FORMULA FOR SUCCESS?

RACE WATCH

Taking Formula USA into the big time isn’t going to be easy for WERA. But battling the AMA for control of roadracing in America will be even harder

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

BARRELING TOWARD WILLOW Springs' infamous Turn Eight at over 140 miles per hour, the pack of 50 motor-

cycles begins to string out a little. Midway through the long, top-gear sweeper, a crisp, orange-and-white Yamaha TZ250 buried deep in the swarm begins passing heavily modified Suzuki GSX-R1100s and Yamaha FZR1000s on the outside, blowing past the bikes two and three at a time. Once on the front straight, however, the bellowing bigger bikes regain their positions, only to be passed again in the next corner by the smaller two-stroke.

This is not a weird practice session with bikes of all sizes and configurations lumped together: it’s the kickoff race of the Western Eastern Roadrace Association’s (WERA) Formula USA series. F-USA is a runwhat-ya-brung, unlimited racing class, the brainchild of Bill Huth. owner of the Willow Springs track in Rosamond, California. About the onlv rule is that bikes have to run on gasoline, though turbocharging and nitrous-oxide injection are perfectly acceptable means of increasing horsepower. This leads to a crazy mix of motorcycles, with 250cc twostrokes at the one end. GSX-R 1 100s with nitrous oxide at the other.

Last year. Huth expanded the series and sent F-USA on the road under the control of WERA. So far. WERA and F-USA have proven to be a perfect match, the series gaining in prominence as WERA evolves from a club-level organization toward a more-professional roadrace sanctioning body. As a measure of WERA's maturity, it offers more money for its Formula USA championship than does the AMA for its Superbike crown.

What's more. WERA and the FUSA series got a big boost in sponsorship this year, helped bv the fact that all 10 races of the series will be televised on the Prime Ticket cable network. WERA officials believe television is a key requirement if its road racing program is to grow from an amateur sport to a top-level professional venture where riders, teams and sponsors can make more money than they spend. And it was this television coverage which also helped to draw some of America's top teams and racers to the opening event, and which will allow WERA to compete with the AMA's Superbike series for participation of the sport's big names.

That WERA is having a bit of success in luring away some of those top teams was evident at the Willow event when Kenny Roberts' U.S. Team Marlboro 250 team showed up, as did the Vance & Hines/Yamaha and Yoshimura/Suzuki teams. On top of that. Roberts had just notified the AMA that he was pulling his bikes out of the AMA's 250 GP class entirelv and had committed full-time to the WERA F-USA series. Indeed, for 1990. Roberts intends to back WERA as much as he can. “We wanted to do this (compete in WERA events) eventually, and it just so happened that this was the time to do it. I will personally do everything I can to help these guys." says Roberts of the WERA organization. “I'll try to be at as many of the races as I can, and my team will definitely be there."

Roberts' split with the AMA reflects a growing dissatisfaction many racers have with the way that organization runs its roadracing program. Most of the top teams believe that if

roadracing in America is to grow the way so many other motorsports have in recent years, it will need an infusion of money from outside sponsors. But the AMA has not been able to secure television exposure for roadracing, and doesn’t even have a current Superbike series sponsor. Which means that the AMA has to make its money from sanctioning fees, and by charging racers and teams high prices for entry fees and pit passes. Says Rob Muzzy, owner of Team Muzzy/ Kawasaki, “I think we’re on the verge of making roadracing a real show. But if the AMA can’t do it, we need to look at other ways of getting that accomplished. In the meantime, our team will race wherever the competition is.”

What ultimately spurred Roberts to bail out of the AMA, however, was not its inability to move roadracing into the “big time;” instead, it was that association’s controversial demand that all riders put a large, “AMA Pro Racing” patch on the upper left-front area of their racing leathers. Roberts refused, explaining that this part of a rider's uniform is considered a high-visibility area that

the teams sell to sponsors at premium prices. Complying with the AMA's requirements could, therefore, cost a team a significant amount of potential revenue. “I can’t sell sponsorship if I have to give away prime space for free,” says Roberts. “Also, I could afford to lose a sponsor if I had to,

but what about the little guy who’s barely making it? How is he going to make money if he has to remove a paying sponsor’s patch in order to give that space to the AMA?”

