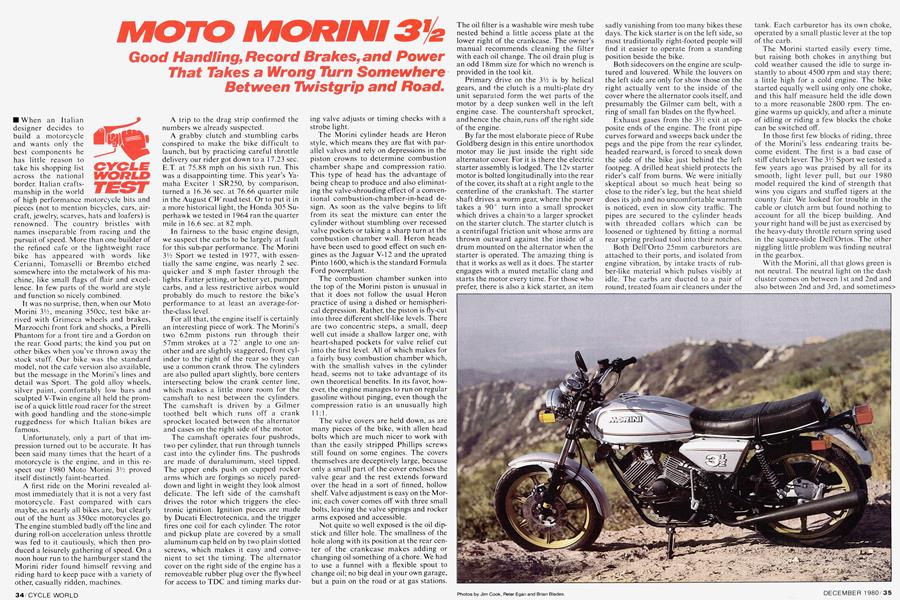

MOTO MORINI 3 1/2

CYCLE WORLD TEST

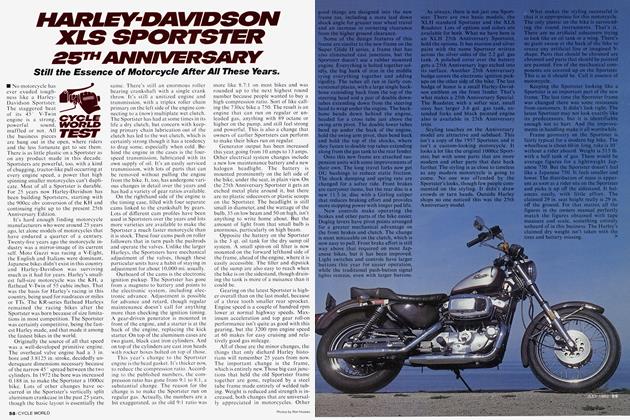

Good Handling,Record Brakes,and Power That Takes a Wrong Turn Somewhere Between Twistgrip and Road.

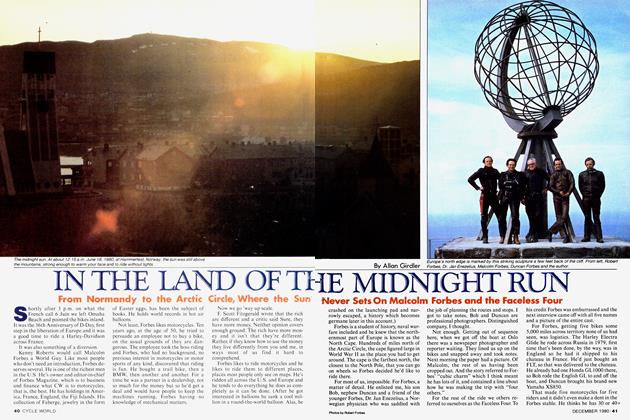

When an Italian designer decides to build a motorcycle and wants only the best components he has little reason to take his shopping list across the national border. Italian craftsmanship in the world of high performance motorcycle bits and pieces (not to mention bicycles, cars, aircraft, jewelry, scarves, hats and loafers) is renowned. The country bristles with names inseparable from racing and the pursuit of speed. More than one builder of the refined cafe or the lightweight race bike has appeared with words like Cerianni, Tomaselli or Brembo etched somewhere into the metalwork of his machine, like small flags of flair and excellence. In few parts of the world are style and function so nicely combined.

