YANKEE INGENUITY

In pursuing his dream, John Taylor forever altered the off-road riding habits of an entire nation

FRANK CONNER

LACONIA, 1965. IT WAS MIDNIGHT, AND WE WERE DOGtired. John Taylor was driving, and I was thinking about the motel bed waiting for me just down the road. For the past 16 hours, we had been running the Bultaco booth at the motorcycle show.

Then a state trooper flagged us down. "Riot up ahead!" he said. And there it was, straddling the only road to our motel. We sat glumly in the car and watched National Guardsmen shoot rock salt from their pump shotguns at the rioters, while the rioters threw rocks and beer bottles at the National Guard.

“Now what’ll we do?”I asked.

“We gotta get some sleep,” said John. “We can’t drive through there, but we could walk right down the middle of the road.”

That caught me off-guard. I’d been in several riots before—on the side of The Law—and once or twice had escaped death or serious injury by a slender margin. “We’ll be right in the line of fire,” I said.

“Doesn’t matter,” replied John. “We’re the twentiethcentury version of knights in armor: We’re wearing business suits and carrying attaché cases. They won’t touch us. Let’s go.”

Seconds later, we were strolling down the road dangling our attaché cases, seemingly deep in conversation. As we passed, the Guardsmen stopped shooting their shotguns to let us go by, and the rioters stopped throwing bottles; once we were clear, all hell broke loose again behind us. John wasn’t about to let a little thing like a riot keep him from his bed.

Now, understand that John Taylor was not—and still is not—a physically intimidating person. He wore powerful glasses that magnified his eyes, and he had an unprepossessing chin. He dressed quietly, and would quickly disappear in a group. But he was a fiercely determined man. And in pursuing his motorcycling dream, he did much to change the riding habits of the nation.

In the 1950s, John made a living by selling machine tools to factories in and around Schenectady, New York. His hobbies involved sophisticated machinery—cars, cameras, sound systems and motorcycles. When buying hi-fi gear, he would infiltrate the New York dealer trade show, play the equipment loud with the controls set flat, and listen. He didn’t care about the brand name, just the sound. And he would buy the very best equipment available. His idea of a good camera was a Hasselblad with the hand-ground Kodak lenses. He traded cars every six months—Ferraris, Lancias, Cunninghams. He’d drive a car and learn all its tricks, then sell it at a profit and buy another.

Taylor also was a born trail rider. He loved to attack the rocky, washed-out trails in Northeastern New York, around Sleeping Beauty Mountain near Lake Georgesome of the prettiest country in the United States. He liked to go fast, but he also liked to take in the scenery.

Trail riders of that era routinely plowed through the back country aboard 500cc Triumph TR-5s, 45-inch KModel Harleys and BSA Gold Stars. But those motorcycles left a lot to be desired in the woods, because basically, they were streetbikes. The engine tune was wrong. The gearbox ratios were too few and far between. The steering could get squirrelly in the dirt. The suspensions averaged only around 3 inches of travel. But those bikes were about all you could get.

What Taylor wanted was a true dual-purpose 500cc motorcycle with a wide powerband, one that was fast but had enough torque to loft the front wheel over logs and climb steep hills from a standing start. He wanted a bike that was light but rugged, that had quick steering but was stable on tricky terrain. Sort of a vastly updated TR-5. Trouble was, John wanted all that in the 1950s.

Back then, the real improvements in off-road bikes were being made by European manufacturers, usually for their International Six Days Trial (ISDT) works prototype machines. A few companies, like MZ and Greeves, were doing some interesting things with chassis, while also slowly refining the lowly two-stroke engine. By experimenting with carburetion, combustion chambers, port timing and exhaust-pipe tuning, they could squeeze a considerable amount of power out of a small-displacement two-stroke engine for all-out racing purposes; or they could detune it to suit the precise needs of the serious trail rider.

25TH ANNIVERSARY

But the one thing they couldn’t deliver was a two-stroke engine with a displacement greater than 250cc. It was an article of faith among motorcycle designers that twostroke engines bigger than 250cc would constantly—and inevitably—seize.

But Taylor believed that the 250cc trailbike was not the answer. To get a decent power-to-weight ratio, the bike had to be so light that it was too fragile. And even then, a 250cc engine tuned for fairly fast trail-riding didn’t crank out enough power to yank the front wheel up over logs. To get that capability, the designer had to shove the engine way back in the frame, which meant that the front end was too light, making the bike unstable. And if the engine was tuned for maximum horsepower, the rider had to shift gears constantly to keep the engine revving up on the pipe.

To John, the real solution would be a 500cc two-stroke dual-purpose production bike incorporating the best features of the lightweight ISDT prototypes—but upscaled. He was almost alone in his conviction that the magic 250cc displacement-limitation for high-performance twostroke engines was like the sound barrier for aircraft: inviolable until broken. Still, nobody was manufacturing the bike he wanted; obviously, what he had to do was get somebody to build it.

