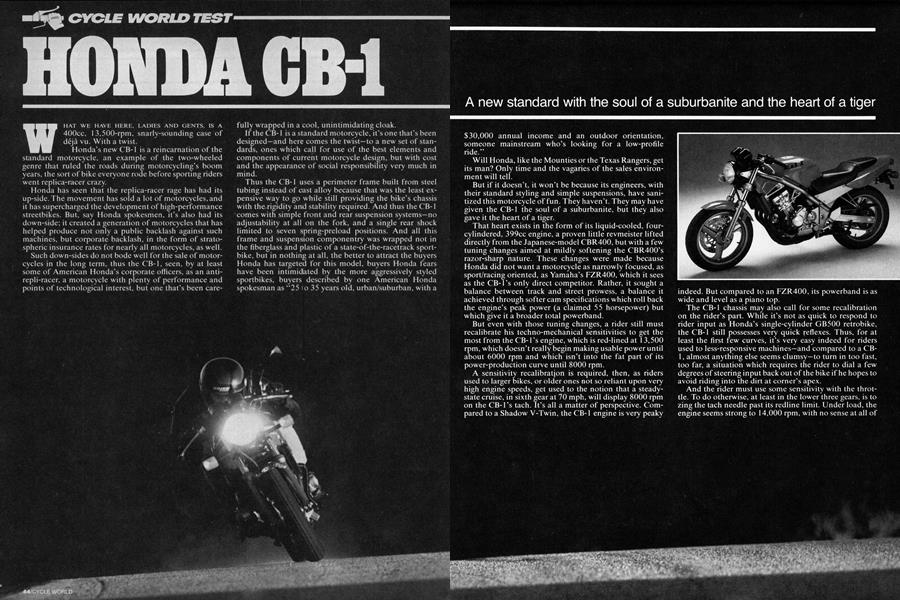

HONDA CB-1

CYCLE WORLD TEST

WHAT WE HAVE HERE, LADIES AND GENTS, IS A 400cc, 13,500-rpm, snarly-sounding case of déjà vu. With a twist. Honda’s new CB-1 is a reincarnation of the standard motorcycle, an example of the two-wheeled genre that ruled the roads during motorcycling’s boom years, the sort of bike everyone rode before sporting riders went replica-racer crazy.

Honda has seen that the replica-racer rage has had its up-side. The movement has sold a lot of motorcycles, and it has supercharged the development of high-performance streetbikes. But, say Honda spokesmen, it’s also had its down-side; it created a generation of motorcycles that has helped produce not only a public backlash against such machines, but corporate backlash, in the form of stratospheric insurance rates for nearly all motorcycles, as well.

Such down-sides do not bode well for the sale of motorcycles in the long term, thus the CB-1, seen, by at least some of American Honda’s corporate officers, as an antirepli-racer, a motorcycle with plenty of performance and points of technological interest, but one that’s been carefully wrapped in a cool, unintimidating cloak.

If the CB-1 is a standard motorcycle, it’s one that’s been designed—and here comes the twist—to a new set of standards, ones which call for use of the best elements and components of current motorcycle design, but with cost and the appearance of social responsibility very much in mind.

Thus the CB-1 uses a perimeter frame built from steel tubing instead of cast alloy because that was the least expensive way to go while still providing the bike’s chassis with the rigidity and stability required. And thus the CB-1 comes with simple front and rear suspension systems—no adjustability at all on the fork, and a single rear shock limited to seven spring-preload positions. And all this frame and suspension componentry was wrapped not in the fiberglass and plastic of a state-of-the-racetrack sportbike, but in nothing at all, the better to attract the buyers Honda has targeted for this model, buyers Honda fears have been intimidated by the more aggressively styled sportbikes, buyers described by one American Honda spokesman as “25 10 35 years old, urban/suburban, with a $30,000 annual income and an outdoor orientation, someone mainstream who’s looking for a low-profile ride.”

A new standard with the soul of a suburbanite and the heart of a tiger

Will Honda, like the Mounties or the Texas Rangers, get its man? Only time and the vagaries of the sales environment will tell.

But if it doesn’t, it won’t be because its engineers, with their standard styling and simple suspensions, have sanitized this motorcycle of fun. They haven’t. They may have given the CB-1 the soul of a suburbanite, but they also gave it the heart of a tiger.

That heart exists in the form of its liquid-cooled, fourcylindered, 399cc engine, a proven little revmeister lifted directly from the Japanese-model CBR400, but with a few tuning changes aimed at mildly softening the CBR400’s razor-sharp nature. These changes were made because Honda did not want a motorcycle as narrowly focused, as sport/racing oriented, as Yamaha’s FZR400, which it sees as the CB-l’s only direct competitor. Rather, it sought a balance between track and street prowess, a balance it achieved through softer cam specifications which roll back the engine’s peak power (a claimed 55 horsepower) but which give it a broader total powerband.