It was no surprise, then, when our Moto Morini 3*/2, meaning 350cc, test bike arrived with Grimeca wheels and brakes, Marzocchi front fork and shocks, a Pirelli Phantom for a front tire and a Gordon on the rear. Good parts; the kind you put on other bikes when you’ve thrown away the stock stuff. Our bike was the standard model, not the cafe version also available, but the message in the Morini’s lines and detail was Sport. The gold alloy wheels, silver paint, comfortably low bars and sculpted V-Twin engine all held the promise of a quick little road racer for the street with good handling and the stone-simple ruggedness for which Italian bikes are famous.

Unfortunately, only a part of that impression turned out to be accurate. It has been said many times that the heart of a motorcycle is the engine, and in this respect our 1980 Moto Morini 3'/2 proved itself distinctly faint-hearted.

A first ride on the Morini revealed almost immediately that it is not a very fast motorcycle. Fast compared with cars maybe, as nearly all bikes are, but clearly out of the hunt as 350cc motorcycles go. The engine stumbled badly off the line and during roll-on acceleration unless throttle was fed to it cautiously, which then produced a leisurely gathering of speed. On a noon hour run to the hamburger stand the Morini rider found himself revving and riding hard to keep pace with a variety of other, casually ridden, machines.

A trip to the drag strip confirmed the numbers we already suspected.

A grabby clutch and stumbling carbs conspired to make the bike difficult to launch, but by practicing careful throttle delivery our rider got down to a 17.23 sec. E.T. at 75.88 mph on his sixth run. This was a disappointing time. This year’s Yamaha Exciter 1 SR250, by comparison, turned a 16.36 sec. at 76.66 quarter mile in the August C'W road test. Or to put it in a more historical light, the Honda 305 Superhawk we tested in 1964 ran the quarter mile in 16.6 sec. at 82 mph.

In fairness to the basic engine design, we suspect the carbs to be largely at fault for this sub-par performance. The Morini 3'/2 Sport we tested in 1977, with essentially the same engine, was nearly 2 sec. quicker and 8 mph faster through the lights. Fatter jetting, or better yet, pumper carbs, and a less restrictive airbox would probably do much to restore the bike’s performance to at least an average-forthe-class level.

For all that, the engine itself is certainly an interesting piece of work. The Morini’s two 62mm pistons run through their 57mm strokes at a 72° angle to one another and are slightly staggered, front cylinder to the right of the rear so they can use a common crank throw. The cylinders are also pulled apart slightly, bore centers intersecting below the crank center line, which makes a little more room for the camshaft to nest between the cylinders. The camshaft is driven by a Gilmer toothed belt which runs off a crank sprocket located between the alternator and cases on the right side of the motor.

The camshaft operates four pushrods, two per cylinder, that run through tunnels cast into the cylinder fins. The pushrods are made of duraluminum, steel tipped. The upper ends push on cupped rocker arms which are forgings so nicely pareddown and light in weight they look almost delicate. The left side of the camshaft drives the rotor which triggers the electronic ignition. Ignition pieces are made by Ducati Electrotécnica, and the trigger fires one coil for each cylinder. The rotor and pickup plate are covered by a small aluminum cap held on by two plain slotted screws, which makes it easy and convenient to set the timing. The alternator cover on the right side of the engine has a removeable rubber plug over the flywheel for access to TDC and timing marks during valve adjusts or timing checks with a strobe light.

The Morini cylinder heads are Heron style, which means they are flat with parallel valves and rely on depressions in the piston crowns to determine combustion chamber shape and compression ratio. This type of head has the advantage of being cheap to produce and also eliminating the valve-shrouding effect of a conventional combustion-charnber-in-head design. As soon as the valve begins to lift from its seat the mixture can enter the cylinder without stumbling over recessed valve pockets or taking a sharp turn at the combustion chamber wall. Heron heads have been used to good effect on such engines as the Jaguar V-12 and the uprated Pinto 1600, which is the standard Formula Ford powerplant.

The combustion chamber sunken into the top of the Morini piston is unusual in that it does not follow the usual Heron practice of using a dished or hemispherical depression. Rather, the piston is fly-cut into three different shelf-like levels. There are two concentric steps, a small, deep well cut inside a shallow larger one, with heart-shaped pockets for valve relief cut into the first level. All of which makes for a fairly busy combustion chamber which, with the smallish valves in the cylinder head, seems not to take advantage of its own theoretical benefits. In its favor, however, the engine manages to run on regular gasoline without pinging, even though the compression ratio is an unusually high 11:1.

