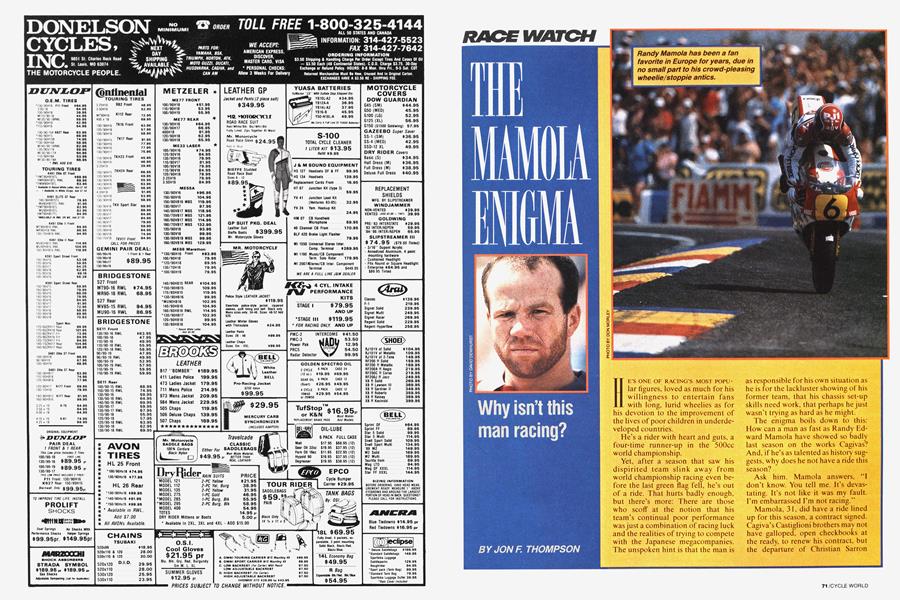

THE MAMOLA ENIGMA

RACE WATCH

Why isn't this man racing?

JON F. THOMPSON

HE'S ONE OF RACING'S MOST POPUlar figures, loved as much for his willingness to entertain fans with long, lurid wheelies as for his devotion to the improvement of the lives of poor children in underdeveloped countries.

He’s a rider with heart and guts, a four-time runner-up in the 500cc world championship.

Yet, after a season that saw' his dispirited team slink away from world championship racing even before the last green flag fell, he’s out of a ride. That hurts badly enough, but there’s more: There are those who scoff at the notion that his team’s continual poor performance was just a combination of racing luck and the realities of trying to compete with the Japanese megacompanies. The unspoken hint is that the man is as responsible for his own situation as he is for the lackluster showing of his former team, that his chassis set-up skills need work, that perhaps he just wasn't trying as hard as he might.

The enigma boils down to this: How can a man as fast as Randy Edward Mamola have showed so badly last season on the works Cagivas? And, if he’s as talented as history suggests. w'hy does he not have a ride this season?

Ask him. Mamola answers, “I don’t know. You tell me. It's devastating. It’s not like it was my fault. I’m embarrassed I'm not racing.”

Mamola, 31, did have a ride lined up for this season, a contract signed. Cagiva’s Castiglioni brothers may not have galloped, open checkbooks at the ready, to renew his contract, but the departure of Christian Sarron from the first-string Yamaha of France’s Sonauto Racing left a vacancy there. Sonauto was eager to fill it with Mamola. But Sonauto based its offer on the promise of sponsorship from Gauloises, a tobacco company that withdrew its support of motor racing in December after the French government, newly concerned about the effects of tobacco use. outlawed tobacco advertising. No sponsorship, no budget, no money with which to honor the newly minted Mamola contract. By the time the French government promulgated its ruling, all the other 500 GP teams had their riders.

An offer to race 250s came from Aprilia, but Mamola rejected it. He explains. “They offered me a lot of money, but money’s never driven me. I love the sensation of speed, and 250s just don't appeal to me."

So. when the GP riders dropped their clutches at the beginning of this season in Japan. Mamola was left standing in the paddock, frozen out of a ride by a twist of politics, timing and luck.

Oh yes. Mamola believes in luck.

He says, "I know how much luck there is in racing. For instance. Kevin Schwantz is the fastest guy on the track. But he hasn't had the luck."

For those who suggest that perhaps Mamola wasn’t giving 100 percent last year, that he could have made his own luck by trying harder, he has just one word: "Bullshit! If you do something 95 percent, you're not doing your job. The fact is that I've never won a world championship. I'd have liked to have won one, but each year I finished second in the standings—'8 1 and '82 on the Suzuki, '84 on the Honda and '87 on the Yamaha—I've tried my hardest. I've no regrets."

