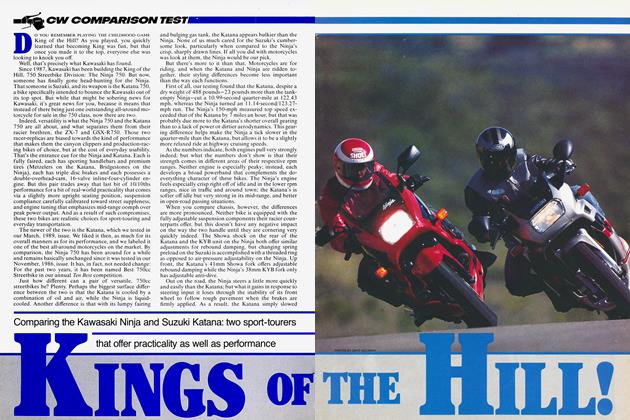

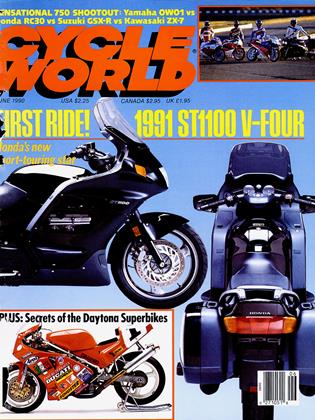

The Super 750s

CW COMPARISON TEST

HONDA RC30 vs KAWASAKI ZX-7 vs SUUKI GSX-R vs YAMAHA OWO1

WELCOME BACK, 750cc sportbikes! Only a couple of years ago, the 750 sportbike class almost vanished. Honda already had dropped the VFR750 from its model line and Yamaha was phasing out its FZR750, both wonderful machines that never quite caught on. Kawasaki retained its Ninja 750, and though it was a delightful all-around motorcycle, it was not the bike that fans of super-serious sportbikes lusted after. For them, only Suzuki's lightweight, race-inspired GSX-R filled the bill.

Last year, however, things began to turn around. Kawasaki introduced the all-new ZX-7 to battle head-tohead against the GSX-R750. And now, Honda and Yamaha have returned to the arena with wildly exotic—and outlandishly expensive— repli-racers sold in limited numbers only. Honda’s 3-year-old RC30 finally comes to America, priced at $14,998, and Yamaha’s $16,000 FZR750RR, otherwise known as the OWOl, was obtainable early in the year—if you had the right connections. The OWOl used in this comparison was borrowed from baseball great Reggie Jackson, who wanted one of the country's most-exclusive streetbikes.

In comparison to the asking prices of the RC and OW. the Suzuki’s and Kawasaki’s stickers, $6199 and $6449, respectively, seem almost tame. Though outwardly littlechanged from last year’s offerings, both bikes have been upgraded for 1990. The GSX-R750 returns with a substantially revised chassis and engine in an effort to keep it the darling of production-class roadracers. The ZX-7 also has a stronger engine and reworked chassis this year.

Because this is such a landmark year for 750cc sportbikes, we gathered the four machines for an extensive comparison test. Before the festivities got underway, though, we equipped each bike with Pirelli’s excellent MP7 Sport radial tires, so that we'd be comparing chassis and suspension differences, and not the dissimilarities in the bikes' stock rubber. Then, with the motorcycles on equal footing, we took them to the dragstrip, ran them past a radar gun. flogged them around Riverside Inter-

national Raceway and rode them for 1200 miles on the street.

In the end, we found the best bike of the class. But in the process, we also learned a few things about costeffectiveness and about the irresistible pull that ultra-exclusive, ultraexpensive motorcycles have over people. Most of all. we found that no matter how good sportbikes have been in the past, the 750s of 1990 just made the old standards of comparison obsolete.