The valve covers are held down, as are many pieces of the bike, with alien head bolts which are much nicer to work with than the easily stripped Phillips screws still found on some engines. The covers themselves are deceptively large, because only a small part of the cover encloses the valve gear and the rest extends forward over the head in a sort of finned, hollow shelf. Valve adjustment is easy on the Morini; each cover comes off with three small bolts, leaving the valve springs and rocker arms exposed and accessible.

Not quite so well exposed is the oil dipstick and filler hole. The smallness of the hole along with its position at the rear center of the crankcase makes adding or changing oil something of a chore. We had to use a funnel with a flexible spout to change oil; no big deal in your own garage, but a pain on the road or at gas stations. The oil filter is a washable wire mesh tube nested behind a little access plate at the lower right of the crankcase. The owner’s manual recommends cleaning the filter with each oil change. The oil drain plug is an odd 18mm size for which no wrench is provided in the tool kit.

Primary drive on the 3 V2 is by helical gears, and the clutch is a multi-plate dry unit separated form the wet parts of the motor by a deep sunken well in the left engine case. The countershaft sprocket, and hence the chain, runs off the right side of the engine.

By far the most elaborate piece of Rube Goldberg design in this entire unorthodox motor may lie just inside the right side alternator cover. For it is there the electric starter assembly is lodged. The 12v starter motor is bolted longitudinally into the rear of the cover, its shaft at a right angle to the centerline of the crankshaft. The starter shaft drives a worm gear, where the power takes a 90° turn into a small sprocket which drives a chain to a larger sprocket on the starter clutch. The starter clutch is a centrifugal friction unit whose arms are thrown outward against the inside of a drum mounted on the alternator when the starter is operated. The amazing thing is that it works as well as it does. The starter engages with a muted metallicclang and starts the motor every time. For those who prefer, there is also a kick starter, an item sadly vanishing from too many bikes these days. The kick starter is on the left side, so most traditionally right-footed people will find it easier to operate from a standing position beside the bike.

Both sidecovers on the engine are sculptured and louvered. While the louvers on the left side are only for show those on the right actually vent to the inside of the cover where the alternator cools itself, and presumably the Gilmer cam belt, with a ring of small fan blades on the flywheel.

Exhaust gases from the 3V2 exit at opposite ends of the engine. The front pipe curves forward and sweeps back under the pegs and the pipe from the rear cylinder, headed rearward, is forced to sneak down the side of the bike just behind the left footpeg. A drilled heat shield protects the rider’s calf from burns. We were initially skeptical about so much heat being so close to the rider’s leg, but the heat shield does its job and no uncomfortable warmth is noticed, even in slow city traffic. The pipes are secured to the cylinder heads with threaded collars which can be loosened or tightened by fitting a normal rear spring preload tool into their notches.

Both Dell’Orto 25mm carburetors are attached to their ports, and isolated from engine vibration, by intake tracts of rubber-like material which pulses visibly at idle. The carbs are ducted to a pair of round, treated foam air cleaners under the tank. Each carburetor has its own choke, operated by a small plastic lever at the top of the carb.

The Morini started easily every time, but raising both chokes in anything but cold weather caused the idle to surge instantly to about 4500 rpm and stay there; a little high for a cold engine. The bike started equally well using only one choke, and this half measure held the idle down to a more reasonable 2800 rpm. The engine warms up quickly, and after a minute of idling or riding a few blocks the choke can be switched off.

In those first few blocks of riding, three of the Morini’s less endearing traits become evident. The first is a bad case of stiff clutch lever. The 3 */2 Sport we tested a few years ago was praised by all for its smooth, light lever pull, but our 1980 model required the kind of strength that wins you cigars and stuffed tigers at the county fair. We looked for trouble in the cable or clutch arm but found nothing to account for all the bicep building. And your right hand will be just as exercised by the heavy-duty throttle return spring used in the square-slide Dell’Ortos. The other niggling little problem was finding neutral in the gearbox.

With the Morini, all that glows green is not neutral. The neutral light on the dash cluster comes on between 1st and 2nd and also between 2nd and 3rd, and sometimes> when it is between neither. So as you absent-mindedly downshift your way to a stoplight, you roll up believing yourself in neutral and kill the engine by releasing the clutch lever. Or the stoplight turns green and you shift into 1st, which is really 2nd, and find yourself stalled because the Morini has an off-idle flat spot that won’t tolerate 2nd gear starts.