Why, then, has the (’agiva. the beautiful red rocket that has had so much money thrown at it. never won a GP race, never even become a fro n tran k con t e n d e r?

There have been chassis problems. solved now. at least partially, by massive help from outside companies such as Ferrari—and, some say, from the Japanese motorcycle manufacturers.who are interested in giving the GPs a continental flavor, interested in not making the series an all-Japan show. There have been engine problems. solved now. at least partially, some suggest, by help from Yamaha technicia ns.

There have been problems with team politics, and these have been less easy to solve. Mamola presents an example of those politics: “The engine builder at the factory, he was mechanic for both Renzo Pasolini and Giacomo Agostini. He took care of the Castiglioni brothers when they were kids. It was hard to go around him with engine problems."

And there were supply problems, particularly when the Cagiva team tried to source components from Japan. Mamola says. “We tried to get ignition and carburetor parts from Japan last year. The Japanese companies gave preference to the Japanese teams. We were put at the end of the list. It was very frustrating."

All these problems so impeded development of the V590. last year's Cagiva GP bike. Mamola says, that its top speed was 15 miles per hour slower than the top speeds of the fastest bikes. He adds, “At Assen (site of the Dutch TT), from the last turn to the start/fînish line, we were a halfsecond slower on acceleration than the front-running bikes."

The one time last year the V590 was competitive was at the Belgian GP. where a wet track minimized the differences between racebikes and maximized the effect of a rider's skill. Here, after starting eighth. Mamola pressed his luck, tires and ability to work his way up to third. And then he crashed out. That ride, along with his ride in the 1990 USGP. where he finished seventh after dislocating his left wrist in a nearhigh-side so violent that it punched his head and shoulders through the bike's windscreen, testifies in favor of Mamola's contention that he always rode as hard as he could.

Looking back at the season. Mamola shrugs helplessly and says.

“I worry that I was too loyal, not walling enough to criticize people I respected. I didn't want to tell my mechanics that my bike, the machine they'd built, was a piece of shit. How would that have made them feel? It was frustrating. A lot of times I wanted to cry. I was trying so hard to keep up the image of our team . . ..”

The team’s image took a drubbing, especially from the European media, at the Dutch TT. A sighting-lap wheelie went wrong, putting the Cagiva over backwards. Repairing the damage made Mamola late for the start. Though he had qualified eighth, he finished 18th, the final runner. According to the Euromedia, the Castiglionis were furious.

But Mamola says the brothers understood the tip-over was just a racing incident: "I was late coming out onto the track. Nobody believes it, but when I wheelied and went to correct, the throttle locked open. There was nothing I could do.”

However the Castiglionis may have felt about that incident, when Mamola was told that Cagiva was leaving racing before the end of the 1990 season, and that his contract would not he renewed, he says he managed to cement a warm relationship with them.

Still, damage was done. According to Claudio Castiglioni, who manages the Cagiva GP team. “When Mamola really commits himself, he can ride beautifully. But his performances during l 989 and '90 were not consistant. In every team there is a time when change is necessary.”

Castiglioni recognized that Mamola rode while injured, but he added, “The bike, the rider, the team—all these elements must come together for a successful season. We have great respect for Randy

Mamola and we are grateful to him for what he did while riding for us. But we have to consider the results, and these are in favor of (Eddie) Lawson. He is playing a fundamental role . . . he pushes hard to reach the

goals the team sets. The results so far prove it. Our only problem will be finding someone who can perform as well when he quits.”

Indeed, a prime factor that kept Cagiva in GP racing was the signing of Lawson, a four-time world champion known for his development and set-up abilities. Mamola says of the Cagiva pursuit of Lawson, “Last year, they asked me to try to get Eddie to ride with me as a teammate. Eddie said he'd never ride the Cagiva.”

One reason for Lawson's reluctance. Mamola theorizes, is that “The guys used to laugh at me when they'd pass. They didn't even have to draft me. They all knew what I was fighting.”

He says of Lawson’s sixth-place finish in the USGP aboard the Cagiva V59l, “Hey. Barros (Lawson's Cagiva teammate) caught him and passed him at Laguna Seca. Yeah. Eddie eventually passed him back, but Barros never did that to me. Eddie finished sixth, but if Nial I Mackenzie. Christian Sarron and I had been there, he might have been ninth. I'm not saving I'm better than Eddie. But I know I'm as good.”

Lawson, in Europe for the grand prix season, was unavailable for comment, though it should be pointed out that he placed third at the Italian GP two weeks after Cycle World inter-

viewed Mamola, with Barros finishing in fourth place.