That’s really not so surprising, as all four were derived from factory racebikes, and as such, the Honda RC30, the Kawasaki ZX-7, the Suzuki GSX-R750 and the Yamaha OWOl represent the most-intense efforts of the Japanese companies to produce state-of-the-art sportbikes. They are just bearable on straight roads, but on zigzagging sections of asphalt, they work in the way that God—and a few Japanese engineers— intended. And they prove that the real seeret to going fast is not just in having the most power, hut in how well you can control that power. The more control a bike allows, the faster you can ride it, no matter if you're on the track or on the street.

That's most evident on the Suzuki. The GSX-R has great street manners, with suspension that handles aggressive backroad riding with ease. It soaks up bumps effectively and still provides a firm enough ride to keep the bike from squirming around through higher-speed corners. Its light steering and willingness to change direction through corners make the Suzuki one of the easiest bikes to ride quickly in the twisties.

On the track, however, the Suzuki suffers from too-soft suspension that allows the bike to shake its head up front, and wallow in the rear. T hat the Suzuki has been such a dominant roadracer (with appropriate suspension tweaks) attests to the soundness of its basic chassis; but in street trim, it is simply not on par with the rest of the class. Consequently, during our racetrack portion of the test, the GSX-R was consistently 3 seconds a lap slower than the fastest bike.

Things are just the opposite with the Kawasaki, which delivers a harsh ride on the street. The fork's springing and damping rates are in the ballpark; but the back end suffers from an odd combination of a soft spring and a shock linkage that seems to increase the wheel rate too progressively as the rear suspension compresses. As a result, the ride is acceptable over small irregularities and ripples, but it turns brutal on bigger bumps and potholes. And the hard seat doesn't help matters, either. This makes for a punishing ride on all but glass-smooth roads. And that’s a shame, because the ZX-7 has the most-roomy riding position of this quartet.

Put the Kawasaki on a racetrack. though, and it becomes a different animal. Not only are racetracks generally smoother than the average road, but the significantly higher cornering loads they make possible are better suited to the abrupt progressiveness of the ZX-7’s rear suspension. In this environment, the Kawasaki doesn't seem overly harsh, and the firm suspension helps give it a secure feeling during extremely hard cornering. It does sometimes shake its head just a bit, but not as much as the Suzuki. It also takes more effort to pitch the ZX-7 into a turn than does the Suzuki, but the Kaw is more stable and predictable once it is fully heeled over.

So, too, is the Yamaha more suited for racetrack use, but for different reasons. Technically, the OWOl is not street-legal in the U.S. because, as delivered, it lacks turnsignals, mirrors and EPA certification. But it's a wonderful road machine anyway, which isn't surprising considering that in the rest of the civilized world, it is delivered in street-legal form. Its seating position is more comfortable than the Suzuki’s, even if it is just a bit more cramped than the Kawasaki's. The OWOl also requires more of a reach to the handlebars than the other bikes do, but at least the rear portion of the fuel tank is narrow, which makes hanging-off easy during hard cornering.

Not only that, the Yamaha comes with some of the best suspension components found on a production bike. Its Öhlins shock offers a myriad of adjustments, from ride height to remote spring-preload adjustments to compressionand rebound-damping adjustments. The Showa fork also has adjustments for preload, and for compressionand rebound-damping.

Once dialed-in, the Yamaha's suspension feels light-years beyond the Suzuki’s and Kawasaki’s. The fork makes bumps all but disappear, while the shock provides a near-perfect balance of low-speed suppleness and high-speed firmness. The suspension also contributes to the bike’s handling, which is dead-solid and wonderfully confidence-inspiring. To bank over into a turn, the OW requires a slightly firmer push on the bars than do the other three bikes, but it is unflappable once it is actually in the turn. The Yamaha rewards most when ridden hard and flicked quickly into the corners, but it works fine even with less-aggressive tactics.

Even though the Yamaha offers extraordinary cornering competence, the Honda is better yet. Indeed, it leads the pack in handling both in the twisties and on the track. It also is the smallest-feeling and the secondlightest of the four. And in terms of rider ergonomics, only the Kawasaki is slightly better. The RC30 has the shortest reach from seat to bars, and its seat pad is far more comfortable than it looks, due to its generous width and intelligent shape. The footpegs are located high above dragging limits, yet they don't cramp the rider's knees as badly as the Suzuki's.

