VIRGINIA CITY AND THE SUZUKI RMX250

OR, WHY I SUPPORT NUCLEAR TESTING IN NEVADA

BRIAN CATTERSON

THE INVITATION READ innocently enough: “Please come to Nevada as a guest of the Western States Racing Association,” wrote club member Edd Price, “and participate in the 22nd annual Virginia City Grand Prix. It would be a great way to test a bike.”

Hey, Price is right, I thought, and the 1992 Suzuki RMX250 in the CW garage would be perfect. I accepted the invitation.

The Virginia City GP is a notorious off-road race, renowned for its dust and rocks. In fact, it’s so dusty that the first spot on the starting grid is auctioned off each year, with the proceeds given to local charities. Someone paid $800 for next year’s lead position!

Still, I had confidence. Price told me I’d be starting on the fifth row; how bad could it be? As it turned out, worse than I possibly could have imagined.

On the day of the race, 300-plus riders grid on a city street for the 9 a.m. start, flagged off in groups of 10 at 15-second intervals. Next to me is Ron Lawson, cx-Cycle World staffer, now editor of Dirt Bike magazine. The green flag waves and I get a killer start, following Lawson into the first turn. Lawson has won a silver medal in the ISDE, I remind myself, so if I can keep him in sight for even a little while, I’ll be off to a good start.

A few seconds later, I could care less about Lawson; I’m concentrating on keeping the course in sight. As I leap off a blind jump, the entire world disappears before my eyes, blanketed by dust thicker than any fog I’ve ever seen (and I was born in New England). It’s so dense I can’t see my own handlebar ends.

I’m a roadracer at heart, not used to riding by Braille, so I hang back a little, hoping for the dust to settle. Trouble is, whenever I hang back, I get passed. I started on number 51, but before long I’m being passed by riders with numbers in the low 300s.

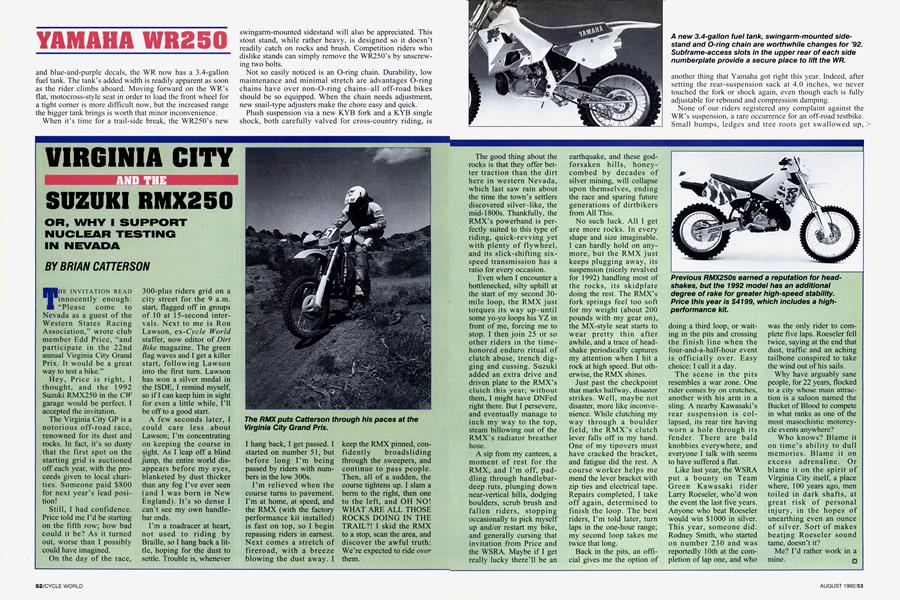

I’m relieved when the course turns to pavement. I’m at home, at speed, and the RMX (with the factory performance kit installed) is fast on top, so I begin repassing riders in earnest. Next comes a stretch of fireroad, with a breeze blowing the dust away. I keep the RMX pinned, confidently broadsliding through the sweepers, and continue to pass people. Then, all of a sudden, the course tightens up. I slam a berm to the right, then one to the left, and OH NO! WHAT ARE ALL THOSE ROCKS DOING IN THE TRAIL?! I skid the RMX to a stop, scan the area, and discover the awful truth: We’re expected to ride over them.

The good thing about the rocks is that they offer better traction than the dirt here in western Nevada, which last saw rain about the time the town’s settlers discovered silver-like, the mid-1800s. Thankfully, the RMX’s powerband is perfectly suited to this type of riding, quick-revving yet with plenty of flywheel, and its slick-shifting sixspeed transmission has a ratio for every occasion.

Even when I encounter a bottlenecked, silty uphill at the start of my second 30mile loop, the RMX just torques its way up-until some yo-yo loops his YZ in front of me, forcing me to stop. I then join 25 or so other riders in the timehonored enduro ritual of clutch abuse, trench digging and cussing. Suzuki added an extra drive and driven plate to the RMX’s clutch this year; without them, I might have DNFed right there. But I persevere, and eventually manage to inch my way to the top, steam billowing out of the RMX’s radiator breather hose.

A sip from my canteen, a moment of rest for the RMX, and I’m off, paddling through handlebardeep ruts, plunging down near-vertical hills, dodging boulders, scrub brush and fallen riders, stopping occasionally to pick myself up and/or restart my bike, and generally cursing that invitation from Price and the WSRA. Maybe if I get really lucky there’ll be an

earthquake, and these godforsaken hills, honeycombed by decades of silver mining, will collapse upon themselves, ending the race and sparing future generations of dirtbikers from All This.

No such luck. All I get are more rocks. In every shape and size imaginable. I can hardly hold on anymore, but the RMX just keeps plugging away, its suspension (nicely revalved for 1992) handling most of the rocks, its skidplate doing the rest. The RMX’s fork springs feel too soft for my weight (about 200 pounds with my gear on), the MX-style seat starts to wear pretty thin after awhile, and a trace of headshake periodically captures my attention when I hit a rock at high speed. But otherwise, the RMX shines.

Just past the checkpoint that marks halfway, disaster strikes. Well, maybe not disaster, more like inconvenience. While clutching my way through a boulder field, the RMX’s clutch lever falls off in my hand. One of my tipovers must have cracked the bracket, and fatigue did the rest. A course worker helps me mend the lever bracket with zip ties and electrical tape. Repairs completed, I take off again, determined to finish the loop. The best riders, I’m told later, turn laps in the one-hour range; my second loop takes me twice that long.

Back in the pits, an official gives me the option of

doing a third loop, or waiting in the pits and crossing the finish line when the four-and-a-half-hour event is officially over. Easy choice: I call it a day.

The scene in the pits resembles a war zone. One rider comes by on crutches, another with his arm in a sling. A nearby Kawasaki’s rear suspension is collapsed, its rear tire having worn a hole through its fender. There are bald knobbies everywhere, and everyone I talk with seems to have suffered a flat.

Like last year, the WSRA put a bounty on Team Green Kawasaki rider Larry Roeseler, who’d won the event the last five years. Anyone who beat Roeseler would win $1000 in silver. This year, someone did: Rodney Smith, who started on number 230 and was reportedly 10th at the completion of lap one, and who

was the only rider to complete five laps. Roeseler fell twice, saying at the end that dust, traffic and an aching tailbone conspired to take the wind out of his sails.

Why have arguably sane people, for 22 years, flocked to a city whose main attraction is a saloon named the Bucket of Blood to compete in what ranks as one of the most masochistic motorcycle events anywhere?

Who knows? Blame it on time’s ability to dull memories. Blame it on excess adrenaline. Or blame it on the spirit of Virginia City itself, a place where, 100 years ago, men toiled in dark shafts, at great risk of personal injury, in the hopes of unearthing even an ounce of silver. Sort of makes beating Roeseler sound tame, doesn’t it?

Me? I’d rather work in a mine. □