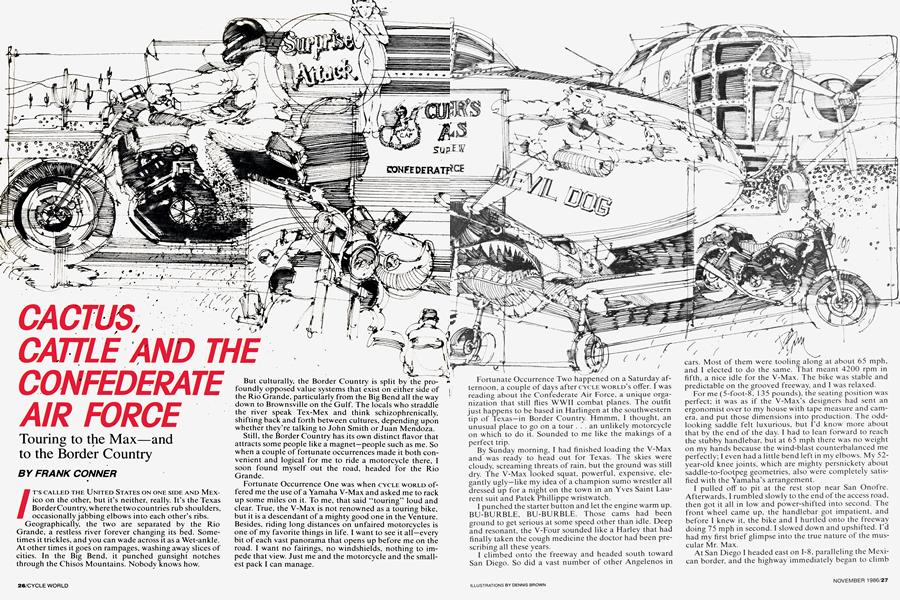

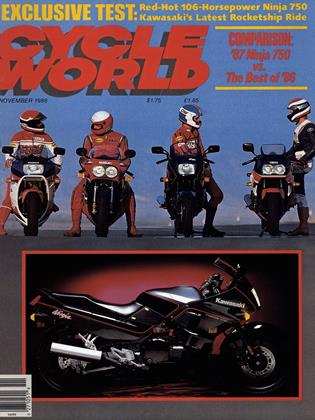

CACTUS, CATTLE AND THE CONFEDERATE AIR FORCE

Touring to the Max—and to the Border Country

FRANK CONNER

IT'S CALLED THE UNITED STATES ON ONE SIDE AND MEXico on the other, but it's neither, really. It's the Texas Border Country, where the two countries rub shoulders, occasionally jabbing elbows into each other's ribs. Geographically, the two are separated by the Rio Grande, a restless river forever changing its bed. Sometimes it trickles, and you can wade across it as a Wet-ankle. At other times it goes on rampages, washing away slices of cities. In the Big Bend, it punched gunsight notches through the Chisos Mountains. Nobody knows how.

But culturally, the Border Country is split by the profoundly opposed value systems that exist on either side of the Rio Grande, particularly from the Big Bend all the way down to Brownsville on the Gulf. The locals who straddle the river speak Tex-Mex and think schizophrenically, shifting back and forth between cultures, depending upon whether they’re talking to John Smith or Juan Mendoza.

Still, the Border Country has its own distinct flavor that attracts some people like a magnet—people such as me. So when a couple of fortunate occurrences made it both convenient and logical for me to ride a motorcycle there, I soon found myself out the road, headed for the Rio Grande.

Fortunate Occurrence One was when CYCLE fered me the use of a Yamaha V-Max and asked me to rack up some miles on it. To me, that said “touring” loud and clear. True, the V-Max is not renowned as a touring bike, but it is a descendant of a mighty good one in the Venture. Besides, riding long distances on unfaired motorcycles is one of my favorite things in life. I want to see it all—every bit of each vast panorama that opens up before me on the road. I want no fairings, no windshields, nothing to impede that view. Just me and the motorcycle and the smallest pack I can manage. 26/CYCLE

Fortunate Occurrence Two happened on a Saturday afternoon, a couple of days after CYCLE WORLD’S offer. I was reading about the Confederate Air Force, a unique organization that still flies WWII combat planes. The outfit just happens to be based in Harlingen at the southwestern tip of Texas—in Border Country. Hmmm, I thought, an unusual place to go on a tour ... an unlikely motorcycle on which to do it. Sounded to me like the makings of a perfect trip.

By Sunday morning, I had finished loading the V-Max and was ready to head out for Texas. The skies were cloudy, screaming threats of rain, but the ground was still dry. The V-Max looked squat, powerful, expensive, elegantly ugly—like my idea of a champion sumo wrestler all dressed up for a night on the town in an Yves Saint Laurent suit and Patek Phillippe wristwatch.

I punched the starter button and let the engine warm up. BU-BURBLE, BU-BURBLE. Those cams had been ground to get serious at some speed other than idle. Deep and resonant, the V-Four sounded like a Harley that had finally taken the cough medicine the doctor had been prescribing all these years.

I climbed onto the freeway and headed south toward San Diego. So did a vast number of other Angelenos in cars. Most of them were tooling along at about 65 mph, and I elected to do the same. That meant 4200 rpm in fifth, a nice idle for the V-Max. The bike was stable and predictable on the grooved freeway, and I was relaxed.

For me (5-foot-8, 1 35 pounds), the seating position was perfect; it was as if the V-Max’s designers had sent an ergonomist over to my house with tape measure and camera, and put those dimensions into production. The oddlooking saddle felt luxurious, but I’d know more about that by the end of the day. I had to lean forward to reach the stubby handlebar, but at 65 mph there was no weight on my hands because the wind-blast counterbalanced me perfectly; I even had a little bend left in my elbows. My 52year-old knee joints, which are mighty persnickety about saddle-to-footpeg geometries, also were completely satisfied with the Yamaha’s arrangement.

I pulled off to pit at the rest stop near San Onofre. Afterwards, I rumbled slowly to the end of the access road, then got it all in low and power-shifted into second. The front wheel came up, the handlebar got impatient, and before I knew it, the bike and I hurtled onto the freeway doing 75 mph in second. I slowed down and upshifted. I’d had my first brief glimpse into the true nature of the muscular Mr. Max.

At San Diego I headed east on 1-8, paralleling the Mexican border, and the highway immediately began to climb the west slope of the coastal mountains. When I stopped for gas in the town of Crest, I found I had to unhook the bungees, take my red bag off the pillion, unsnap the four connectors for the soft saddlebags, lift the bags off the seat, pull down on the latching rings to pop up the saddle step, stick the ignition key into the lock on the gas cap, take out the cap and find someplace to put it, put gas in the tank, and then go through the whole rigamarole again in reverse order. Obviously, the under-seat location of the filler tube is not the V-Max’s outstanding feature for touring purposes.

"At the motel I checked the weather, and immediately learned why / had been so miserable: I'd spent most of the day riding in 31-degree rain."

The minute I hit the freeway again, I passed an invisible boundary: The storm clouds ended and the sun shone brightly, although the air was still crisp and cool. For the next 60 miles the road would rollercoast up over passes and down into high valleys across the mountains.

I entered the Cleveland National Forest, riding amidst lots of greenery and bare rock. Here, the easternmost row of mountains in the chain seem tired. They’re soft, bare stone that has cracked and shivered and then worn rounded. The results are bizarre: big boulders balancing atop small boulders; cliffsides of rotten rock defying gravity. Had I been an Indian roaming this territory a few hundred years ago, I think I’d have figured that some really evil spirits—bad medicine—occupied this place, and I’d have stayed away.

After I wound down the twisting road coming out of the mountains, the highway straightened out, and the afternoon grew hotter as I droned across the desert. That evening, I pulled into a motel parking lot in Yuma and realized that the V-Max was about to be subjected to the acid test: After my first day (400 miles) of riding this cruiser/ hot-rod, would I wobble down off the bike, crawl off'the bike, climb off the bike, or hop off the bike? To my amazement, I hopped off. My butt wasn’t even sore, and neither were my back or my arms. The V-Max was turning out to be one plush motorcycle.

I was greeted the next morning by a spectacular view of one of Southwest Arizona’s numerous little baby-mountain ranges. It’s as if the majestic mountains elsewhere in the state had grown seeds, the wind had carried them down here, and they’re just now starting to grow. You’ll see a nice, jagged, wrinkledly mountain range that looks like it’s way out there halfway across the state, and 15 minutes later you’re riding right alongside the thing because it’s only one-fifth scale.

From 1-8 at Gila Bend, Arizona Route 85 heads south through an Air Force gunnery range, with lots of posted signs inviting you not to wander off into the countryside thereabouts, lest you fail to return. The road eases through a gap in the Specter Range—chocolatey little mountains filled with weird, miniature pinnacles and other tortured shapes sculpted by the weather from eroded lava-flows.

From Why (the town), Arizona 86 (the road) branches off Arizona 85 and wanders eastward through the Papago Reservation. There the towns have names like Gu Vo and Pan Tak. This region is a northern suburb of the Sonora Desert, and it is a cactus-lover’s paradise—giant saguaro, vicious tree-cholla, barrel, buttonhook, you name it.

The sun had shone all day long, but somebody had forgotten to turn up the thermostat, and the air was getting progressively colder. The wind had picked up, and it was buffeting my helmet as I turned my head from side to side

like a spectator at a tennis match to check out the rapidly changing panoramas of mountain ranges and valleys on both sides of the road.

At Tucson I joined I-10. Until then, I had seen no hitchhikers on the road. Then came a sign saying, “DETENTION CENTER. DO NOT PICK UP HITCHHIKERS.” For the next 10 miles it seemed there was a hitchhiker with his thumb out every hundred yards. Very few of them were kids; most were hardbitten men in their forties and fifties, shivering in the cold.

Just west of Benson I topped a rise, and there spread out in front of me was most of Southeastern Arizona. The echoes of that view were still reverberating behind my eyeballs when I stopped for the night at Willcox.

The next morning it was cold and pouring down rain. I put on my rainsuit over the rest of my clothes, lumbered into the restaurant next door, and stoked up on mountains of hot food. When I could delay no longer, I waddled outside and climbed aboard my soggy motorcycle. Five minutes down the road my gloves were sodden and my hands were cold. Ten minutes down the road my hands were soaking-wet and freezing. I was wearing two pairs of thick socks and my regular motorcycle boots, but half an hour later my feet also were congealing.

By the time I reached Sierra Blanca, Texas, I’d had enough. I pulled gingerly off the freeway, my coordination completely shot. At the motel I checked the weather, and immediately learned why I had been so miserable: I’d spent most of the day riding in 31-degree rain.

The next morning I stuck my head out the door of my room like a groundhog looking for his shadow. Hallelujah! A freezing wind and threatening skies, but no rain and no ice on the road. After breakfast, however, as I climbed on the bike, I saw a gigantic storm front sweeping down from the north. I wanted desperately to outrun it, so I left Sierra Blanca a lot faster than I had arrived. I was rapidly freezing solid, but every mile without rain was a fresh victory.

With the help of the speedy Mr. Max, I outran the front as I pressed ahead on I-10. At Fort Stockton, I turned south on a two-lane road, U.S. 285. I had been riding at about a 4500-foot elevation since Tucson, but now I was heading downhill toward Sanderson, at 3000 feet. Maybe then I could begin to thaw out.

At Sanderson I joined U.S. 90, where the air was merely cold, rather than freezing. I stuck to the border routes, touching the edge of the country at Del Rio, Eagle Pass and Laredo. Gradually, life became livable.

Before long, the sun was shining gloriously, and I started shedding clothes. The road bottomed out in the U.S. and headed east, across the tip of Texas, through the truck farms and citrus groves of the Rio Grande Valley. Finally, at Harlingen, my destination, I hunted up a motel and promptly changed into T-shirt and shorts. The temperature was a balmy 80 degrees.

RHROUGHOUT Lloyd Nolen WORLD was to fly WAR fighters II, THE in SINGLE combat, GOAL but he OF remained stuck Stateside as a flying instructor. After the war, Nolen decided that since Uncle Sam hadn’t given him a fighter to fly, he’d buy one of his own. In 1951 he collected a surplus P-40 (the Curtiss fighter made famous by the Flying Tigers), and flew it out of the cropduster field at Mercedes, a town near Harlingen.

Although glamorous, the P-40 had a notoriously underpowered Allison engine, and Nolen wanted something faster—like a P-5 1. So he sold his P-40, and in 1957, he and four friends chipped in to buy a P-5 1. Not long thereafter, in the dark of night, someone painted “Confederate Air Force” on the fuselage of that P-51. The name seemed appropriate, since the South did not then happen to have its own air force. Thus was born the CAF.

In 1958, Nolen and friends doubled the size of their fleet by buying an F8F Bearcat, the hottest Navy fighter of WWII design. After that, things rapidly got out of hand. In searching for more fighters, the CAF discovered to its amazement that the U.S. government was intent upon chopping up and melting down every single remaining WWII combat plane without even bothering to preserve one of each in flying condition. Meanwhile, into the small ranks of the CAF had come other pilots—including Marvin Gardner and Joe Jones, who decided to bankroll the purchase of one of every model of WWII U.S. fighters for the CAF, in flyable condition. Even if the government had no soul, the CAF did.

Consequently, there was some heavy iron trying to fly offthat little 3000-foot strip at Mercedes. But nearby Harlingen Air Force Base had closed down in 1966, so the CAF moved there in 1972, and rechristened the airbase “Rebel Field.”

I pulled into the last empty parking slot in front of CAF headquarters, and after paying my admission, walked out to the flight line and studied the old airfield. The long runways out there seemed to be the only parts of it that I could still recognize.

Yes, I had been here before. In 1953 this had been an Air Force training base for navigators/bombardiers/radar observers, and I had been stationed here as an Aviation Cadet. Since then, both Harlingen Air Force Base and I had changed considerably.

The aircraft were parked in two large hangars. Spitfire, P-51, P-40, Bf 109—as a youth during the war I had watched them in the newsreels, and to me they will always remain the sleekest, deadliest aircraft of them all. I had visited aircraft museums before, but this was a flying museum: pools of oil beneath the fuselages, maintenance stands, chain hoists used for lifts. A P-47 stood there with an empty nose, its Pratt «fe Whitney R-2800 engine off getting an overhaul. These are planes that fly.

Most of the people walking around in the hangars appeared to be in their sixties. And they remembered. As I stared at a TBF (Grumman Avenger torpedo bomber), one of them said, “You know, the only difference I ever found between that airplane and the General Motors TBM version was that the fuel-line fittings were flareda little differently, and the threads had a slightly different pitch. And that was 40 or 45 years ago.

There were several medium bombers in various stages of restoration, and a B-24 out on the hardstand. I asked one of the staff where the B-17 and the B-29 were. He said, “Oh, this place is just headquarters for the CAF. We have other wings scattered all around. Most of 'em fly in our other aircraft once a year to raise hell in the Airshow,’ when we re-create the bombing of Pearl Harbor. There’s ‘bombs’ going off, and dogfights, and bombers getting shot up. People come from all over the world to watch it.

"The V-Max looks like a badass bike, sounds like a badass bike, is a badass bike. But it was a joy for me to ride for days on end."

The CAF also has a museum, in which are displayed the uniforms and paraphernalia of air crews from the warring nations. I looked at aerial torpedoes, ancient radios, an E6B computer . . . and then I saw a Norden bombsight. Instantly, I flashed back to my Cadet days at Waco, where I rode in the plexiglas nose of a B-25J medium bomber, theoretically rocketing along at least 300 feet off the deck (although we sometimes brought back leaves in the wheel wells), frantically trying to line up checkpoints in the Norden sight for a straight run in to the target as the world tore past so close beneath my feet.

/CRUISED AROUND HARLINGEN IN T-SHIRT AND SHORTS

until it was time to leave. The reason I knew it was time to leave was that a storm front came in to escort me out of town. So I saddled up and headed west in a cold drizzle, which at times changed into thunderstorms to relieve the monotony.

In Laredo I learned that a snowstorm was blanketing West Texas, so I decided to forego that pleasure. Instead, I puttered around Laredo, exploring such historic sites as the Nuevo Santander Museum. After a day or so, the storm ended, I left Laredo, and the temperature plummeted. At Eagle Pass it bottomed out at 30 degrees, and I thought, “Eve seen this movie, too.”

U.S. 90 was almost empty, except for roadrunners whizzing across the highway in front of me. If I closed too fast, they'd throw in a little wing-flapping to help out their blurring legs—like afterburners. And on U.S. 285, the wind sent me tumbleweeds. That was okay, until a fourfoot tumbleweed stopped in the road dead ahead of me. I wasn’t at all sure what happens when you run into a fourfoot tumbleweed at 85 or 90, and I didn’t want to find out, so I invented a line around it.

On I-10 the next morning the wind had died, but the temperature was still hanging in the low 30s. Past Tucson, the sun quit being a decorative ornament and started radiating heat, so I shed a ton of clothing and became a real

motorcycle rider again.

On Arizona 86 I overtook a long string of motorhomes and campers, just as we met another string heading toward us. I dropped the V-Max into fourth, and every time there was a gap bigger than a heartbeat, I passed. But on the powerful V-Max, it was more like weaving than passing. I would watch radiator grills grow rapidly larger as I hurtled toward them before jumping hard on the brakes, whipping into an empty slot in my own lane as the other vehicle went by, then instantly diving out into the left lane again.

Just on the other side of Yuma, the air grew cold and wet and heavy . . . and then came the rain. Past Ocotillo, where the road begins to climb the west side of the coastal mountains, the rain became a torrential downpour.

By then, I was riding in such heavy clouds that I could only see about 50 yards ahead, and gale-force wind gusts were making matters even worse on the mountain curves. I tried slowing down to 50, but a string of campers always would creep up, pass me, and then hang there in the left lane just ahead, blinding me completely. I tried speeding up to 70, which enabled me to pass the campers quickly, but then the winds would blow the V-Max around like a 1200cc kite. What with continuously wiping my faceshield, continually working the handlebar to try to keep the raging winds from blowing me off the road, and trying to peer through the fog to figure out which way the road went next, I was about as busy as I have even been in the saddle of a motorcycle.

I was at a loss about what to do when I saw a sign that said, “Food Next Exit.” Without hesitation, I charged down the off-ramp and into the parking lot of the resort motel responsible for that sign. After a cheeseburger and about six cups of coffee, I plugged myself back into my wet leathers and rainsuit (not even a full can of Scotchgard could stand up to such rain), and unenthusiastically went back to play in the madness on the freeway.

This time I rode at 50. As I crested the last set of mountains and started down toward San Diego, the rain had finally stopped.

The freeway heading north to Los Angeles held amazingly little traffic for a Saturday afternoon. By then I was seeing the world in a haze, because Ed frosted my faceshield by scrubbing it so often with my glove in the mountains. No matter; in an hour and a half, Ed be home.

RATIONAL PERSON MIGHT WELL ASK WHAT ENJOY -ment such a ride could possibly have provided. But if he were to ask me, Ed have to answer, “A lot.” For me, the trip to Harlingen was a great ride because it was adventure of one sort or another every step along the way—and because I had such an outstanding bike for the trip. The V-Max looks like a badass bike, sounds like a badass bike, is a badass bike. But it was a joy for me to ride for days on end. Not once did I end a day’s journey with sore arms (or legs, or back, or butt). The bike was a big pussycat, no matter what the quarter-mile numbers might say.

So you touring riders can have your BMWs, Gold Wings, Ventures, Cavalcades—fine bikes all. Ed be content to spend my days cruising the countryside aboard a VMax, traveling light. And if the trusty Mr. Max would take me to the Border Country every once in awhile, Ed be a happier man for it. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

November 1986 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

November 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1986 -

Roundup

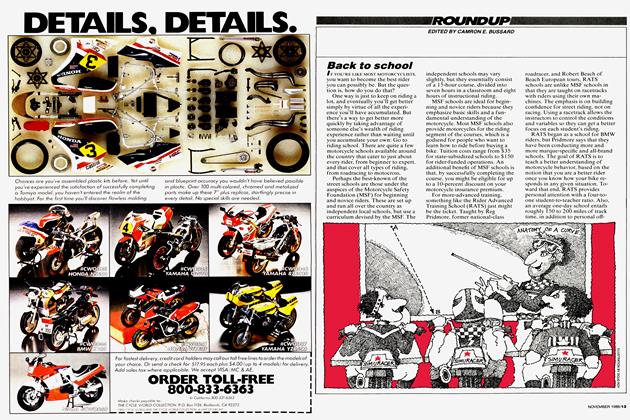

RoundupBack To School

November 1986 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

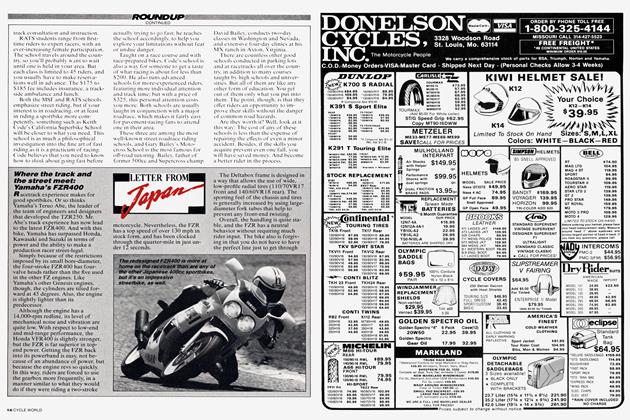

RoundupLetter From Japan

November 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

November 1986 By Alan Cathcart