Gilera CX

CW RIDING IMPRESSION

Another Exotic Italian

IN AMERICA, DUCATI MAY BE THE quintessential Italian marque, but in Europe, there exists plenty of competition for that honor, especially in the small-bore classes so beloved by Euro-riders.

One such competitor is Gilera, which since its founding in 1909, has developed not only a rich and varied racing heritage (see “The Glory of Gilera,” page 65), but a clear vision for the future. The Gilera CX is at once a loud, clear echo of that heritage and at the same time, in a form as modern as a space shot, one of the first fruits of Gilera’s revitalized vision and vigor.

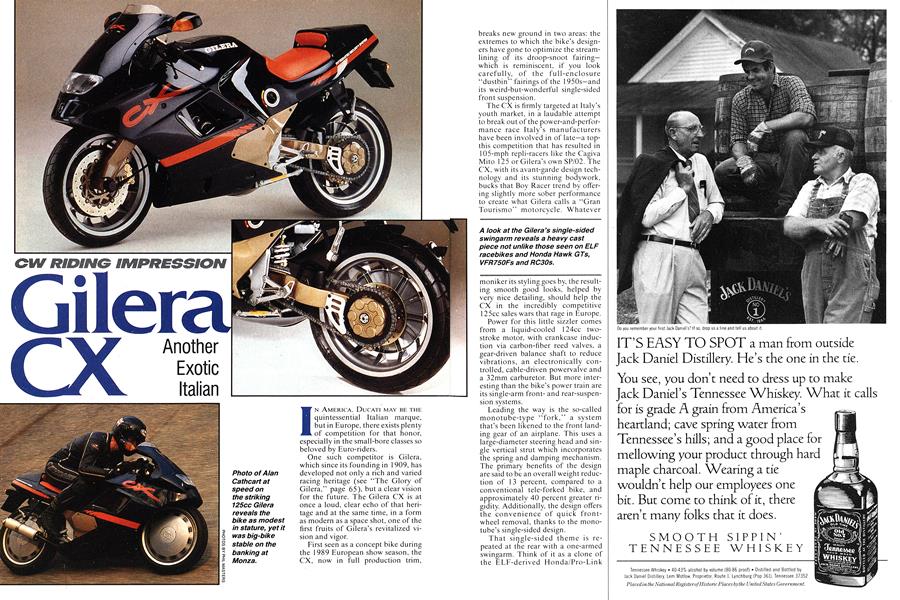

First seen as a concept bike during the 1989 European show season, the CX, now in full production trim, breaks new ground in two areas: the extremes to which the bike’s designers have gone to optimize the streamlining of its droop-snoot fairing— which is reminiscent, if you look carefully, of the full-enclosure “dustbin” fairings of the 1950s—and its weird-but-wonderful single-sided front suspension.

The CX is firmly targeted at Italy's youth market, in a laudable attempt to break out of the power-and-performance race Italy’s manufacturers have been involved in of late—a topthis competition that has resulted in 105-mph repli-racers like the Cagiva Mito 125 or Gilera’s own SP/02. The CX, with its avant-garde design technology and its stunning bodywork, bucks that Boy Racer trend by offering slightly more sober performance to create what Gilera calls a “Gran Tourismo” motorcycle. Whatever

A look at the Gilera’s single-sided swingarm reveals a heavy cast piece not unlike those seen on ELF race bikes and Honda Hawk GTs, VFR750FS and RC30s.

moniker its styling goes by, the resulting smooth good looks, helped by very nice detailing, should help the CX in the incredibly competitive 125cc sales wars that rage in Europe.

Power for this little sizzler comes from a liquid-cooled 124cc twostroke motor, with crankcase induction via carbon-fiber reed valves, a gear-driven balance shaft to reduce vibrations, an electronically controlled, cable-driven powervalve and a 32mm carburetor. But more interesting than the bike’s power train are its single-arm frontand rear-suspension systems.

