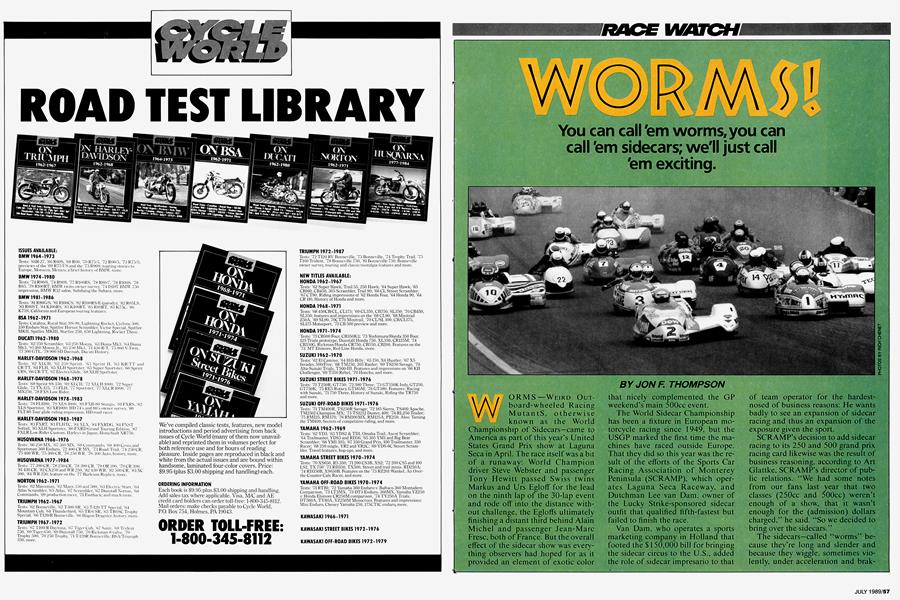

WORMS!

RACE WATCH

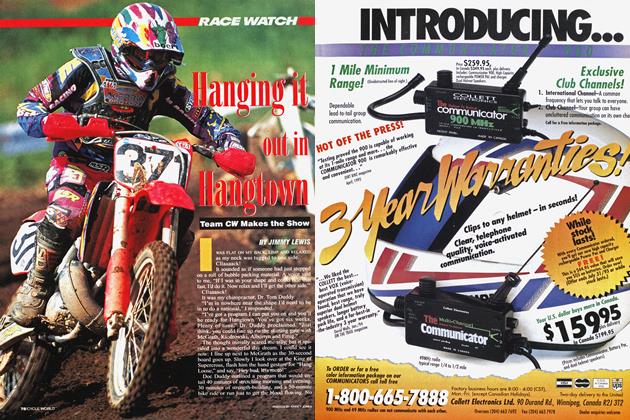

You can call'em worms, you can call'em sidecars; we'll just call 'em exciting.

JON F. THOMPSON

WORMS-WEIRD OUT-board-wheeled Racing MutantS, otherwise known as the World Championship of Sidecars—came to America as part of this year’s United States Grand Prix show at Laguna Seca in April. The race itself was a bit of a runaway: World Champion driver Steve Webster and passenger Tony Hewitt passed Swiss twins Markus and Urs Egloff for the lead on the ninth lap of the 30-lap event and rode off into the distance without challenge, the Egloffs ultimately finishing a distant third behind Alain Michel and passenger Jean-Marc Fresc, both of France. But the overall effect of the sidecar show was everything observers had hoped for as it provided an element of exotic color that nicely complemented the GP weekend’s main 500cc event.

The World Sidecar Championship has been a fixture in European motorcycle racing since 1949, but the USGP marked the first time the machines have raced outside Europe. That they did so this year was the result of the efforts of the Sports Car Racing Association of Monterey Peninsula (SCRAMP), which operates Laguna Seca Raceway, and Dutchman Lee van Dam, owner of the Lucky Strike-sponsored sidecar outfit that qualified fifth-fastest but failed to finish the race.

Van Dam, who operates a sports marketing company in Holland that footed the $ 150,000 bill for bringing the sidecar circus to the U.S., added the role of sidecar impresario to that of team operator for the hardestnosed of business reasons: He wants badly to see an expansion of sidecar racing and thus an expansion of the exposure given the sport.

SCRAMP’s decision to add sidecar racing to its 250 and 500 grand prix racing card likewise was the result of business reasoning, according to Art Glattke, SCRAMP’s director of public relations. “We had some notes from our fans last year that two classes (250cc and 500cc) weren’t enough of a show, that it wasn’t enough for the (admission) dollars charged,” he said. “So we decided to bring over the sidecars.”

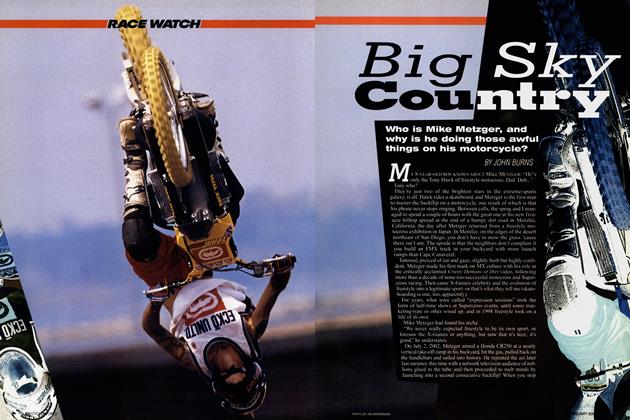

The sidecars—called “worms” because they’re long and slender and because they wiggle, sometimes violently, under acceleration and braking—are specialty machines which may or may not be motorcycles, but which clearly, once their smooth Kevlar bodywork is removed, display their close relationships to the twowheeled world.

