Wired

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

OKAY OKAY OKAY OKAY! People have been telling me for 15 years that I should try an electric vest for touring and riding in cold weather.

"Yeah, I suppose I should,” I've always said, while privately rejecting the whole idea.

I don't know what it is I haven’t liked about the idea of electric clothing on motorcycles. Maybe it's the image of clumsiness and too much paraphernalia.

Maybe it's because I'm just one chromosome away from wearing a fringed Buffalo Bill jacket and a Dennis Hopper hat when I ride, and it seems only a short philosophical distance from an electric vest to wearing wool mittens that are clipped to your cuffs, or having lunch money pinned to your shirt pocket. Maybe electric clothing denies you the opportunity to suffer. Whatever the reasons. I’ve always resisted.

And I've always been cold.

All right, not always. A few long cross-country trips have been made in broiling-hot summer weather.

1 welve years ago, I made a two-week Blues Pilgrimage down Highway 61 into the Mississippi Delta, and I made many new friends in air-conditioned bars.

Generally speaking, however, there have been a few days on every long trip when the weather was just plain cold. lours through mountain ranges or along seacoasts come to mind. So do the Great Plains. And upstate New York. In fact, when I think back on all the places I've been memorably cold, it begins to sound like one of those ramblin' Woody Guthrie songs: Been cold in Helena, Montana, Baja (alifornia. rolling down the Columbia, up on ( ripple Creek, across north Ontario, in I'laiistaff. Arizona. Kingman. Barstow. San Bernardino, etc.

flic common factor in all these trips has been an air temperature lower than 60 degrees combined w ith long hours spent in a 6()-to-70-mph wind. People who don't ride bikes seldom appreciate how cold a motorcyclist can become, because in normal everyday life most of us simply do not stand in a cold, exposed place where a 65-mph wind blows through our clothing all day long. Except in

the Army, of course, when we are guarding a vacant lot with a wire fence around it.

Ducking behind a piece of plexiglass or a fairing helps, but it merely slows the exchange rate; the air around you still becomes undetectablv warmer as you, personally, grow' drastically colder. Heating the outdoors with your body is a losing proposition. Long johns and extra sweaters can only do so much.

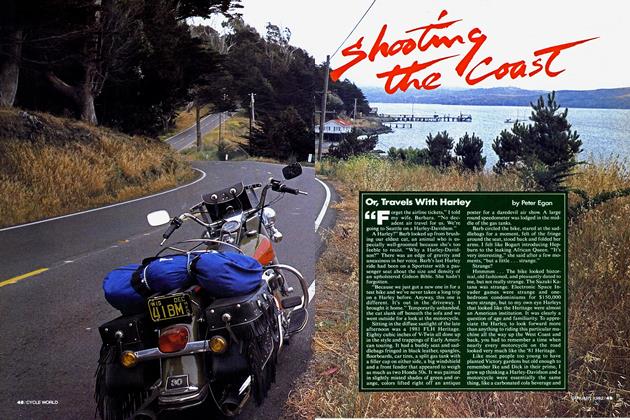

As I rediscovered on my recent ride up the coast of California to the USGPat Laguna Seca. Allan Girdler and I left Newport Beach, south of Los Angeles, on a cool but sunny I hursday morning. We were both wearing leather jackets and blue jeans. I .ooking good.

Near the coast, however, the clouds moved in. At Buellton, we stopped for hot coffee and hot pea soup at Andersen's Restaurant. We both ducked into the men's room to put on long johns and extra sweaters, .lust north of San Luis Obispo, we stopped again for gas and I traded my leather jacket f or the riding suit in my saddlebag. I also put on a neck warmer. Allan put on his leather pants and another sweater. We escalated to our heaviest gloves.

I he Coast Highway through Big Sur was dark, cool and foggy. We were both wearing everything we had. but could feel the warmth leaching away from its core. By the time we got to our hotel at Monterey, we were thoroughly cold. Not hypothermic. but we had both reached that critical point where your neck just doesn't get any shorter. Allan looked

particularly grim.

