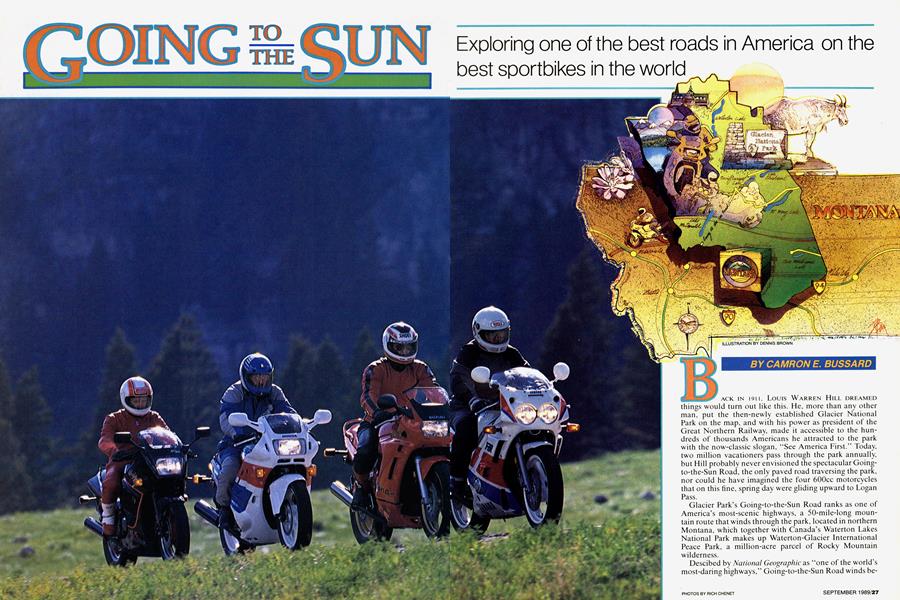

GOING TO THE SUN

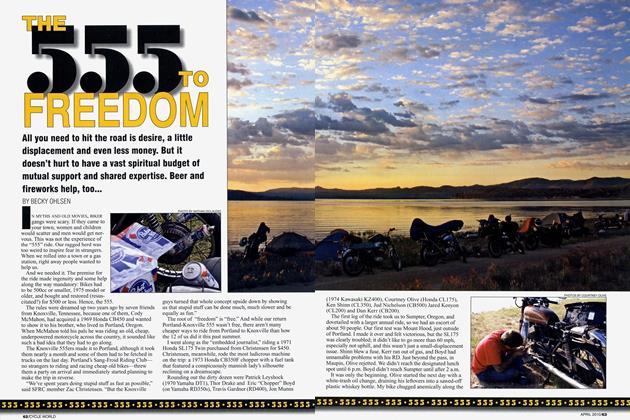

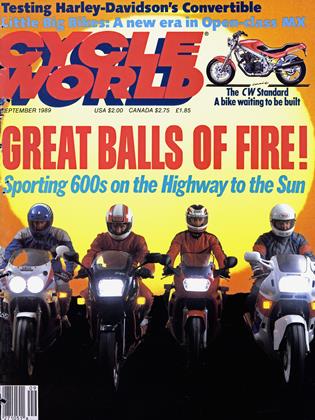

Exploring one of the best roads in America on the best sportbikes in the world

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

ACK IN 1911, Louis WARREN HILL DREAMED things would turn out like this. He, more than any other man, put the then-newly established Glacier National Park on the map, and with his power as president of the Great Northern Railway, made it accessible to the hundreds of thousands Americans he attracted to the park with the now-classic slogan, “See America First.” Today, two million vacationers pass through the park annually, but Hill probably never envisioned the spectacular Going-to-the-Sun Road, the only paved road traversing the park, nor could he have imagined the four 600cc motorcycles that on this fine, spring day were gliding upward to Logan Pass.

-Glacier Park's Going-to-the-Sun Road ranks as one of America’s most-scenic highways, a 50-mile-long mountain route that winds through the park, located in northern Montana, which together with Canada’s Waterton Lakes National Park makes up Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park, a million-acre parcel of Rocky Mountain wilderness.

Descibed by National Geographic as “one of the world’s most-daring highways,” Going-to-the-Sun Road winds beneath the remnants of the 20,000-year-old ice flows that shaped this region and fed its numerous lakes. The road is a paradise for motorcyclists, offering tight twists and turns, broad sweeping corners and countless breathtaking vistas as it snakes over the Continental Divide. A 45-milean-hour speed limit is enforced along the route, which shouldn’t be a problem, even for inveterate velocity mongers. After all, zapping through a place as brimming with beauty as Glacier National Park would be like speed-reading Tolstoy’s Anna Karenin or fast-forwarding a VCR through Gone With the Wind: It just isn’t done.

FOR OUR EXPLORATION OF THE ROAD, WE BOOKED cabins at Lake McDonald Lodge overlooking a body of water so clear and blue it looks like a trick done with mirrors, and spent a couple of days riding out of there. Even though bulldozer crews begin clearing the road in late April of snowdrifts that can scale up to 80 feet high, Going-to-the-Sun doesn’t open until the first part of June. We were there the day the highway opened and found crews still mopping up snow on some of the road’s higher sections.

One of the reasons to begin a Glacier Park trip at Lake McDonald Lodge is that besides offering reasonable accommodations, there are historical connections. Back in 1911, that’s where the first superintendent of the park, William Logan, began the initial construction on the Trans-mountain Highway—the name was later changed to the Going-to-the-Sun Road. According to records, he promised Congress that he would build a road “from the east to the west’’ of Glacier Park. However, Logan would die one year later and it would take 21 years for other men to finish the project he conceived.

Work on the road would have to wait until a few years after World War I, and continuous work didn’t begin until 1921, when Congress appropriated $100,000 for the project. Then, the problem was no longer money, but terrain. The route that now climbs so serenely toward the Garden Wall, a towering, saw-toothed section of granite that marks the Continental Divide, proved treacherous and demanding for workers, who had to hike several miles in, and several thousand feet up, to their work sites. Dynamite, pickaxes and shovels were the principle means of excavation, and once progress was made through what is now called the Loop—a sharp switchback that marks the beginning of the dramatic climb to Logan Pass—the work became even more difficult.

Besides the sheer difficulty of its construction, one of the things that makes the road so special is that from the very beginning it was designed for sightseeing by automobile. By the mid-Twenties, America was infatuated with cars, and the Going-to-the-Sun Road reflects that, with large scenic turnouts and only a mile or two of guardrail. Two-foot-high stone walls line the more-dangerous curves and some straight stretches of the road bordered by sharp drop-offs, but otherwise, there are few man-made objects to mar the view.

After the Loop, the roadway narrows and begins to ascend, providing vistas of craggy, snow-topped peaks and huge, U-shaped valleys carved by ice-age glaciers. Runoff from waterfalls fed by melting snow keeps this part of the road constantly wet throughout the summer, so it's recommended that riders stop and peer over edges of cliffs from the many roadside turnouts rather than do much gawking from the saddle. At a quarter-mile section named the Weeping Wall for the sheets of water falling onto the road from 75-foot cliffs, cloud-white mountain goats graze on narrow paths and, in late summer, grizzly bears feed in the forest just above the road. Altogether, 60 kinds of mammals, 250 kinds of birds and 1000 varieties of plants can be spotted in the park.

The final leg on the western slope up to 6680-foot-high Logan Pass is only a few of miles, but the trip can easily take hours because every pullout invites a sightseeing stop: The area’s sublime beauty is that seductive. At this altitude, the air is crisp, even in late spring, and snowdrifts that could completely cover small towns shoulder up against the road. A visitors’ center on the top of Logan Pass is a gathering spot for everyone on the road, and the many motorcyclists enjoying the ride on everything from Gold Wings to Moto Guzzis tend to congregate in the center’s parking lot.

It’s from Logan Pass that travelers get their first glimpse of Going-to-the-Sun Mountain, a spectacular, sheer-granite face that glows gold and bronze in the late-afternoon sun. There are many versions of how the mountain came to be named, but the most-interesting and poetic is an Indian legend which claims that Napi, the Old Man, came down from the Sun to help the Blackfeet tribe, and when he was done, went home, up the slope of the mountain.

As the road heads eastward and down from the pass toward St. Mary Lake, it changes entirely, becoming less spectacular but dryer and better suited for motorcycling. Part of the reason for the dramatic change is that work on the eastern section of Going-to-the-Sun didn’t begin until 1931, 10 years after the work began on the west section. Better construction techniques and easier terrain allowed this section to be completed in under two years. Then, too, the mountains take on a different look. They are pushed further apart than on the west, as sharp cliffs give way to broad valleys and high, grassy plains dotted with lakes. In the background is Triple Divide Peak, called “the crown of the continent,” because from there, water flows to three bodies of water—the Pacific Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico and, via Hudson Bay, the Atlantic Ocean.

T THE EASTERN END OF THE ROAD, ICE-GREEN St. Mary lake provides a visual counterpoint to Lake McDonald on the western tip of the route. The road drops to the lake from the sky, skirting steep walls several hundred feet above the water. Toward the top of the lake, the road hugs the shoreline before meandering into the village of St. Mary, which signals the conclusion of the Going-tothe-Sun Road, but not the end of the region’s natural beauty.

That's because Glacier National Park does not exist in a void, and the area surrounding the park is just as wild and beautiful as the park itself. In fact, the Highway 89, from St. Mary to the turnoff for the town of East Glacier, may well be the best motorcycling road in the entire area. It gets less travel than some of the other roads, and is in better condition, with smooth, sweeping curves arcing up and over small mountain ridges. Likewise Highway 2, which follows the southern boundary of the park back to the entrance at West Glacier.

Still, these two roads don’t compare with Going-to-theSun,and it’s unlikely that any ever will. At the road’s opening ceremony on July 1 5, 1933, Horace Albright, director of the National Park Service, said, “Going-to-the-Sun Highway fills the need for quick access to high country to see the glory of Glacier’s peaks and crags, but parallel roads would add little to the hurrying motorist’s enjoyment of the park. Let there be no competition of other roads with the Going-to-the-Sun Highway. It should stand supreme and alone.” By all accounts, it does.

But there are some potential problems for the highway. It is over 50 years old, and the natural forces which have carved the mountains themselves have been at work on the pavement that clings so precariously above the park’s ancient valleys, making substantial repairs inevitable. The process of maintaining and restoring the road is a difficult one, demanding a sensitivity to the historical significance of the road and a concern for the safety of its users. Nor is refurbishment inexpensive, and approval to begin any major renovation will likely take another five years.

But that’s all right. Nothing should be rushed when it comes to this spectacular section of highway. It is more than a road, and it is more than a scenic route. It is an engineering marvel and a monument to the American people, one that says we can do anything if we want it badly enough.

That’s the spirit that called 210,000 people a year to make the journey over Going-to-the-Sun Road even during the money-scarce years of the Great Depression. And you catch a sense of that spirit today when you travel the road and roll through its only two tunnels, painstakingly pickaxed out of the mountains, or when you stop, reach down and feel the stones that support the roadway and realize that they were shaped and positioned by hand half a century ago.

THE SENSE OF AWE, BOTH AT THE SCENERY AND AT the engineering triumph of the highway, is so strong on the Going-to-the-Sun Road that we found it hard to concentrate on suspension compliance or engine vibration or brake feel of our four test bikes. It was enough just to be on motorcycles, moving through the fresh, clean air and matchless landscape of Glacier National Park. The famous Western artist Charles Russell, who kept a log cabin by the shores of Lake McDonald until his death in 1926, is reputed to have once said, “In spite of gasoline, the biggest part of the Rocky Mountains belongs to God.’’ That’s still true today, of course, but on 50 miles of asphalt in a small corner of the Rockies, a few gallons of fossil fuel is all that’s required for automobile drivers and motorcycle riders to become willing, lifelong captives of a road going to the Sun.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

September 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

September 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

September 1989 By Peter Egan -

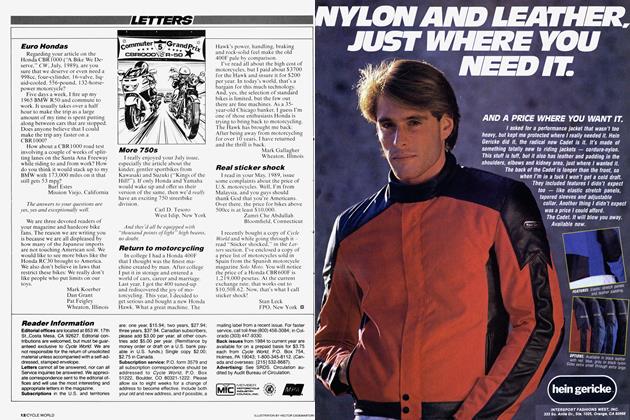

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupA New Supertwin?

September 1989 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Traffic Solution

September 1989 By Alan Cathcart