KAWASAKI KDX200 VS. YAMAHA WR200

CW COMPARISON TEST

Battle of the woods rockets

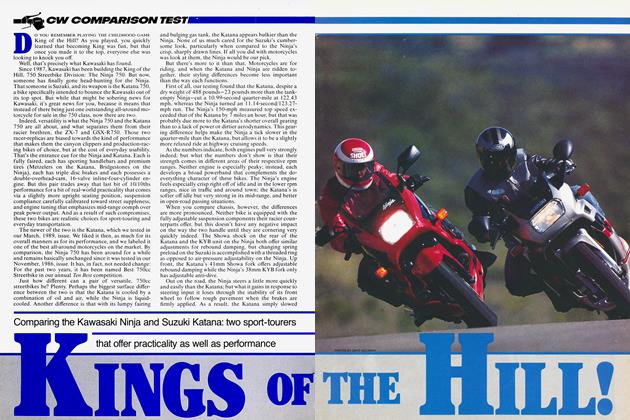

THE BEST-KEPT SECRET IN OFF-road riding has just been blown. For the past six years, Kawasaki, with its KDX200, has been the only company to recognize that a good, 200cc, two-stroke enduro bike can mow through a tight woods section quicker than a runaway chain saw. In 1984, Yamaha had a contender with its excellent IT200, but that model was dropped, and the class was left to the KDX. Well, Yamaha is back, this time with the WR200.

Yamaha spokesmen are quick to admit that the Kawasaki 200 was the target when designing the WR, though circumstances beyond their control may have deflected their aim a bit. The genesis for the bike goes something like this: Yamaha's U.S. R&D department took a YZ125 motocross chassis and bolted in the powerplant from a DT200R, a Japanesemarket dual-purpose bike. The home office liked the result so much that it decided to make the bike a replacement for the aging domestic-market DT200R. But that meant the YZ chassis had to be beefed up to handle the stress of street riding. And it meant the engine’s counterbalancer—which the U.S. team wanted removed to add low-end punch — would remain intact. So, what began as a dirtbike was modified into a dual-purpose bike for the Japanese and then de-streetified for the U.S. market. Given this rather convoluted approach, how does the WR stack up against the purpose-built KDX?

Weighing the two bikes furnished the first clue. The KDX200, at 233 pounds without fuel, is no featherweight. But it’s considerably lighter than the WR200, which hits the scales at a porky 247 pounds. If that doesn’t sound heavy to you, consider that Yamaha’s WR250 weighs just 228 pounds, 19 less than its smaller sibling. Granted, the 250 lacks the 200’s lights, sidestand and EPA-legal silencer, but it is clear that the WR200 would have benefited from a stricter diet program. Even the bigbruiser WR500 weighs in at just 1 1 pounds more.

The WR feels larger than the KDX, too, thanks to its 1.5-inchtal 1er seat height and wider front section. And the Yamaha retains its big feel on the trail: Its steering is slower than that of the KDX, and its elevated seat height makes dabbing difficult for all but tall riders. In contrast, the KDX200 actually feels lighter and smaller than it is, its weight masked by quick steering geometry.

Both bikes boast solid, flex-free chassis, and both go where they are pointed, stay on the trail well and don’t get overly busy at high speeds, with the WR having a slight edge in high-speed stability. The Yamaha requires more rider input than does the Kawasaki when changing directions or negotiating tight turns, but the WR's slower, more neutral handling may be preferred by some riders.

Judging the suspension of these bikes based solely on a visual basis gives the advantage to the Yamaha, courtesy of its inverted fork. But a few miles of rocky, rutted, tree-rootinfested trail shows that the KDX’s conventional-style fork —the benefactor of several years of fine-tuning-is smooth throughout its travel, rarely bottoms and absorbs impacts well, with little front-wheel deflection noticed. The rear suspension is a good match to the fork and supplies the same high degree of control and rider comfort.