Built by Louis Christen Racing in Switzerland, the chassis are of aluminum monocoque construction, the same used by the lower-level formula racing cars. The chassis is a sideways sort of affair, with the front wheel hung off the monocoque tub’s prow via a system of double parallelograms, with an inboard shock/spring unit operated by a pull rod as on Indy and FI cars. Steering is through a hub-center design that places the handlebar just inches above and slightly behind the 9-inch front slick. The rear wheel, with its 10-inch slick, is hung off the right side of the tub with upper and lower A-arms and pull-rod suspension, again standard formula-car practice. Suspension travel, front and rear, is about an inch and a half. The sidecar wheel, on most rigs placed on the left and upon which can be mounted either a 9or a 10-inch slick, is solidly mounted, with no travel at all, but is fully adjustable for camber, toe-in and ride height.

Chassis cost about $50,000 each complete with bodywork, according to van Dam, who says most teams havé just one chassis. The engines— which are inline, four-cylinder, 500cc two-stroke developments of the Yamaha TZ500—make about 150 horsepower and are hung from the right side of the monocoque, just behind the driver and just ahead of the rear wheel. The exhaust expansion chambers snake forward under the formed pan the driver kneels upon and emit from the bodywork on the right, just behind the front wheel, a high-decibel howl.

With TZ500 parts becoming rare, says van Dam, most engines now are developments of the Yamaha unit built by Krauser Engineering of West Germany. These sell for about $25,000 a copy, and each team brings three or four to each race.

Setting up a sidecar chassis is really a matter of arriving at the correct > choice of tires: Too hard a compound means no grip, too soft a compound means tread surface blisters. Both Avon and Yokohama offer sidecar tires based on their Formula 3 racecar designs, but which use slighly altered compounds and constructions. Tire pressure, width, compound and sidewall stiffness can be different for each of the sidecar’s three wheels; this mind-numbing number of variables means that as well as sorting gearing and carburetion for each circuit they visit, sidecar teams also spend considerable time sorting out rubber. According to Lucky Strike driver Egbert Streuer, “You need a bit of luck. It’s not easy.”

The key to a fast lap, according to ’87 and ’88 world champion Steve Webster, is getting the proper rubber on the chair. If the hack tire’s compound is too soft, the tire will dig into the pavement on fast right-handers, levering the outfit’s drive wheel off the pavement. But if the compound is just right, the driver can drift the rig through right-hand corners and turn lap times that, on some circuits, are very close to those of the GP bikes.

But what about left-hand turns? “They turn left absolutely brilliantly,” allows driver Tony Baker, who, with passenger Trevor Hopkinson, could manage no better than 13th at Laguna Seca. But getting them to handle brilliantly is as much the responsibility of the passenger as it is of the driver (see “White knuckles on a wild worm,” pg. 65 ), for the passenger is movable ballast. On lefthanders, he hangs his butt so far off the chair that many passengers have roadracing knee pads sewn to the left cheek of their racing suits, giving new urgency to the term “bottoming out.” On right-handers and straightaways, the passenger shifts his weight to the top of the drive wheel.

The spice to all this is that for all their impressive speed and maneuverability, the sidecars remain basi-

cally unstable, especially under heavy braking, when their light, sensitive steering is easily deflected by ripples and ridges on the racing surface. Thus, the rigs dart, dive, drift and lift their chair wheels under hard cornering despite the passenger’s high-energy scrambling. The payoff for spectators is an incredible show, which is why sidecar racing is very popular in Europe. The payoff is not bad for the teams, either, so long as they finish in the top five. If they can manage that, said van Dam, they can get rich. If not, they’ll continue as hobbyists.

The economics of world championship sidecar racing are such that this year, a front-line effort costs about $600,000, though next year the ante will be raised to about $750,000.

“This is small money for a big potential—a world championship,” insists van Dam, who says sidecars are very much less-expensive to race than 250cc and 500cc GP bikes. He claims this is because the motorcycle manufacturers, who charge considerable sums for engines and other racing components, have been uninterested in the sport.

That, however, appears to be changing; according to van Dam, two > Japanese motorcycle manufacturers (who he declined to name) have expressed interest in the sport’s 1990 season. For that and other reasons, van Dam believes, 1990 will be the breakthrough year for the world sidecar championship, when for the first time, the outfits will race everywhere the 500cc GP bikes co mpete.

This year, the rigs will run just nine events, of which the USGP was first. So what will happen next year remains to be seen. Will the worms return? Will they have full factory teams, with factory engines, factory drivers and factory budgets? And if they do, will the expense of remaining competitive push the sport beyond the reach of the smaller operators who have supported the sport since its inception in 1949?

Nobody knows. What we do know is that the worms put on a wonderful show. Are they motorcycles? We’re not sure. But they’re steered by handlebars, shifted by foot, clutched by hand, go like crazy and are great fun to watch.

That’s enough for us. g]