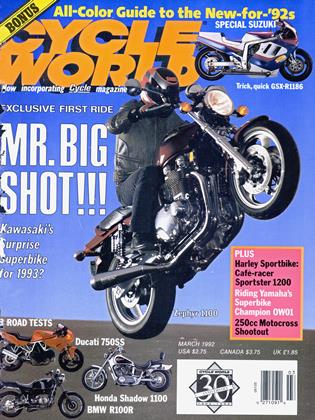

It’s in the standard-bike category, though, where I see the most room for improvement. Fast year's Honda Nighthawk 750 and Kawasaki Zephyr 750 were positive moves, but this month’s coverbike Zephyr 1100 is more like it. Fifty-cc step-throughs and 305 Super Hawks notwithstanding, the two bikes that put Japan on the motorcycle map in the U.S. were the ’69 Honda CB750 and ’73 Kawasaki Z1. These were big, powerful machines that could be (and were) used for everything from roadracing to 1000mile days on 1-40. The Zephyr 1100 brings back that versatility. In fact, in designing the Zephyr series, Kawasaki sent a team of engineers across America to gather notes from owners of old Z-ls and KZ 1000s.

Honda, too, has a big-bore yesterbike in the wings. Called the CB1000 Super Four, it emulates owner-modified CB750/900FS, which, in turn, emulated AMA Superbikes of the late ’70s and early ’80s.

If there is a drawback to bikes like the big Zeph and the CB1000, though, it’s in their retro-styling, which is as popular in Japan as rice cakes and raw fish, and is poised to take Europe by storm, too. But I'm not so sure there’s a large segment of U.S. riders who want motorcycles that are basically caricatures of the machines we customized in our backyards 10 and 15 years ago.

There are a couple of current standard-style bikes that are more modern in styling and componentry, but they lack size-in both engine displacement and chassis dimension. One is Honda’s 400cc CB-1, the Best Fittle Bike That Nobody Bought; unsold 1989 models are still for sale at sizable discounts. Good looking, with its inline-Four mounted in a round-tube frame, with up-todate brakes and tires, and with modern single-shock rear suspension, the CB-1 was impressive, but it didn’t play very well in Peoria.

Suzuki’s Bandit 400 is close in specification to the CB-1, but has been more successful, selling in relatively good numbers and even copping Cycle World's Best Under500cc Streetbike award last year, due to its sub-$4000 price and stunning scarlet paint job. I knew Suzuki had popped one into the centerfield bleachers with the 400’s styling when I pulled up outside a classic-bike shop on our test Bandit, and promptly emptied the joint. Everyone thereeven the resident Harley guy-gave the bike a big thumbs-up.

But although the CB-1 and Bandit are excellent bikes, both are hampered here because they were designed primarily for the Japanese market. The average American is cramped on either one; and while wringing an engine to 14,000 rpm can be exhilarating, most of us prefer the wallop-in-the-seat sensation that a torque-heavy motor gives.

Simple solution, though: Stretch each bike a few inches in every direction, and drop in 600 (good), 750 (better) or llOOcc (now we’re talking) motors. Keep the price in line, and, presto, instant new American standard, a bike that I-and, I’m guessing, a good many others-would buy.

At least one manufacturer agrees with me. Yamaha’s new Seca II, a 600, is just such a model, and is good enough that it won last month’s Bargain Blasters comparison test. If the Seca sells well-and I believe it will-we just may see responses in kind from the rest of the industry.

And let’s not worry so much if these bikes sacrifice some top-end horsepower for midrange oomph. There are Ninjas and GSX-Rs and CBRs and FZRs for those interested in outright performance. I’d even argue that part of the appeal of those early CB750s and Z-ls was that owners could easily boost their bikes’ performance levels, which led to ongoing relationships between man and machine-not to mention a healthy aftermarket business. But unless you’re prepared to do stem-to-stern modifications, messing with today’s high-performance sportbikes usually only makes them noisier, slower or less reliable. Fikely all three.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ve got a spare half-hour, and the BSA needs a little exercise. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue