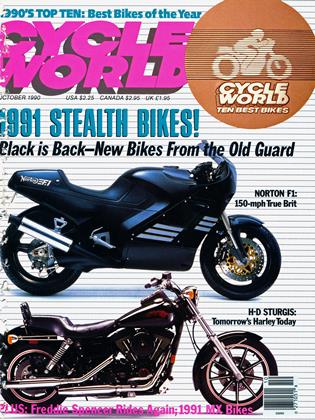

IN PURSUIT OF THE PERFECT SPORTBIKE

PERSONAL PROJECT

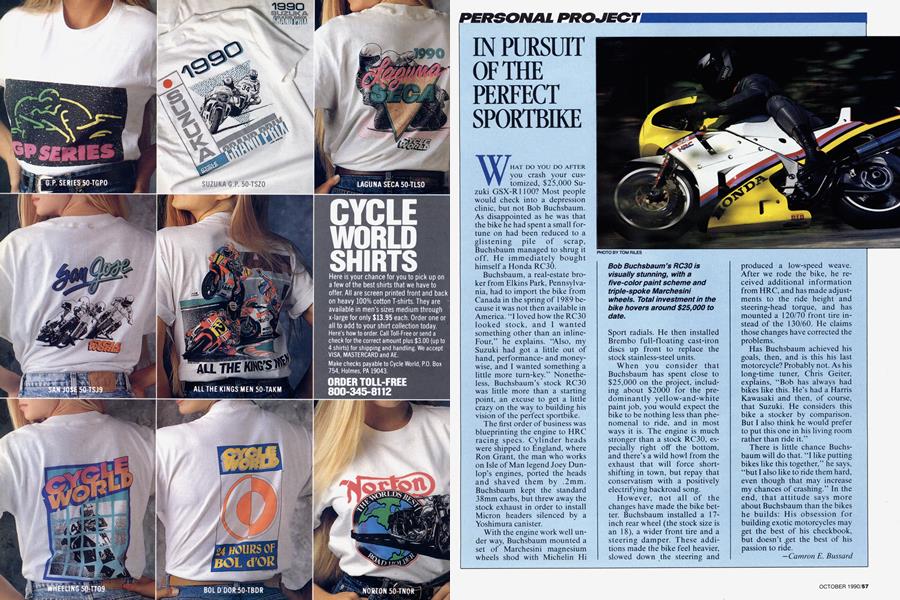

WHAT DO YOU DO AFTER you crash your customized, $25,000 Suzuki GSX-R1100? Most people would check into a depression clinic, but not Bob Buchsbaum. As disappointed as he was that the bike he had spent a small fortune on had been reduced to a glistening pile of scrap, Buchsbaum managed to shrug it off. He immediately bought himself a Honda RC30.

Buchsbaum, a real-estate broker from Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, had to import the bike from Canada in the spring of 1989 because it was not then available in America. “I loved how the RC30 looked stock, and I wanted something other than an inlineFour,” he explains. “Also, my Suzuki had got a little out of hand, performanceand moneywise, and I wanted something a little more turn-key.” Nonetheless, Buchsbaum’s stock RC30 was little more than a starting point, an excuse to get a little crazy on the way to building his vision of the perfect sportbike.

The first order of business was blueprinting the engine to HRC racing specs. Cylinder heads were shipped to England, where Ron Grant, the man who works on Isle of Man legend Joey Dunlop’s engines, ported the heads and shaved them by .2mm. Buchsbaum kept the standard 38mm carbs, but threw away the stock exhaust in order to install Micron headers silenced by a Yoshimura canister.

With the engine work well under way, Buchsbaum mounted a set of Marchesini magnesium wheels shod with Michelin Hi Sport radiais. He then installed Brembo full-floating cast-iron discs up front to replace the stock stainless-steel units.

When you consider that Buchsbaum has spent close to $25,000 on the project, including about $2000 for the predominantly yellow-and-white paint job, you would expect the bike to be nothing less than phenomenal to ride, and in most ways it is. The engine is much stronger than a stock RC30, especially right off the bottom, and there’s a wild howl from the exhaust that will force shortshifting in town, but repay that conservatism with a positively electrifying backroad song.

However, not all of the changes have made the bike better. Buchsbaum installed a 17inch rear wheel (the stock size is an 18), a wider front tire and a steering damper. These additions made the bike feel heavier, slowed down the steering and produced a low-speed weave. After we rode the bike, he received additional information from HRC, and has made adjustments to the ride height and steering-head torque, and has mounted a 120/70 front tire instead of the 130/60. He claims those changes have corrected the problems.

Has Buchsbaum achieved his goals, then, and is this his last motorcycle? Probably not. As his long-time tuner, Chris Geiter, explains, “Bob has always had bikes like this. He’s had a Harris Kawasaki and then, of course, that Suzuki. He considers this bike a stocker by comparison. But I also think he would prefer to put this one in his living room rather than ride it.”

There is little chance Buchsbaum will do that. “I like putting bikes like this together,” he says, “but I also like to ride them hard, even though that may increase my chances of crashing.” In the end, that attitude says more about Buchsbaum than the bikes he builds: His obsession for building exotic motorcycles may get the best of his checkbook, but doesn’t .get the best of his passion to ride.

—Camron E. Bussard

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

October 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

October 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1990 -

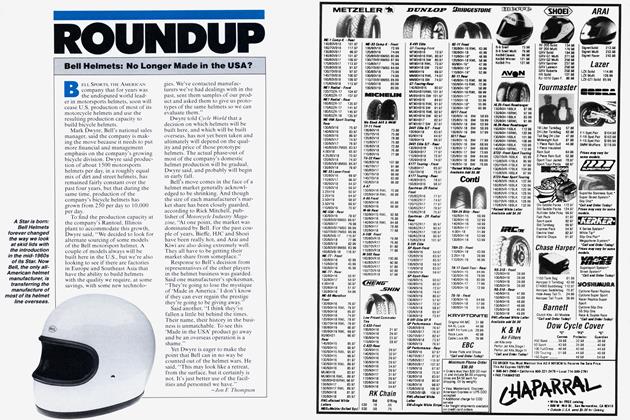

Roundup

RoundupBell Helmets: No Longer Made In the Usa?

October 1990 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Update: News From Cagiva, Aprilia And Ferrari

October 1990 By Alan Cathcart