In 1962, John learned that the East Coast distributorship for Bultaco motorcycles was up for grabs. These highperformance, two-stroke Spanish motorcycles were available in displacements ranging from 125cc to 200cc. The Bultaco line consisted of TSS production roadracers, Sherpa S scramblers, Sherpa T trials bikes, and some of the best-handling street machines in the world. John got in touch with the Compania Española de Motores

(CEMOTO) in Barcelona, and cut a deal with the owner, F.X. Bulto, to become the eastern distributor for Bultaco motorcycles.

John went into business by uncrating his first Sherpa S, taking it to the local scrambles track and racing it. The other riders got the message instantly. You don’t have to advertise a winning competition motorcycle. Soon, he was getting all the orders his fledgling company could handle. He sold machine tools by day, and ran the CEMOTO East Importing Company at night (with a lot of help from his wife Kay). The business quickly outgrew John’s spare time, so he took the big jump and quit the machine-tool business. He may have been badly undercapitalized, but at least he was smack in the middle of the motorcycle business.

Abruptly, the game changed. Dirt bikes were becoming glamorous, so the Japanese began selling vast quantities of things called street scramblers—350-pound street motorcycles with high pipes, high fenders, knobby tires and evil handling. They combined all the disadvantages of a mediocre streetbike and a mediocre dirt bike, and few of the advantages of either. But they looked mean, so they sold like hotcakes to the hordes of new riders in the market.

Since that was the going trend in dirt bikes, the western Bultaco distributors persuaded CEMOTO to put a Spanish version of a street scrambler into production. CEMOTO asked John if he’d like some of them to sell in the East, but he declined.

Instead, John compiled all the specifications he thought would make for an ideal trailbike, committed them to paper and sent them to CEMOTO. And while Mr. Bulto wasn’t exactly ecstatic about the concept, he did promise Taylor that he’d have the company “work on it.’’ John hoped that promise was a sincere one, for he believed that such a bike was necessary for his survival as a distributor of Bultaco motorcycles.

In December of 1963, Taylor flew to Barcelona to test a 200cc prototype of his proposed trailbike. In a pure stroke of luck, that area of Spain had just received one of its rare snowfalls, making the normally hard, dry ground quite slippery and treacherous—a perfect test of the tractability and ridability of a bike intended for enduro use. After a day’s ride, John thought the prototype was fantastic, just the kind of machine he was looking for. And somehow, the silver-tongued Taylor talked Bulto into letting him take that very prototype—the only example of that bike in existence-back to the U.S. with him, so he could try it on his favorite trails and verify its competence.

Verify it he did. He then sent CEMOTO a large order for a production version, to be called the 200cc Matador. But because John had the only prototype in existence, CEMOTO had to build the first production Matadors using only photographs and an incomplete set of drawings.

I showed up at John’s doorstep shortly thereafter. We knew each other slightly; I’d been campaigning a 200cc TSS roadracer that year, and John had sold me spares at various racetracks around the country. I desperately needed a shop manual for the TSS, but none existed. So John arranged to have his service manager pull my bike apart and put it back together in my presence, while I took notes and shot photos. Before my visit was over, though, I had not only a shop manual, but a new job as John’s advertising writer and bookkeeper. For five years, I worked for him in one capacity or another.

John had taken the first step toward his dream; he had a good lightweight trailbike in the 200cc Matador. For the second step, he met with Bulto and asked for a 350cc version of the Matador. John was inching closer to his 500cc super enduro-bike.

Soon, the 200 Matador was upgraded to 250cc; but the 350cc version wasn't getting off the ground. Part of the fault was ours, for we had the tiny Bultaco factory producing more models than anybody else but Honda. The strain was just too great. CEMOTO didn’t even have time to debug the bikes it already was producing, much less develop a 350.

But remember, John Taylor is a determined man. And when he observed that the British motorcycle empire was faltering, he thought maybe he could dovetail enough of the pieces together over there to build a 500cc two-stroke enduro machine. So he sent his service manager, Jess Thomas, on an investigative trip to England.

Thomas returned absolutely appalled. British industry was in such internal turmoil that it was slowly coming apart at the seams. Obviously, England was not the place to build Taylor’s dreambike.

But John wasn’t out of tricks. Not yet. He learned that Ford Motor Company’s manufacturing permit in Spain had been revoked for political reasons a few years earlier, and that the company was interested in somehow getting back into that country. So he met with F.X. Bulto and found that CEMOTO had an automobile-manufacturing permit it had never used, and that Bulto was willing to sell the company—permit included—to John. John then went to Ford’s top brass and made them a proposition they found quite intriguing: If Ford would give John a longterm loan for $300,000, in return he would give them CEMOTO’s permit to manufacture automobiles in Spain.