As we were leaving for the track. Editor David Edwards rode into the hotel parking lot. just arriv ing on the Ducati 900SS he'd ridden up the coast. He climbed off the bike fluidly and energetically, unplugged a small wire at his jacket, took off his helmet and said. "Boy. that’s a beautiful ride.”

Allan and I looked at each other. "Pretty cold, ” Allan said.

David shrugged. "I'm wearing an electric vest under my riding suit.

I hese things are great. It's like having warm radiant sunlight shining down on you all the time. I actually got too warm and had to turn it down.”

Allan and I stood dumfounded, soaking up the possibility that someone might be too warm while ridimz up the coast on a day like this.

"1 brought an extra vest along,” David said, “if you'd like to try it. We're testing them at the office.”

Allan and I looked at each other again. "You can have it.” Allan said. "I'm going to buy one at the track.”

Which he did, at one of the accessory stalls on the midway, for just under $ 100. An Eclipse. I borrowed David's spare vest, made by Widder.

Before we left on Monday morning. Allan and I hooked up the small electrical pigtails to our respective bike batteries, put electric vests on beneath our sweaters, plugged ourselves in. flipped down our v isors and took off for home.

It was, well, like having warm radiant sunlight shining down on you all the time. I he ('oast Highway was its usual dark, foggy, brooding self, but by the time we stopped for breakfast at Lucia. I realized that I was perfectly warm, a spectator to the cold instead of its victim. The rest of the trip was a pleasure. I was able to look at the scenery instead of my watch.

I haven't bought an electric vest yet. but I will.

Maybe I'll have one sewn into the lining of a fringed Buffalo Bill jacket. Maybe I'll take a trip to Alaska. In autumn, w hen the mosquitos are too cold to fly and the blackflies are gone. Maybe I'll ride from Wisconsin to Daytona next March, between blizzards. The possibilities are endless. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSpeed Thrills

August 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeStatus Miles

August 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1991 -

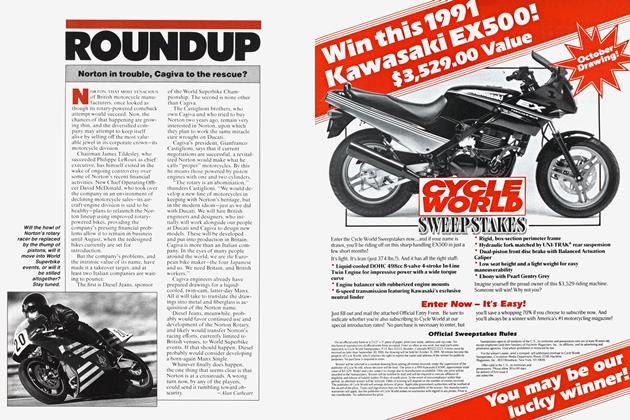

Roundup

RoundupNorton In Trouble, Cagiva To the Rescue?

August 1991 By Alan Cathcart -

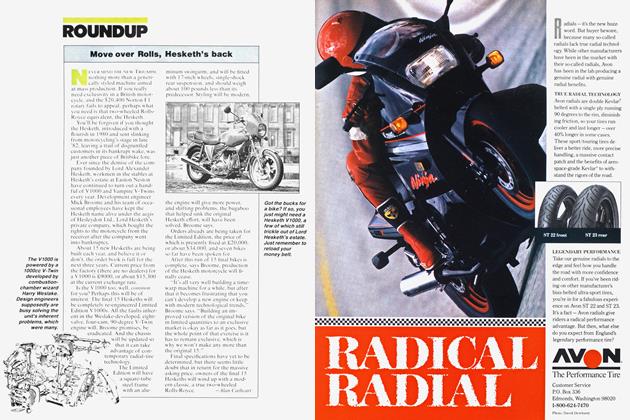

Roundup

RoundupMove Over Rolls, Hesketh's Back

August 1991 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupQuick Ride

August 1991 By Jon F. Thompson