But more than anything else, the chassis is what elevates the RC30 above the others. The bike has truly incredible suspension, suspension that makes you want to run over big. gnarly bumps on purpose just to see if you can feel them. As you might expect, the fork and shock have adjustable everything; and unless those adjustments are turned way out of whack, the RC30 seems able to cope admirably with everything the pavement can throw at it. from abrupt little bumps at low speeds to pavement moguls encountered at three-figure speeds. If there's any production motorcycle sold anywhere with better suspension, we've never ridden it.

As you might expect, then, the RC30 also has exemplary cornering manners. It has the most-neutral steering of the bunch, and only the Suzuki requires a lighter effort on the bars to initiate a turn. The Honda allows line changes in mid-turn without the slightest fuss, and it doesn’t exhibit much tendency to stand up while being braked when heeled over. On fast, smooth corners, it is, for all intents and purposes, flawless; and even when flogged around undulating corners at high speed, the Honda moves up and down on its suspension smoothly and in perfect unison at both ends, without even the slightest trace of wiggles or wobbles. This bike, more than any motorcycle in recent memory other than perhaps the Yamaha FZR400, can make a mere mortal feel like a world champ.

But while the Honda wins the handling and suspension wars handsdown, its engine is merely terrific. The V-Four's powerband begins just above idle and ends at the 12,500rpm redline, exhibiting three distinct personalities along the way. At low rpm, it rumbles along fairly innocently, although even tiny throttle openings seem to accelerate the bike with disarming ease. Just above 5000 rpm, that rumble turns to a no-nonsense, get-outta-my-way growl as the entire machine shudders with power pulsations that seem to grow more intense with every additional revolution. And above 10,000 rpm. the growl turns into a full-on Superhike howl that makes banging shifts at redline with the extra-close-ratio six speed gearbox one of the great aural thrills in motorcycling.

To no one’s surprise, the RC30 was the quickest around the track, a full second up on the second-place bike, and it ripped past our radar gun at 153 miles per hour—proof of mega-horsepower lurking beneath its fiberglass-reinforced plastic bodywork. Its slow quarter-mile time of 12.07 seconds can be attributed to the roadracing gearbox’s ultra-tall first gear, which is taller than second gear on most other bikes and made launching the RC a chore.

Riding the RC30 at high rpm does, however, show the bike's one great weakness: engine heat. The RC blasts the rider’s thighs and crotch with more heat than just about any other motorcycle on the market. If it doesn’t make you sterile, it at least will make you very uncomfortable.

The Suzuki's engine is a much more refined unit, even if it isn’t as powerful everywhere as the Honda’s. The air-and-oil-cooled inline-Four pushed the Suzuki up to 148 miles per hour, making it the slowest bike in the class-though it's ludicrous to call any 148-mile-per-hour motorcy cle "slow." But the GSX-R also went through the quarter-mile in 10.79 seconds, which is the fastest time we have ever measured for a 750. On the street, the Suzuki lacked the low-end power of the other bikes, having vir

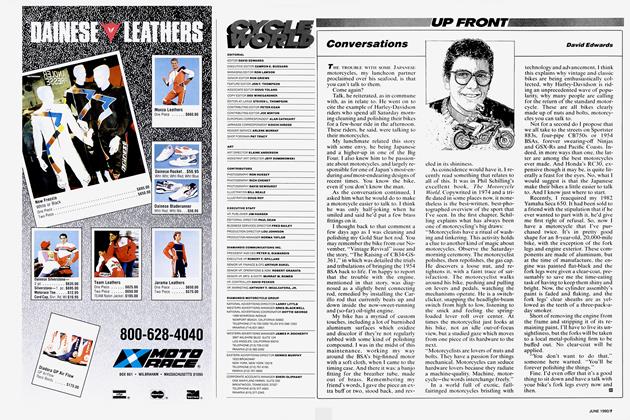

TECH LOOK: RC30

AS A CLASS, SPORTBIKES, HAVE been evolving more quickly than any other kind of mo torcycle on the road. Last year’s best often has to struggle to stay on top. So when Honda decided to bring the RC30 to America, we wondered if the three-year-old design would be competitive in the rapidly changing world of the 750cc sportbike.

