STANDOUT SUZUKI

PERSONAL PROJECT

FORMULA FOR ATTENTION

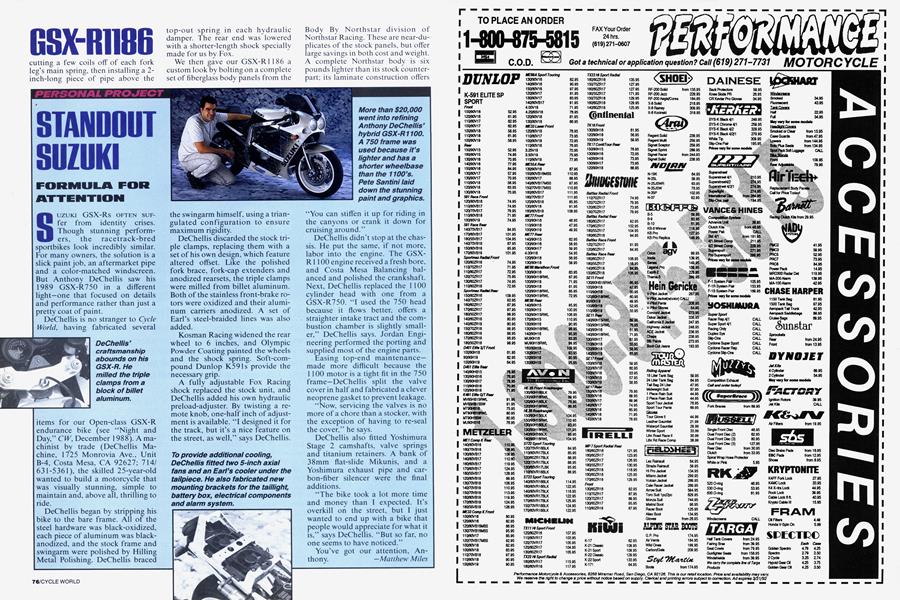

SUZUKI GSX-Rs OFTEN SUFfer from identity crises. Though stunning performers, the racetrack-bred sportbikes look incredibly similar. For many owners, the solution is a slick paint job an aftermarket pipe and a color-matched windscreen. But Anthony DeChellis saw his 1989 GSX-R750 in a different light-one that focused on details and performance rather than just a pretty coat of paint.

DeChellis is no stranger to Cycle World, having fabricated several

items for our Open-class GSX-R endurance bike (see “Night and Day,” CW, December 1988). A machinist by trade (DeChellis Machine, 1725 Monrovia Ave., Unit B-4, Costa Mesa, CA 92627; 714/ 631-5361), the skilled 25-year-old wanted to build a motorcycle that was visually stunning, simple to maintain and, above all, thrilling to ride.

DeChellis began by stripping his bike to the bare frame. All of the steel hardware was black-oxidized, each piece of aluminum was blackanodized, and the stock frame and swingarm were polished by Hilling Metal Polishing. DeChellis braced the swingarm himself, using a triangulated configuration to ensure maximum rigidity.

DeChellis discarded the stock triple clamps, replacing them with a set of his own design, which feature altered offset. Like the polished fork brace, fork-cap extenders and anodized rearsets, the triple clamps were milled from billet aluminum. Both of the stainless front-brake rotors were oxidized and their aluminum carriers anodized. A set of Earl’s steel-braided lines was also added.

Kosman Racing widened the rear wheel to 6 inches, and Olympic Powder Coating painted the wheels and the shock spring. Soft-compound Dunlop K59ls provide the necessary grip.

A fully adjustable Fox Racing shock replaced the stock unit, and DeChellis added his own hydraulic preload-adjuster. By twisting a remote knob, one-half inch of adjustment is available. “I designed it for the track, but it’s a nice feature on the street, as well,” says DeChellis.

paint graphics. “You can stiffen it up for riding in the canyons or crank it down for cruising around.”

DeChellis didn’t stop at the chassis. He put the same, if not more, labor into the engine. The GSXR1100 engine received a fresh bore, and Costa Mesa Balancing balanced and polished the crankshaft. Next, DeChellis replaced the 1100 cylinder head with one from a GSX-R750. “I used the 750 head because it flows better, offers a straighter intake tract and the combustion chamber is slightly smaller,” DeChellis says. Jordan Engineering performed the porting and supplied most of the engine parts.

Easing top-end maintenancemade more difficult because the 1100 motor is a tight fit in the 750 frame—DeChellis split the valve cover in half and fabricated a clever neoprene gasket to prevent leakage.

“Now, servicing the valves is no more of a chore than a stocker, with the exception of having to re-seal the cover,” he says.

DeChellis also fitted Yoshimura Stage 2 camshafts, valve springs and titanium retainers. A bank of 38mm flat-slide Mikunis, and a Yoshimura exhaust pipe and carbon-fiber silencer were the final additions.

“The bike took a lot more time and money than I expected. It’s overkill on the street, but I just wanted to end up with a bike that people would appreciate for what it is,” says DeChellis. “But so far, no one seems to have noticed.”

You’ve got our attention, Anthony. —Matthew Miles

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

March 1992 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

March 1992 By Peter Egan -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

March 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1992 -

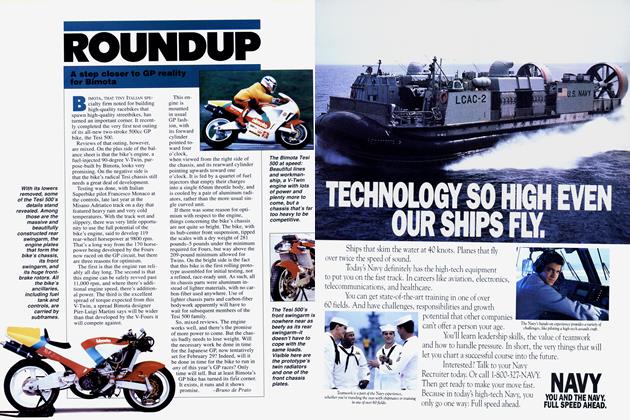

Roundup

RoundupA Step Closer To Gp Reality For Bimota

March 1992 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupAmerica 1: Gold-Plated Superbike

March 1992 By Jon F. Thompson