Ron Zimmermann, the AMA’s vice-president of professional competition, says the AMA is not happy that Roberts has decided to take his racing elsewhere, but adds, “Roberts has achieved more success than any other racer in American history, and a lot of that success came as a result of his days with the AMA. So, it’s interesting to me that he dislikes us so much.” Zimmermann also dismisses criticism of AMA racing policies from other riders, even one as accomplished as two-time AMA Superbike champion, two-time AMA 250 champion and four-time world 500 GP champion Eddie Lawson, who believes the AMA does great work in politics but should leave racing alone. Zimmerman says, “Being the best racer in the world does not mean you know anything about racing. Anyone can throw stones, but it’s harder to come up with solutions.” Though Roberts has believed for a long time that things are not likely to change for the better with the AMA, he did not reach his decision to leave easily or quickly. “Eve been a big supporter of the AMA 250 GP class.

In fact, when I thought the class was going to disappear, I told Yamaha 1 would bring in 250s myself and sell them if they wouldn't do it. Now, I have no say in how the AMA runs things. I'm just like a paying spectator in that regard. And like spectators, the only thing I can do if I don’t like what I see is to not go. So I'm not going.”

Muzzy echoed Roberts’ sentiments. “When we tell the AMA what we don't like, they tell us if we don’t like it. don't come. But right now, I don’t have the luxury of pulling out like Roberts did.”

So, the Roberts team will be going to WERA races from now on, and that means there will have to be some changes. The team’s talented rider, Rich Oliver, can make the TZ250 competitive on tighter tracks, but at courses like Willow Springs, with its high-speed corners, long straights and seemingly ever-present wind, Oliver just doesn't have enough bike beneath him to win against the megahorsepower GSX-RllOOs and FZRlOOOs that make up most of the entries in the F-USA class. There are rumors that Team Roberts will find a 500 gran prix bike for Oliver before the year is out.

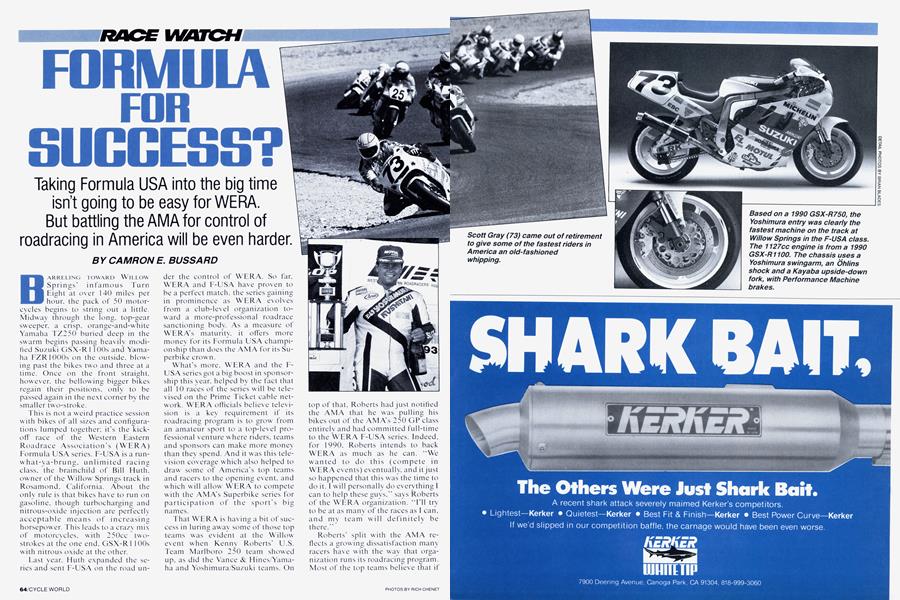

For now, however, the Suzuki that was ridden at Willow by Scott Gray is the model for the class. After sitting out most of last season. Gray showed up on a l 70-horsepower, Yoshimuraprepared, GSX-R l l 00-powered monsterbike. And although Gray may be leaner than in previous seasons, at just under six feet tall and 200 pounds, he still hulks over his motorcycle and rides it with the zeal of a Viking plundering a village.

But the truth is. Gray is one of the fastest racers in America today, though some say the most dangerous, as well, pointing to his long history of spectacular and harrowing crashes. Nonetheless, the wide-open F-USA is a series custom-tailored to Gray, and the Yoshimura-built Suzuki is the perfect weapon for him. He had >

spent the better part of a month testing the bike, and says, “It was set up perfectly. I love to ride it because it’s so awesome.”

That was, as they say, no brag, just fact: Gray set a track record of 1:25.9 in the morning practice session before the race, breaking his old record of 1:26.1.

Gray was not alone in blazing around Willow's nine-turn circuit. Team Suzuki Endurance rider Mike Smith had his GSX-R1100 going faster each session, turning times in the mid-27s and closing in on Gray, who was consistently in the mid-26s.