John’s thinking was that if he owned the Bultaco factory, he could develop the 350cc off-road bike right away, and follow it up with a 500 as soon as possible. And the $300,000 loan would serve as the capital he would need to run the factory after spending a sizable chunk of money to buy it.

OnceFord figured out thewhysand wherefores of how to loan someone money—a type of transaction that company was not accustomed to handling—the deal was set to go through. But once again, fate—this time in the form of a massive United Auto Workers strike—threw a monkey wrench in the works. Ford’s top management felt that the strike was likely to go on without end; so in anticipation of vastly reduced profits, they cancelled all long-term projects, including the proposed loan/permit-exchange with John Taylor. End of deal.

As a result of all these setbacks in John’s plan to sell an intermediate-size enduro bike, other manufacturers ultimately beat him to the punch with such machines. Husqvarna in particular made a big impact on the market with a 360cc single-cylinder two-stroke enduro. Eventually, Bultaco did produce a 360cc enduro bike, but by then, nobody paid much attention.

Still, no one was yet building a 500cc two-stroke enduro machine. John concluded that if he ever were to have his big enduro, he’d have to build it himself. But there were two serious obstacles in his path: l) In this country, there were almost no suppliers of the kinds of off-road motorcycle components John needed, and it would take too long to develop them from scratch; and 2) setting up an engine-manufacturing facility would cost far more money than John had at his disposal. Obviously, he would have to buy major chassis components (forks, shocks, electrics, etc.) from overseas vendors, and buy engines built to his specs by some other manufacturer. But who? He went shopping.

Daytona, 1966. John and I met Manuel Giro, who ran Maquinaria Cinematográfica, another company based in Barcelona. Giro’s operation built theater-type motion-picture projectors for the European market, and OSSA motorcycles. Giro told us he had tried selling OSSAs through a network of U.S. distributors, but didn’t think that a bunch of small operations could do the job. He instead wanted a single U.S. distributor.

In a follow-up meeting later that same year, Giro asked John if he would become the sole U.S. distributor for OSSA. And as an added incentive, he made an offer that stunned both John and me: If John would take on OSSA, Giro would custom-design and build an engine just for us. What shocked us was that in our previous meeting with Giro, we had not said a word about Taylor’s desire to build a big two-stroke enduro bike. John thought about the offer—but not for very long—and made his only major stipulation: He would own the final engine design, not OSSA. Giro agreed, and the deal was consummated. John’s dream finally looked like it might become reality.

Quickly, John started a new firm (that was totally sepa-

rate from his CEMOTO East operation, even though it was in the same building) dedicated to the design and fabrication of his dreambike. He already had decided that the machine would be called the Yankee, and named his new operation Yankee Motor Company.

At first, John set up the OSSA distributorship in Houston, Texas, so it would be more centrally located than in Schenectady. I was put in charge of the operation, and went to work writing much-needed manuals and building a solid dealer network. After little more than a year, however, John relocated the OSSA distributorship in Schenectady. His arrangement with OSSA had not pleased Mr. Bulto, and had led to John’s sale of CEMOTO East to the Bultaco factory. And when the new CEMOTO East management moved the entire Bultaco operation a few miles down the road, John suddenly had sufficient office and warehouse space in Schenectady to put OSSA and Yankee under one roof.

By now, John really was in hot pursuit of his dream. He had determined that the Yankee would be powered by a 460cc two-stroke Twin, using two OSSA 230cc top-end assemblies mated to entirely new crankcases. Both cylinders would fire simultaneously, giving the overall effect of a big Single, but with even more power, since two cylinders yield more total piston surface area than one cylinder. The engine would be tuned for bottom-end and mid-range torque, giving an extremely wide powerband. With a wideratio, six-speed gearbox and stock gearing, it would be able to tractor along at one mph, or top out at 95. And during the bike's developement, 250-class OSSAs were enlarged to 244cc, thus the Yankee became a 488, making it even more powerful.

John hired Dick Mann to design the frame and steering geometry. Aside from being a former AMA National Champion, Mann had ridden more makes and models of competition motorcycles than just about anybody else in the U.S. And stored away in his mind were the frame specs, steering geometries and handling characteristics of each of those bikes. He was the perfect choice for the job.

Mann worked out a frame design that put the engine fairly far forward in the frame, to give John the weight he wanted up front for good front-wheel traction (with this engine, lofting the front wheel would be no problem). That arrangement allowed Mann to run the lower framerails close together where it counted—at the footpeg mounts. John wanted a bike that was large in displacement, not in width.