Leading the way is the so-called monotube-type “fork,” a system that’s been likened to the front landing gear of an airplane. This uses a large-diameter steering head and single vertical strut which incorporates the spring and damping mechanism. The primary benefits of the design are said to be an overall weight reduction of 13 percent, compared to a conventional tele-forked bike, and approximately 40 percent greater rigidity. Additionally, the design offers the convenience of quick frontwheel removal, thanks to the monotube’s single-sided design.

That single-sided theme is repeated at the rear with a one-armed swingarm. Think of it as a clone of the ELF-derived Honda/Pro-Link system—which likely will keep the patent lawyers busy for some while.

Braking is accomplished via a single 1 1.8-inch disc up front and a 9.4inch disc at the rear. The bike, with its compact, 53.9-inch wheelbase, rides on wide, 17-inch Pirelli radiais—the front rubber is a 120/60, the rearan incredibly chunky 150/60.

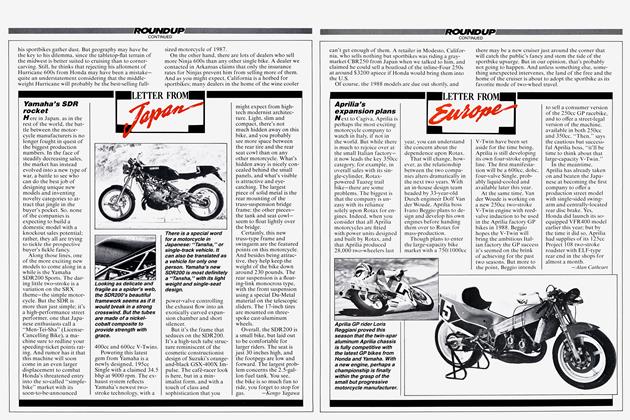

How’s it all work? To find out, we made our way onto the historic and unbelievably bumpy banking of the historic Monza Autódromo, which hasn’t been used in almost 20 years. In spite of its 265-pound feather-

weight build and the relatively short travel of the suspension —3.9 inches at the front, 5.3 inches at the rear— the CX was surprisingly stable and comfortable over the roughness, the rising-rate rear end feeling especially responsive and giving the ride of a bigger bike, in turn reinforcing the CX’s aura of sophistication.

And out in the world of real roads and real traffic, the CX was equally impressive. For a start, the engine makes the bike very easy to ride, and speeds of 100 mph should be attainable given the slippery shape of the CX’s bodywork. A relatively short stroke helps engine acceleration, and the electronic powervalve opens at 7800 rpm for a hefty but controllable boost in performance. Peak power is produced at 10,500 rpm, but the engine runs readily up to 12,000 before power tails off.

The front end is very responsive, and transmitted road feel very well. This is one of the big advantages of such a direct steering system versus a center-hub system with its various linkages—you can really feel what the front tire is telling you.

The CX’s riding position is superb. Though the footrests are relatively high and aft-mounted, the seat and bars are high enough to provide a comfortable stance. Coupled with the carefully sculpted fuel tank, the result is a really well thought-out riding position that justifies the GT classification. The car-type dash is comprehensive, and numerous styling touches, such as the integrated, mirrors and turnsignals, are the work of a master designer.

As interesting as all this is, what’s even more interesting is that this little rocket is much more than some techno-artistic exercise. The CX was scheduled to be in Italian dealers’ showrooms by April, so by the time you read this, examples should be blitzing European backroadsthough at this writing, a price for the CX had not yet been announced.

The message is unspoken, but clear: The CX represents the first in a family of new Güeras of similar unconventional design—and with luck, these will possess the multi-cylinder, four-stroke engine that a full GT concept really requires.

Güera can’t afford otherwise. And with the influence and expertise of Federico Martini, late of Bimota but now chief engineer at Gilera, strongly behind the CX, we certainly wouldn’t bet against its süccess.

Alan Cathcart

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontDeath of the Fork?

May 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeTalking Hats

May 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1991 -

Roundup

RoundupMore Mini-Rockets From Japan

May 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupStrike Quiets Harley Plant

May 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupTrouble In Nortonland?

May 1991 By Jon F. Thompson