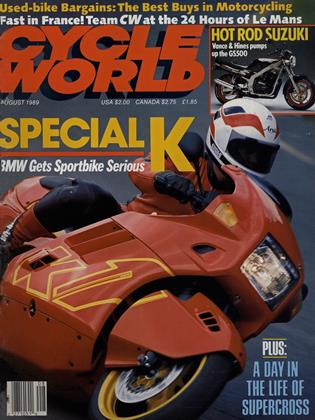

SUPERCROSS 101: A PRIMER

BLAME IT ON MIKE GOODWIN.A LONG TIME AGO, motocross was motocross. It wasn’t sophisticated, clean or easy; it was just tough. Then Goodwin dumped some dirt on the floor of the Los Angeles Coliseum, ran a race on it and called it supercross. Nothing has been the same since.

Supercross requires a different riding style, a different technique and a different attitude from the rider than does conventional outdoor motocross. And, as the factories soon discovered, supercross also requires different machinery.

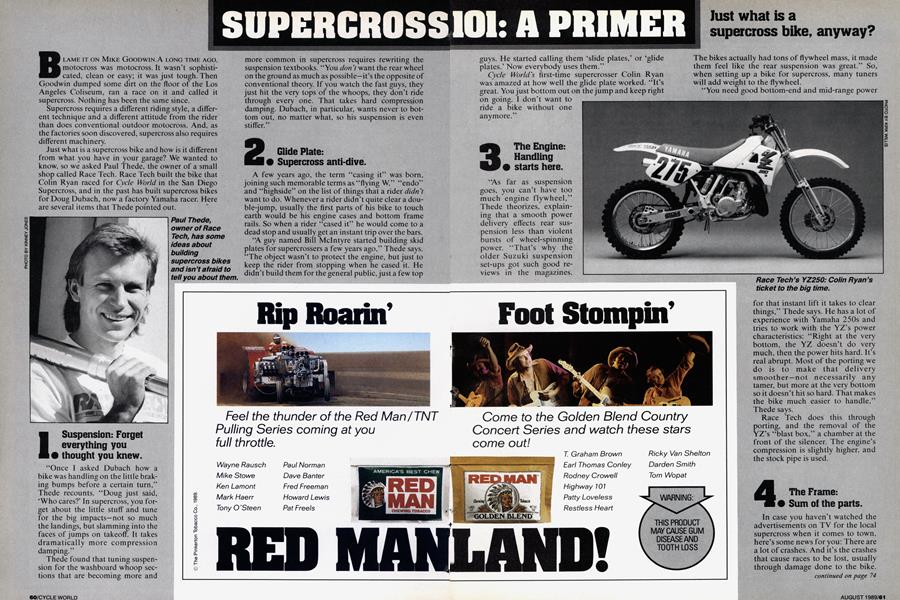

Just what is a supercross bike and how is it different from what you have in your garage? We wanted to know, so we asked Paul Thede, the owner of a small shop called Race Tech. Race Tech built the bike that Colin Ryan raced for Cycle World in the San Diego Supercross, and in the past has built supercross bikes for Doug Dubach, now a factory Yamaha racer. Here are several items that Thede pointed out.

1. Suspension: Forget everything you thought you knew.

“Once I asked Dubach how a bike was handling on the little braking bumps before a certain turn,” Thede recounts. “Doug just said, ‘Who cares?’ In supercross, you forget about the little stuff and tune for the big impacts-not so much the landings, but slamming into the faces of jumps on takeoff. It takes dramatically more compression damping.”

Thede found that tuning suspension for the washboard whoop sections that are becoming more and more common in supercross requires rewriting the suspension textbooks. “You don't want the rear wheel on the ground as much as possible—it’s the opposite of conventional theory. If you watch the fast guys, they just hit the very tops of the whoops, they don’t ride through every one. That takes hard compression damping. Dubach, in particular, wants never to bottom out, no matter what, so his suspension is even suffer.”

2. Glide Plate: Supercross anti-dive.

A few years ago, the term “casing it” was born, joining such memorable terms as “flying W,” “endo” and “highside” on the list of things that a rider didn't want to do. Whenever a rider didn’t quite clear a double-jump, usually the first parts of his bike to touch earth would be his engine cases and bottom frame rails. So when a rider “cased it” he would come to a dead stop and usually get an instant trip over the bars.

“A guy named Bill McIntyre started building skid plates for supercrossers a few years ago,” Thede says. “The object wasn't to protect the engine, but just to keep the rider from stopping when he cased it. He didn’t build them for the general public, just a few top guys. He started calling them ‘slide plates,’ or ‘glide plates.’ Now everybody uses them.”

Just what is a supercross bike, anyway?

Cycle World's first-time supercrosser Colin Ryan was amazed at how well the glide plate worked. “It’s great. You just bottom out on the jump and keep right on going. I don't want to ride a bike without one anymore.”

3. The Engine: Handling starts here.

“As far as suspension goes, you can’t have too much engine flywheel,” Thede theorizes, explaining that a smooth power delivery effects rear suspension less than violent bursts of wheel-spinning power. “That’s why the older Suzuki suspension set-ups got such good reviews in the magazines. The bikes actually had tons of flywheel mass, it made them feel like the rear suspension was great.” So, when setting up a bike for supercross, many tuners will add weight to the flywheel.

“You need good bottom-end and mid-range power for that instant lift it takes to clear things,” Thede says. He has a lot of experience with Yamaha 250s and tries to work with the YZ’s power characteristics: “Right at the very bottom, the YZ doesn’t do very much, then the power hits hard. It’s real abrupt. Most of the porting we do is to make that delivery smoother—not necessarily any tamer, but more at the very bottom so it doesn’t hit so hard. That makes the bike much easier to handle,” Thede says.

Race Tech does this through porting, and the removal of the YZ’s “blast box,” a chamber at the front of the silencer. The engine’s compression is slightly higher, and the stock pipe is used.

4. The Frame: Sum of the parts.

In case you haven't watched the advertisements on TV for the local supercross when it comes to town, here’s some news for you: There are a lot of crashes. And it’s the crashes that cause races to be lost, usually through damage done to the bike. That’s why it pays to run strong handlebars like a set of aluminum Renthals. That’s why the frames are gusseted at major stress points.

continued on page 74

continued from page 61

Thede takes precautions to prevent the crashes in the first place. He welds a small guard over the top of the rear brake pedal, so when the rider is flopping and bouncing through the stutter bumps, his foot won’t accidentally land on the brake. He also puts a thin coat of grease on the handlebar under the throttle twist grip—most mechanics won't do this for fear that it will gum up the throttle action. Thede says that a dry throttle will snap back just fine in the garage, but when a rider has all of his weight on the handlebar, the grip tends to turn with difficulty.

Of course, most of these theories and tips hold true in any type of ofifroad racing. But in supercross the stakes are higher and the consequences of any mistake are greater. Likewise, the benefits of the right kind of preparation are greater. It simply shows that while motocross is still motocross, supercross has become something else entirely. And exactly what that is, a few people like Thede are only now figuring out.

Ron Lawson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

August 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

August 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

August 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupNew, Top-Secret Triumph Revealed

August 1989 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupFor Japan Only: the High-Tech 250s

August 1989 By David Edwards