Not that the RC30 lacks the credentials to climb to the top: It is a collection of some of the bestworking parts ever put on a motorcycle. It is powered by the third generation of Honda’s 748cc V-Four, a solidly mounted, liquid-cooled engine that uses gear-driven camshafts, and a 360-degree crankshaft like the original 1983 750 Interceptor. That crankshaft configuration gives the bike a droning exhaust note, one that sounds better as the revs climb toward the 12,500-rpm redline. The RC30’s engine also has titanium connecting rods topped with lightweight, two-ring pistons.

To get the bike to meet EPA standards, Honda had to make several small changes to the engine. First, Honda added air injection to the front two cylinders for cleaner emissions. And second, it installed slightly smaller exhaust-pipe collars to reduce exhaust noise. These changes have taken away a couple of horsepower, but the machine in European form puts out a claimed 1 12 horsepower, so the loss is not enough to be noticeable.

But it is the chassis which is most impressive. Five sided, aluminumbeam frame rails connect the steering head and swingarm pivots together, with the engine hanging beneath the rails. The formidable, single-sided swingarm allows the rear wheel to be easily removed without disturbing the rear disc or chain. The 43mm fork also features a quick-release system that allows you to take ofif the wheel without removing the brake calipers. The RC is the only one of the 750s in this test to come standard with a bias-ply tire on the front—the rest come with radiais. Another departure is the 18-inch rear wheel, as opposed to the 17-inchers which the other bikes use, although like the others, the RC’s rear is radial-shod.

Designers of the RC30 gave as much thought and time to the bike’s fit and finish as to its performance. The lightweight, fiberglass-reinforced plastic bodywork is beautifully finished. The hand levers, top

triple clamp and aluminum fuel tank are exquisite details that make you want to run hands over the machine. Our only complaint with the finish is that the paint chips easily.

There is one last item that helps make the RC30 so special. It is not an assembly-line bike in the pure sense. Instead, a small “team” is assigned to hand-assemble each bike. That is one of the reasons so few of the motorcycles can be built, why only 300 of them will make it to America this year and why it is so expensive.

But if ever there were a motorcycle worth $ 15,000, the RC30 is it.

$14,998

tually no get-up-and-go below 4500 rpm, though its slick-shifting gearbox made keeping the revs above 5000 an easy proposition. On the track, where it is no problem to keep the tach needle winging above 8000 or 9000 rpm, the engine performs better, though, as noted previously, the GSX-R was the slowest of the four at Riverside.

The ZX-7's engine performs im-

pressively on the track and the street. It pulls strongly from way down low, then kicks in hard around 4500 rpm. From there up to its 12,000-rpm redline, the ZX lunges forward and rockets off the corners as swiftly as any bike in the class. The only real problem with the engine is the clunky shifting of its transmission, especially in the lower gears.

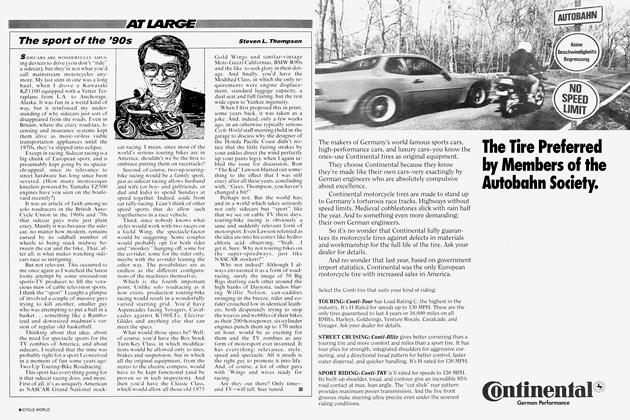

TECH LOOK: ZX-7

FIRST-YEAR EFFORTS ARE rarely flawless. So it was with Kawasaki's 1989 ZX-7. But the 1990 edition is on the road to perfection because the new ZX’s engine has been substantially updated, with a pumped-up powerband that is arguably the best in its class.

