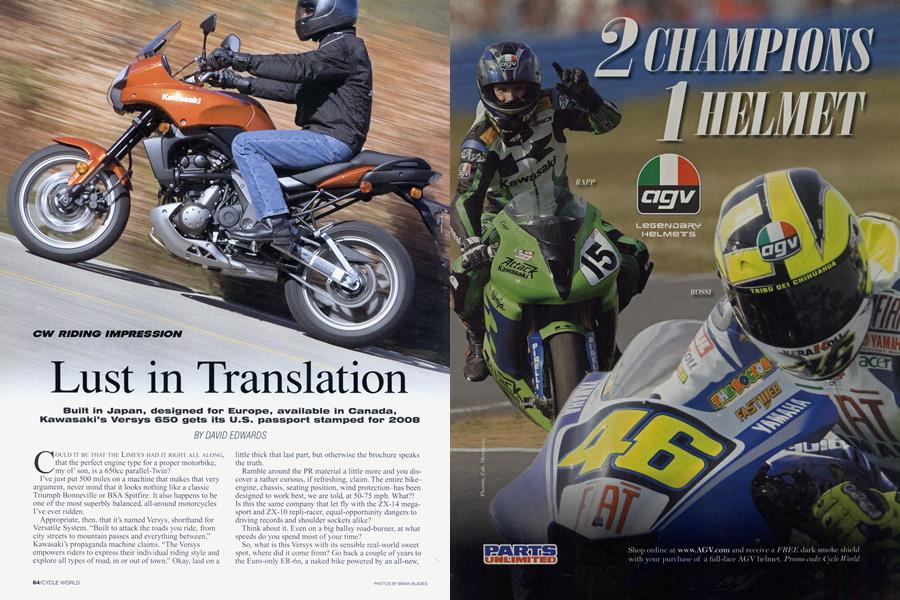

Lust in Translation

CW RIDING IMPRESSION

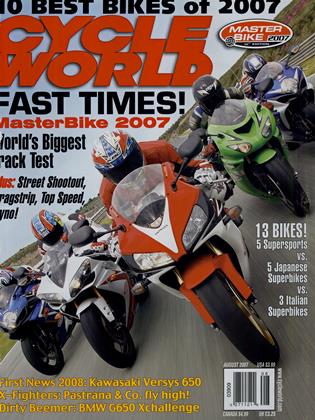

Built in Japan, designed for Europe, available in Canada, Kawasaki's Versys 650 gets its U.S. passport stamped for 2008

DAVID EDWARDS

COULD IT BE THAT THE LIMEYS HAD IT RIGHT ALL ALONG, that the perfect engine type for a proper motorbike, my ol' son, is a 650cc parallel-Twin?

I've just put 500 miles on a machine that makes that very argument, never mind that it looks nothing like a classic Triumph Bonneville or BSA Spitfire. It also happens to be one of the most superbly balanced, all-around motorcycles I've ever ridden.

Appropriate, then, that it's named Versys, shorthand for Versatile System. "Built to attack the roads you ride, from city streets to mountain passes and everything between," Kawasaki's propaganda machine claims. "The Versys empowers riders to express their individual riding style and explore all types of road, in or out of town." Okay, laid on a

little thick that last part, but otherwise the brochure speaks the truth.

Ramble around the PR material a little more and you discover a rather curious, if refreshing, claim. The entire bikeengine, chassis, seating position, wind protection-has been designed to work best, we are told, at 50-75 mph. What?!

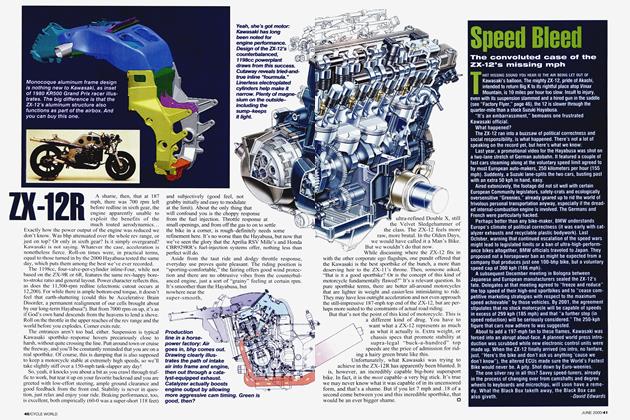

Is this the same company that let fly with the ZX-14 megasport and ZX-10 repli-racer, equal-opportunity dangers to driving records and shoulder sockets alike?

Think about it. Even on a big ballsy road-burner, at what speeds do you spend most of your time?

So, what is this Versys with its sensible real-world sweet spot, where did it come from? Go back a couple of years to the Euro-only ER-6n, a naked bike powered by an all-new, compactly built 649cc parallel-Twin. Narrower side-to-side than an inline-Four, shorter back-to-front than a V-Twin, a parallel-Twin makes for a very packageable powerplantwhich, of course is why it was the universal Britbike motor for so many years. This updated version had all your modern conveniences, though, like liquid-cooling, semi-downdraft fuel-injection with secondary butterflies, dohc, four valves per pot, under-piston oil jets, counterbalancer. Between the stacked transmission shafts and a semi-dry-sump lubrication system that stored scavenged oil in the transmission cavity away from the crankshaft (allowing a smaller, shorter crankcase), the engine was a tightly drawn, densely packed lump.

Smaller, even, than the Ninja 500’s, claimed Kawasaki.