If Mamola has faith in his abilities, so, apparently, do the few GP team managers he has talked with about filling in on spare bikes. Mamola says of one of' the stronger possibilities, “(Sito) Pons has broken his shoulder (in a testing accident prior to the Spanish GP); he’s out until the Dutch IT. Campsa (which sponsors Pons' Honda) wants a rider, and I'm open to it. But Honda doesn't want to rush into a replacement for Pons. So. it's on hold. Campsa knows I'm interested. I do want to race, but 1 don't really believe I'm a replacement rider. My ability is worth a hell of a lot more than that.”

So, if the right deal doesn’t come through. Mamola will content himself with blitzing the hills near his Santa Clara. California, and Incline Village, Nevada, homes aboard his Ducati 851, with cruising around on one of his Harleys, or with tooling around in one of his classic and exotic cars. He also busies himself with his ongoing efforts to raise funds for his favorite charity. Save The Children. about which he says. “I haven't got a ride, but these kids in Sudan and Somalia, they've got nothing, not even food.” He’ll also work on putting together a racing program for next year. Grand prix, he hopes. If that doesn't work, maybe World Superbike. About that, he says, “It'd have to be competitive. I can't be riding a Vespa. I'd retire before I'd tarnish my name.”

Not that Randy Mamola is eonsid-

ering retirement. That will come, he says, “Only when I don’t enjoy it. Right now, I enjoy the inside and outside of racing.”

Asked if he’s set financially. Mamola frowns and says, “Well, yes and no. If you earn a lot of money.

you have to pay a lot of taxes. I’m not as able to keep up with my hobbies as well as I might like, but, no, I don’t have to work.’’ Then he adds, “But I want to.”

The work Mamola will try for, the work he knows best, is, as they say, nice work—if he can just get it. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSpeed Thrills

August 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeStatus Miles

August 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

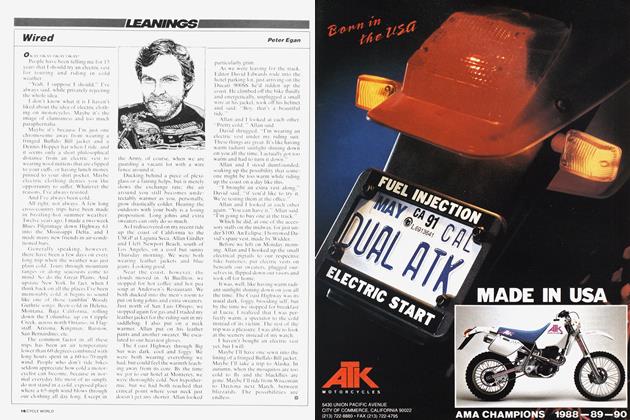

Leanings

LeaningsWired

August 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1991 -

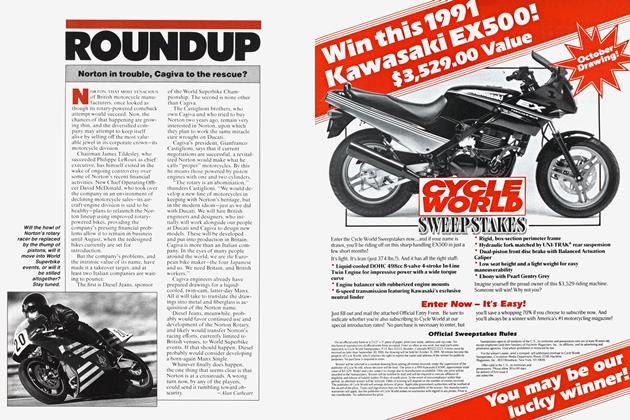

Roundup

RoundupNorton In Trouble, Cagiva To the Rescue?

August 1991 By Alan Cathcart -

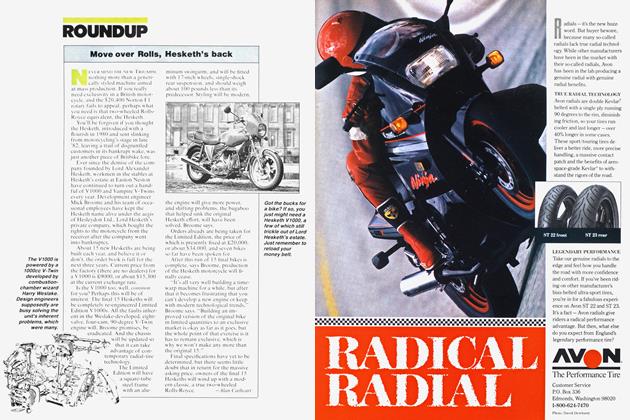

Roundup

RoundupMove Over Rolls, Hesketh's Back

August 1991 By Alan Cathcart