Things aren't quite so happy with the Yamaha. The inverted fork swallows slow-speed bumps well, but it exhibits midrange harshness. Rearsuspension action is even more severe. A constant midrange jolt punishes the rider.

Kawasaki’s constant refinement of the KDX200 is most apparent in its engine. Smooth-running, responsive and powerful, with a reed-valve intake and a mechanical exhaust valve, the engine has a wide, highly usable powerband that’s accentuated by a strong midrange pull. That comes in handy when climbing steep hills and blasting through deep sand.

On paper, the Yamaha WR200’s engine, with its counterbalancer, case-reed intake and electronically controlled exhaust valve, should be at least as powerful as that of the KDX. Our first ride on a WR proved disappointing: It had no low-end, a meek midrange and absolutely zero top-end power. Hills that the KDX easily climbed in second gear were impossible obstacles on the WR200.

The WR was returned to Yamaha for a check-up, and was diagnosed as having a faulty exhaust-control valve cut-out and cylinder exhaust port shape. After replacement of the cylinder, exhaust-control mechanism and piston, the WR ran well, with power equal to that of the KDX200. Even though its dirtbikes are sold without warranties, Yamaha told us that manufacturing defects such as our WR200 had are covered for 90 days after purchase.

Engine problems cured, we continued testing. Most riders liked the WR200’s handlebar, footpeg and seat relationship, especially those over 6 feet tall, who felt a little cramped on the KDX. And, like the Kawasaki, the Yamaha’s standard equipment includes strong disc brakes, an O-ring drive chain, a kickstand, handguards, a large fuel tank, an odometer, lights and an EPA-legal silencer.

What the WR200 doesn't have is a price advantage over its green rival. In fact, it costs $600 more than the KDX. That price disparity would be hard to justify if these two bikes were equally competitive, which they aren’t. Lighter and with better suspension, the KDX200 is still king in the woods. One-upping Kawasaki is going to take a stronger, more focused effort than Yamaha has shown with the WR200. ra

Kawasaki KDX200

$2899.

Yamaha WR200

$3499

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1991 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

October 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

October 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1991 -

Roundup

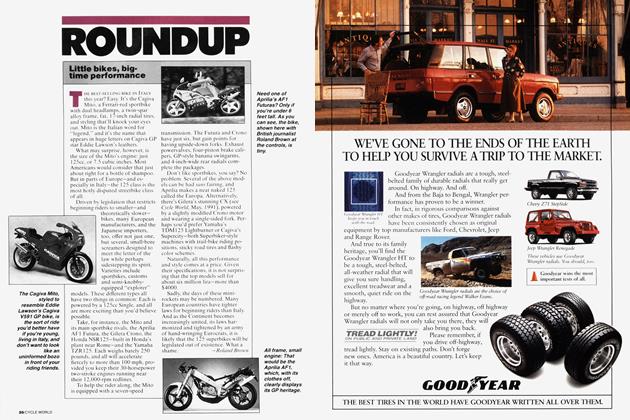

RoundupLittle Bikes, Big-Time Performance

October 1991 By Roland Brown -

Roundup

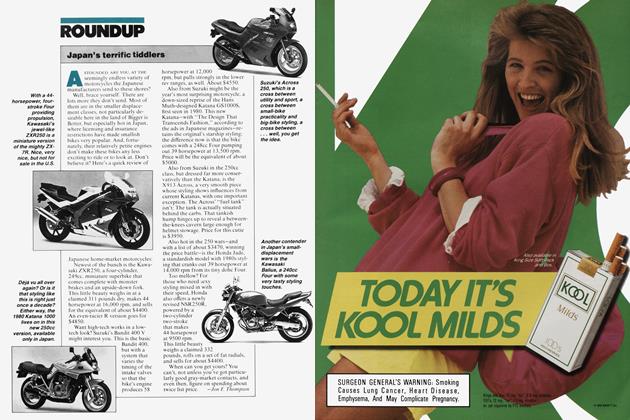

RoundupJapan's Terrific Tiddlers

October 1991 By Jon F. Thompson