But even with those tuning changes, a rider still must recalibrate his techno-mechanical sensitivities to get the most from the CB-l’s engine, which is red-lined at 13,500 rpm, which doesn’t really begin making usable power until about 6000 rpm and which isn’t into the fat part of its power-production curve until 8000 rpm.

A sensitivity recalibratjon is required, then, as riders used to larger bikes, or older ones not so reliant upon very high engine speeds, get used to the notion that a steadystate cruise, in sixth gear at 70 mph, will display 8000 rpm on the CB-l’s tach. It’s all a matter of perspective. Compared to a Shadow V-Twin, the CB-1 engine is very peaky indeed. But compared to an FZR400, its powerband is as wide and level as a piano top.

The CB-1 chassis may also call for some recalibration on the rider’s part. While it’s not as quick to respond to rider input as Honda’s single-cylinder GB500 retrobike, the CB-1 still possesses very quick reflexes. Thus, for at least the first few curves, it’s very easy indeed for riders used to less-responsive machines—and compared to a CB1, almost anything else seems clumsy—to turn in too fast, too far, a situation which requires the rider to dial a few degrees of steering input back out of the bike if he hopes to avoid riding into the dirt at corner’s apex.

And the rider must use some sensitivity with the throttle. To do otherwise, at least in the lower three gears, is to zing the tach needle past its redline limit. Under load, the engine seems strong to 14,000 rpm, with no sense at all of running short of breath at those high speeds. But why tempt fate? This thing has 16 valves; to float them could be an expensive proposition.

If sensitivity is required when cranking the throttles open, it’s also required when slamming them closed. Because of the quick-spinning engine’s lack of flywheel weight, closed throttles result in immediate deceleration; allowing them to slam shut on the entrance to a corner can result in more deceleration than was intended. The thing to do is concentrate on smoothness; think your way through a series of curves, instead of powering your way through, and you’ll be rewarded with lean angles prodigious enough to change your perspective on where the horizon is supposed to be. Think your way through upshifts, keeping the engine in the lusty segment of its power curve, and you’ll be rewarded not only with vigorous acceleration but with an aural delight as the exhaust shrieks its exit through a beautiful 4-into-l extraction system that looks more like a refugee from a race shop than a production item.

Though the CB-1 is intended for wide appeal, it isn’t for everyone. It’s small, with a 53.9-inch wheelbase and 30.5-inch seat height; so lankier riders aren’t likely to remain comfortable over longer rides. And its seat is narrow and thinly padded, guaranteeing that the rider will bless the engineer who insured that the bike would require its reserve fuel supply after about 120 miles. Any passenger also will bless the bike’s short cruising range, as rear-seat accommodations make even fewer concessions to comfort than do those of the rider.

But enough carping. We like the CB-l, like it for its chassis, which changes line easily and which serves to broaden corners, and for its quick, easy-revving engine, which serves to shorten straights. And we like that Honda remembered to add important pieces like a centerstand and a neat little tool kit.

Honda would seem to be banking on marketplace acceptance of this bike; company representatives say 5000 to 6000 of them will be brought here this year to sell for approximately $4500, with the final price not set by the time of our deadline.

Now, five or six thousand units of anything isn’t going to make or break American Honda, but think of the name of this cool-blue, unintimidating motorcycle: CB-l. If a zero represents null, a void, then l represents—well, something, the opposite of nothing, the first. This bike, then, might be seen as evidence of a rethink by Honda of motorcycles and motorcycling. Its color isn’t a calm, intellectual blue by accident. Honda sees the CB-l as the thinking man’s motorcycle, a bike with which to capture someone who wants an all-around motorcycle, not a narrowly focused look-at-me replica racer. This is Honda’s anti-replica, and we like it a lot.

HONDA CB-1

SPECIFICATIONS

American Honda Motor Co., Inc.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

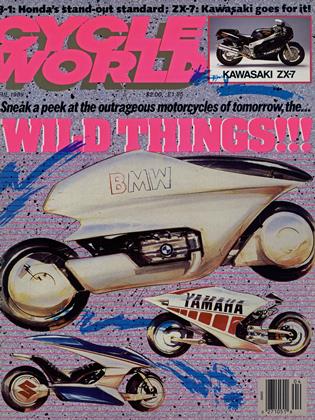

Up Front

Up FrontSo Many Curves, So Little Time

April 1989 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeSilver Wing For A Silver Eagle

April 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsTen Percenters

April 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's Spada: the Newest World Standard

April 1989 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupHailwood Ducati For Sale: $19,000

April 1989