Essentially, the ZX-7’s liquidcooled, inline-Four powerplant has a whole new top-end. A new cylinder head features reshaped combustion chambers, with larger intake and exhaust ports, though the compression ratio remains 11.3:1 and the displacement stays at 748cc. The intake ports are still hand-polished, but the ports accommodate larger valves. Bigger, 38mm carburetors match up to larger intake tracts, and on the exhaust side, there’s now a 4-into-l pipe, which replaces last year’s 4into-2-into-l unit.

In addition, the pistons are lighter because they have been shortened 2mm from the top of their crowns to the middle of the piston pins, which also are lighter this year. More weight savings came from lightening the engine’s steel connecting rods.

Those changes have given the ZX7 a more-responsive engine that revs more quickly and pulls harder in the upper end of its powerband. That’s not surprising, because most of the ZX’s engine changes have come directly from last year’s factory racing kit. There has only been a l-horsepower gain, giving the bike a claimed 108 horsepower, but the ZX feels stronger throughout the powerband than did last year’s model.

Other mechanical alterations include fitting a curved radiator with greater coolant capacity, and a larger cooling fan. And the oiling system has gone through some changes, with a new oil-cooler and shallower oil pan that reduces the oil capacity from 3.9 quarts to 3.5.

While beefing up the engine, Kawasaki worked on the ZX’s chassis, as well. The most-noticeable change is the new swingarm. Gone is last year’s box-section component with its bridge-work upper-brace section, and in its place is a stamped-aluminum unit with recessed chain adjusters. Not so obvious are l-millimeterthicker aluminum frame sections, a hollow rear axle and lighter wheels. The ZX weighed-in on our scales 5 pounds lighter than last year’s bike.

Otherwise, the ZX-7 remains the same. The six-speed transmission keeps the same ratios, and the brakes and the suspension components, which consist of a 43mm cartridge fork up front and multi-adjustable, non-reservoir single shock at the rear, have not been changed from 1989.

As our testing showed, next year Kawasaki would do well to concentrate on suspension refinements. That it went 5 miles per hour faster and rushed through the quarter-mile three-tenths of a second quicker than last year’s ZX-7 shows that Kawasaki already has done it right when it comes to engine modifications.

$6449

Nonetheless, the ZX's tremendous mid-range power makes the bike easy to ride aggressively on the street, as well as on the track, where it set the second-fastest time, nudging out the Yamaha by three-tenths of a second.

In the quarter-mile, the ZX posted a 10.95-second time, and it blasted to a 152-mile-per-hour top speed. That quarter-mile time was the second fastest of the quartet. but its top speed was down 8 miles per hour to the speed king, the OWO1. The Ya maha barreled to an impressive 160 miles an hour-just three miles per hour slower than our test 1989 FZR 1000—making it the fastest 750 we've ever tested, with a number that few production motorcycles of any size can better.

Like the Honda, the OW has a tall first gear (but still not as tall as the RC30's) that prevented it from posting better quarter-mile times, though 11.20 seconds is nothing to be ashamed of. But above all, it is the civility of the Yamaha's engine that is so impressive. Its low-end output is stronger than the Suzuki's but not on par with the Honda's or Kawasaki's, while its top-end punch-which be gins at around 9000 rpm and contin ues to the 13-grand redline-is argu ably the best of the lot. But the flow of power is so silky smooth, and the transition into the powerband so

TECH LOOK: GSX-R

IN THIS AGE OF $16,000 SPORTbikes, it would be easy to over look Suzuki's GSX-R750, the lowest-priced 750 repli-racer. But if you take the time to study the GSXR, you quickly come to the conclusion that it’s a miracle this bike doesn't cost that much.