John opted for a contemporary motorcycle design, but one built of top-quality materials. The frame would be TIG-welded by hand, using thinwall 4130 chrome-molybdenum steel tubing and plate. The fork triple-clamps would be made of aircraft-quality forged aluminum alloy. The swingarm bearings would be monofilament-wound, and the bike would wear a disc brake on the rear wheel (but not up front, because most riders feared a front disc would be too powerful on dirt). The result would be an understated, no-frills enduro bike for riders who valued quality over gadgetry.

When a few early engines arrived from Barcelona, Yankee Motors built prototypes, tested them, and loaned them to the motorcycle magazines, who were so impressed with the potential of the machine that they wrote about it fulsomely. Then disaster struck. There was an unaccountably long delay of several years in the shipment of production engines. And numerous vendors of chassis components either were unable to produce acceptable goods, or failed to deliver on time. Consequently, John discovered what the Auburn Motor Company had learned with the Cord automobile in the 1930s: If you tantalize ’em with the prototype but don’t deliver the product right away, public interest dies dead, never to be revived.

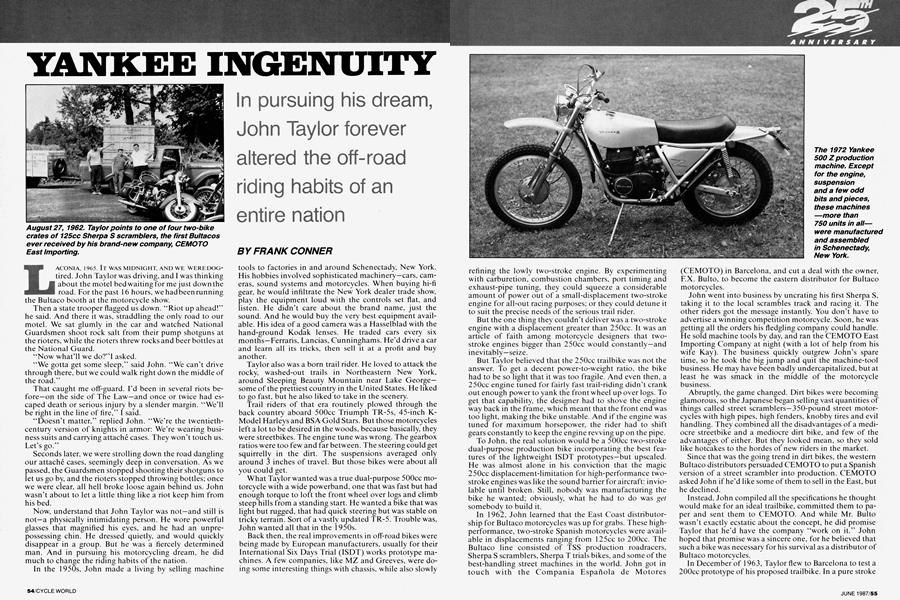

But John persevered. And in 1972, the Yankee 500 Z finally made it into production. It was a bike you could ride on the highways (across the state, if necessary) to get to the good trails, without beating yourself to death en route. No need for a pickup to haul it. Once there, you were equipped to charge whatever obstacles Mother Na-

ture had seen fit to provide along the trails.

At first glance, the 335-pound Yankee seemed a formidable machine to take into the wilderness. But you didn’t have to muscle the Yankee; you could steer it with the throttle. It had such good throttle response and so much torque that you could just let the engine do the work. And with all its power, it could easily climb hills that most 250s wouldn’t get halfway up, usually without even cranking very hard in second or third gear. Everything seemed to happen more slowly on a Yankee; you could ride rocky trails at a pretty good clip, and even look at the scenery as it went by.

John had accomplished exactly what he set out to do. He had updated the Triumph TR-5.

But by the time John had the bike, he no longer had the market. The guys who had paddled their TR-5s and KModels and Goldies through the woods, with gritted teeth and prayer in their hearts as they breathed the odor of frying clutch, had vanished into the mists of time by 1972.

Instead, the off-road standard had become the Matadorinspired enduro bike: a 250cc two-stroke Single that weighed around 250 pounds. But John was offering the riders a 335-pound 500 Twin. Their reaction was, “God, what an elephant; why would anybody want a bike like that when they can buy a neat little 250?” So in the end, John had done too good a job of introducing the ISDT bike to America. Now America had it. and couldn’t see beyond it.

Quickly and quietly, then, the Yankee faded into obscurity. As an idea, it had been way ahead of its time; but when the idea finally became reality, it was too far behind the times.

The January issue of CYCLE WORLD tells me that John is now living in Fallbrook, California, and is about to invade the hi-fi consumer market by manufacturing ultra-hightech sound equipment—under the name “Yankee.” If the equipment I used to listen to in John's home 25 years ago is any indicator, the results should be spectacular. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialA Crash Course In Career Counseling

June 1987 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeMil-Spec Motorcycling

June 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Shape of Things To Come

June 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

June 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

June 1987 By Alan Cathcart