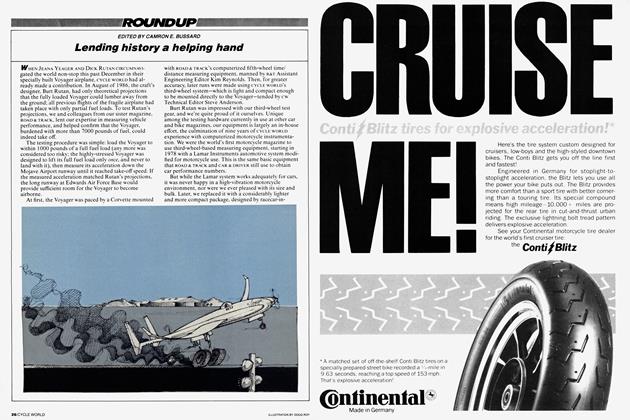

Smith’s Suzuki looked much like Gray's Yoshimura bike, but a quick examination proved it to be quite different. Smith’s bike was set up primarily for endurance racing, though for the F-USA competition, a hotter engine was installed in the 1 100 chassis. The Yoshimura bike, on the other hand, was an AMA 750 Superbike chassis that had been stuffed with a modified GSX-R1 100 engine just for this race.

Then there was the Vance & Hines Team of Daytona 200 winner Dave Sadowski and Thomas Stevens, who were in the 1:27 range on a pair of matching, factory-supported Yamaha OWOl 750s. Privateer Barry Burke was Yamaha-mounted, too, but he is still in the midst of building what he thinks will be the ultimate FUSA bike: a fuel-injected FZR1000 engine slipped into an OWOl chassis. For the opening round at Willow, Burke rode a ratty looking, but deceptively fast, 1987 FZR1000.

But the bike everyone was most curious about belonged to Don Canet. With the help of the people at Nitrous Oxide Systems, Canet had set up his 1 100-powered GSX-R750 with nitrous injection, which he thought would give tremendous drive out of the corners and blazing speeds on the straights. But despite weeks of non-stop work and many sleepless nights, Canet ran out of time before successfully working out all the kinks, leaving unanswered the question of whether or not his idea will be practical in the horsepower wars that make F-USA racing so exciting.

As it turned out, most of the drama occurred before the race, because once the flag dropped, Gray ran off and hid from the other racers. He dominated from the start, quickly jumping out to a comfortable, 1 1second lead that was never threatened. “They told me to take it easy,“ he said, “but I can’t do that.” Behind Gray, the Vance & Hines riders engaged in a dramatic, two-bike duel, with Sadowski drafting past Stevens at the checkered flag to take second.

Mike Smith charged from a 23rdrow start (his GSX-R had quit in the qualifying heat) and worked his way up to sixth position, with Rich Oliver on the TZ250 tucked in behind him. “I thought I was in that SEGA ‘HangOn’ video game, there were so many riders out there I had to pass,” Smith said. At the end. Smith managed to get away from Oliver and steal fifth position from Chuck Graves, but he was unable to catch Burke for fourth.

Even though the Willow Springs event was the first F-USA race of the season, it was probably not an accurate indication of things to come. As of the time we went to press, Gray had no plans to race any of the other events. Because of a strange set of circumstances, Gray, the 1988 F-USA champion, doesn’t have a contract to race; and even though he does get the occasional ride from Yoshimura, that team is not budgeted to race the FUSA series due to its full commitment to AMA Superbike racing.

Neither will the Vance & Hines team be competing in any more of the WERA events, also because of its commitment to the AMA Superbike > schedule. Other Superbike teams, notably Team Muzzy/Kawasaki and the Commonwealth Honda team, would like to race some WERA events, but simply cannot afford to compete in two series. The Kawasakis will, however, show up at one or two of the FUSA races.

So, in the end. Willow was little more than a warm-up, a chance for the racers to gauge each other and sort out their no-holds-barred machinery. But the success of the race and the enthusiasm of everyone involved gave a lot of momentum to the series. “I could tell no difference

between this race and an AMA event," said Roberts. “My rider is happy and the team is satisfied. What more can I ask?"

1 hat’s a pretty strong endorsement from one of the most-influential men in racing. And, of course, the AMA’s loss is WERA’s gain, as the addition of Team Roberts will lend even more credibility to the organization that wants to become this country’s premier roadracing association. If many more top teams defect to WERA, the AMA will either have to restructure its program or risk losing more than just the top professional racing teams. It could quickly become something it has never before been: America’s second-string roadrace sanctioning body. ©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

August 1990 -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

August 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

August 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupBimota-Guzzi: High-Tech Chassis Meets Low-Tech Motor

August 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupHonda Prices: What Was Up Goes Down

August 1990 By Jon F. Thompson