The 749cc engine, first introduced in 1985, is air-and-oil cooled. Finepitch cooling fins allow heat to dissipate from the cylinders while oil is injected to the tops of the combustion chambers, and blasted up to the bottoms of the piston crowns. To help with the cooling duties, Suzuki added a curved oil cooler for 1990. It is larger than the previous units, so to get the taller oil-cooler to fit, the steering head was kicked out a small amount, and the bend in the side frame rails was altered. These changes have resulted in a stronger steering head with a less-steep angle—25.5 degrees as opposed to 25.0. Those alterations and a slightly longer swingarm contribute to the half-inch-longer wheelbase.

Other changes to the chassis have been to add strength. The swingarmwall thickness has been increased from 4.3 to 5mm. and the mounting bosses for the rear shock have been beefed up. In addition, Suzuki installed a 5.5-inch-wide rear wheel, and upgraded the shock to an aluminum-body, remote-reservoir unit that has compressionand rebounddamping adjustments, in addition to spring-preload adjustments.

The engine also has been revised for the new season. When the GSXR was extensively redone for 1988, it received larger bores and shorter strokes. But race tuners weren't happy with the performance of that engine, because they were unable to squeeze enough mid-range power from it. So they often resorted to using the cylinders from the older, pre1988 GSX-R engines. For 1990, Suzuki has gone back to those earlier bore-and-stroke dimensions of 70 x 48.7mm in an effort to get more midrange performance out of the engine, though in comparison to the other three bikes tested here, the GSX-R still comes up lacking in that department.

Along with the changes in the bore and stroke, Suzuki also reworked the combustion chambers to be more dome-shaped, and decreased the valve sizes while installing a milder exhaust cam. Furthermore, the bike breathes through new, 38mm carburetors, as opposed to the 36s used on last year’s model. It also uses a new, 4-into-l, stainless-steel exhaust pipe, which gives the GSX-R more cornering clearance than it had with last year’s 4-into-2 pipes.

Granted, most of the changes Suzuki made could be considered relatively minor. But taken collectively, they add up to a significantly revised motorcycle, one that absolutely smokes ahead of other 750s in straight-line acceleration. And the level of sophistication and degree of fit and finish on the machine make it look like a steal for its price.

$6199

gradual, that there are no discernible blips or dips anywhere in the rpm range. The exhaust powervalve system (EXUP) plays a large part in this smoothness by boosting the low-end and mid-range power.

But the OWOl simply doesn’t generate gobs of low-end power; and that, combined with the tall first gear, explains why it posted only the

third-fastest time around Riverside, where several extremely slow and bumpy first-gear turns handicapped the bike’s lap times.

What became clear the longer we spent time with this group of motorcycles is that there is no loser here. These are four of the fastest, quickest, best-handling motorcycles ever made, and not one of them could be construed as an inferior motorcycle.

TECH LOOK: OWO1

WHEN YAMAHA DROPPED ITS FZR 75OR from its Ameri can lineup at the end of 1988, it had no immediate replacement. After all, that FZR had all the trick parts, and according to the spec sheet, it should have been a winner. But it didn’t perform as well on the track as it could have, nor did it sell as well as it should have. But then, it was expensive for its day, listing for $6899. Now, Yamaha has replaced the FZR750 with the OWO 1, and has

taken care of the performance shortcomings by building a truly leadingedge sportbike, one that bristles with exotic metals and racetrack-oriented features.