Adding a full-fairing to this plot resulted in the ER-6f, thankfully rechristened Ninja 650R before making the move to America last year. We liked the bike a lot, calling it a, “Practical pleasure...a sensible, versatile motorcycle built for the sheer enjoyment of riding.” It’s been selling well for Kawasaki U.S., too, as an alternative to Suzuki’s previously unassailable SV650 V-Twin, and is even doing well at the racetrack, another SV stronghold.

If anything, the Versys is a better road bike than the Ninja. It takes the same engine package, re-cammed, recalibrated and with a slightly lower compression ratio (10.6:1 vs.

11.3:1 ) to accentuate the bike’s midrange-weighted mission statement. Our testbike, borrowed from Kawasaki Canada, spun the dials on CWs dynamometer to 58.8 rearwheel horsepower at 7600 rpm and 41.8 foot-pounds of torque at 6225 rpm. That’s about 3 hp less than the 650R with equal torque, though both figures arrive 1000 rpm lower in the rev range.

In fact, the Versys’ dyno chart is as nice as any we’ve seen lately, with diagonally rising power-no dips or spikes-from 2000 rpm to a peak plateau between 7500 and 9000 before tailing off as the 10,500-rpm redline hoves into view. Torque is equally user-friendly, its “curve” almost flat. Basically, anytime the engine is making noise, it’s producing between 30 and 42 foot-pounds.

On the road, that translates into immediate power and willing acceleration without a lot of downshifting, aided by spot-on fueling-far

from a given these days. Using the 650R as a performance yardstick, figure mid-12-second quarter-miles and a top speed of 115120 mph. Usefully sufficient.

Wrapped around the motor is the same basic type of steel, semi-perimeter, stressed-member main frame as used on the R. Also making the transition are the six-spoke, 17-inch cast wheels wearing sporty 120/70 front and 160/60 rear rubber. Likewise, the R’s wave-cut rotors and Tokico calipers-simple, two-piston jobs up front-are carried over.

Suspension, though, has been seriously upgraded. Gone is the Ninja’s non-adjustable conventional fork, replaced with an inverted unit that allows spring preload and rebound damping to be played with, the latter via a stepless adjuster atop the right-side tube. Travel is

increased from 4.7 to 5.9 inches. Anchoring the fork assembly is a black-anodized lower triple-clamp that looks stout enough for battle-tank duty.

At the other end we’ve said bye-bye to the 650R’s steel swingarm and hello to an asymmetrical aluminum structure with a massive gull-shaped right arm that serves as mounting point for the off-center, non-link Showa damper.

Said shock provides more travel than the R’s (5.7 inches vs. 4.9), has a seven-step preload ramp and two-stage damping adjustable over 13 settings.

Handling builds on the excellent, light-steering

qualities of the Ninja 650. The Versys, at 427 pounds dry measured on our scale, is 13 pounds heavier than its sportbike sibling, but its wider, higher handlebar gives it more leverage going into turns. Its 33.5-inch seat height is 2 inches up on the 650R saddle.

Those upright ergonomics take me back to my highschool days (shortly after the Earth cooled) when I was a

member of the varsity wrestling squad. The riding position is not unlike that taken by grapplers during face-offs. Weight over your feet, knees bent, arms up and wide, ready to respond to whatever your opponent-in this case the road, oncoming traffic, etc .-throws at you. There’s a strong sense of being in command. I don’t get that on repli-racers which have me leading with my head, never a good thing, or on cruisers that rotate my body back and jut my heels out front into the wind.

Location of the seat/footpeg/handlebar contact points approaches the ranginess of the late, lamented UJMs of the 1970s and early ’80s. Only thing missing is a seat that’s

ironing-board flat, pretty much an impossibility when you’ve got to make room for almost 6 inches of rear-wheel travel. Mounting up, shorter riders will have to hike their leg to clear the rear portion of the seat.

When it comes to styling, what to say? Even Kawasaki seems a little confused as to classification. On the U.K. website, the Versys is listed as a Dual-Purpose; in Germany,

it’s an Enduro. Er, no, not with those street tires and vulnerable boom box hanging below the motor. Internet wags have unkindly suggested that the Versys resembles Alf, the furry alien from the defunct television sitcom, but what we’ve got here is an emerging new style, an amalgam of adventure-bike, standard and supermoto, with no dirt pretense whatsoever. Think mid-size Triumph Tiger, one of our favorite bikes of 2007.

Too bad the guys in the Plastics Department weren’t reined in when they suggested the “beauty” panels that cover the swingarmpivot area-that kind of

dime-store frippery just isn’t needed here. They should have spent more time with the instrument cowl, which delivered an annoying harmonic thrum between 3000 and 4000 rpm. Apparently the problem has been diagnosed and a retro-fix is forthcoming.

Minor criticisms, though, for a bike that always had me taking the long way home, or itching for any excuse to go riding. (“Need more milk, Hon? We’re down to our last gallon.”) The Versys has been well-received overseas and across the border, now it’s coming here. Good move, Kawasaki. Shall we all meet at, say, 75 mph? □

For more on the Kawasaki Versys visit www.cycleworld.com

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontTen Rest, 2007

August 2007 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsToo Much Bike, Not Enough Road

August 2007 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTales of the Testastretta

August 2007 By Kevin Cameron -

Hotshots

HotshotsHotshots

August 2007 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Tailpipe Chronicles

August 2007 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

RoundupCrocker Shocker

August 2007 By David Edwards