However, the OWOl does not have all that much in common with previous Yamaha 750s, other than both machines derived from the YZF750 factory racebike designed to win the prestigious Suzuka 8-Hour endurance race. In fact, the OWOl’s liquid-cooled, inline-Four has more in common with the current Yamaha FZR 1000. The cylinders, like those on the 1000, are angled forward at 40 degrees, as opposed the old 750’s 45 degrees. The cylinders have been rotated on the cases, and this allows the front axle to be moved closer to the

centerline of the 749cc engine. This new engine is almost 1 inch shorter top to bottom than the previous 750 motor, in part because of a 5.6mmshorter stroke. It is also shorter from front to back than the older engine, which accounts for the OW having a wheelbase of only 56.8 inches.

Internally, the OWOl uses titanium connecting rods. The reason for this is that titanium rods are stronger and lighter than steel rods, theoretically upping reliability while lowering the amount of reciprocating mass. Also, World Superbike rules specify that racebikes must use stock rods, or rods made from the same materials as stock, hence the titanium rods on the OWOl (and the RC30). Last season, some OWO Is were having what many thought were rod problems, but the company diagnosed that piston pins were seizing. For 1990, the rods have been beefed up at the top, and there is more pin clearance. Two-ring pistons are used for reduced friction loss.

One other interesting feature on the engine is the liquid-cooled oil filter. The engine uses a spin-on, cartridge-type filter that mounts on top of a cooler. Also, the engine has been developed all along to employ the EXUP exhaust system, which contributes to lowand mid-range power, but also allows the engine to breathe freely at high engine speeds.

Other than using large aluminum beams, there are few other similarities between the OWOl’s and the FZR’s chassis, and in fact, there are no interchangeable parts. Suspension for the OWOl is essentially raceready, with a Showa 43mm, cartridge fork and Öhlins shock.

Overall, the Yamaha has enough trick bits and pieces—like its aluminum fuel tank with hand-welded quick-fill adapter—to justify its premium price, though with its performance it would be worth it even if it were made out of mud. About the only disappointment we find with the OWOl is that there are so few of them to go around.

$16,000

Still, we found the RC30 to be the best bike in the class. It does everything you could ask for and does it so well that you begin to think that $ 15,000 is a reasonable asking price. But Honda only imported 300 RC30s into America, and that, plus its high price, lends it an otherworldly quality. If you can find one— and can afford it—you will have one of the best sportbikes ever built.

Sadly, the Yamaha comes in even more limited numbers. There are only 21 OWOls in America, and only one of those—our test bike—is destined to see street duty; the rest have been sold to racers. It is not street-legal, though turnsignals and mirrors would cure that. As this year’s Daytona 200 results show, there is no doubt the Yamaha makes a terrific racebike, but it is not $10,000 better than the GSX-R and ZX-7. It is $10,000 more exclusive, however, and to some people, it’s worth that much to have something no one else can get.

That leaves the Suzuki and the Kawasaki, readily available motorcycles you can buy at a reasonable price. In fact, for the price of one RC30 or OWO1, you could buy both the GSXR and the ZX-7. Which is the best of these affordable two can be determined by what you intend to do with it. If you are looking for a 750 sportbike exclusively for the street, the GSX-R would be a good choice. Its suspension is more comfortable than the ZX-7’s, even if its ergonomics aren’t. The Suzuki has a more-integrated, more-refined feel than the Kawasaki, and it’s $250 less expensive.

But if you plan a bit of racing, or just want a harder-edged sportbike for Sunday-morning rides, the Kawasaki ZX-7 is right up your alley. It is a shock linkage and seat away from being the unequivocal best in class. It has a tremendous engine and a good riding position for a bike of this type.

In the end, then, we’ve got two winners here. For those of you with deep pockets, don’t settle for anything less than the Honda RC30. For the rest of us who have to juggle mortgage installments, car payments and braces for the kids, take the ZX-7 and run.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontConversations

June 1990 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeThe Sport of the '90s

June 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsLegal Tender

June 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupBrm Spyder Upgrading the Gsx-R1 100's Flash Factor

June 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupBmw K75rt Making A Virtue of Adequacy

June 1990 By Jon F. Thompson