It’s no big problem; bikes don’t really need neutral lights anyway. They’re just a convenience, and, to some, a distraction, but if you bother to install one on a motorcycle, it might as well work. It would also matter less if the Morini were easier to shift at a standstill, but it has one of those gearboxes that like you to get everything done while the bike is still rolling.

Except for this occasional dabbing around at stoplights, the gearbox shifts nicely, especially considering that much bellcrank-and-shaftwork was needed to move the lever to the left side for U.S. regulations. The ratios are well spaced and high gear is a delight to drop into simply because it feels high, rather than undergeared and hectic. Twins, of course, with their lower frequency engine vibrations, tend to promote that easy-cruising sensation.

What those vibrations lack in frequency, however, they sometimes make up in amplitude, and in the Morini’s case it feels as though they all congregate at the left handgrip. It vibrates and tingles badly at most road speeds. The right grip is damped somewhat by steady hand pressure on the throttle, but the other side will have you resting your numb left hand on the tank after only a short time on the road. Rubber isolation mounts on the handlebars might help, or even some thick foam grips.

Most riders found the seating position comfortable. The handlebars were a nice compromise between the high touring bars that have you slouched back like a parachute full of wind and the ultra low sport or clubman bars than can bring on an eventual cricking of the neck. The Moto Morini bars allow you to lean just far enough forward that the wind helps support your weight at road speeds, removing some of the strain from arms and back. As another nice touch, the footrests have crown-tooth brackets that interlock to allow position adjustment, much the way 305 Superhawk pegs did. It wouldn’t break our hearts to see adjustable footpegs on a few other motorcycles we can think of, or simply returned to motorcycling in general. The Morini seat, in the Italian sport bike tradition, is firm and fairly narrow. One hour is about maximum sitting time before you begin to look favorably upon other activities, like standing and walking.

Handling of the Moto Morini V/i is hard to fault. Excellent forks and shocks, relatively light weight, proper frame geometry and one of the best sets of street tires available all work toward the same end. With rake and trail at 29.5° and 4 in. and a wheelbase of 55.25 in. the bike has an uncommonly long and stable feel for a 350. It is light enough to be pitched into corners quickly and change direction through S-bends with little effort, yet the steering is slow enough that the Morini never feels twitchy or nervous. One rider said he thought the bike might even have a slight tendency to fall into turns, but not enough to be a problem. Damping is adequate at both ends and suspension compliance over bumpy stretches of road is firm without being harsh.

A cynic on the staff pointed out that there’s no real way to judge the handling of the 3'/2 compared with other 350-450cc bikes because it doesn’t have enough power to test the integrity of the frame or suspension; that nearly any low-output motorcycle can be made to handle well until you start pumping another 10 or 20 hp through the swing arm. Be that as it may, the Morini corners very well with what power it has.

The tires are superb. The Pirelli Gordon, mounted on the rear of the 3V6, has been gaining wide reputation of late as an excellent rear tire for box stock and production roadracers who like the back of a motorcycle to stay where it’s put in hard corners. The Phantom front, also a good choice, has enough sidewall and stick at high lean angles to balance the Gordon. If more new motorcycles left the showroom with tires of this quality we wouldn’t have to be so careful on the way home. On the other hand, new bikes would cost more and there wouldn’t be as many unused cycle tires available for tree swings and boat moorings.

Having good tires also did no harm to the Morini’s braking capabilities. Nor did the high quality caliper, disc, drum and friction material. The 3V2 stopped from 60 mph in just 115 ft. That distance rebreaks the 400 class record just broken by the Kawasaki Belt Drive 440 LTD, which hauled itself down in 129 ft. That’s 14 ft. shorter than the old record; a substantial distance, especially if that last 14 ft. happens to end on the other side of a truck turning left in your path. Added to their excellent stopping power, the Morini brakes have a solid, progressive feel; no fade or pulsing at the front and no chatter or sudden lockup at the rear. An allaround commendable set of stoppers.

Electrics on the Morini are straightforward and simply laid out, if a little unusual in some respects. Everything can be reached by removing the seat and sidecovers, which are held in place by bolts with nice big plastic finger knobs fused onto them, so tools are not needed to get to your tools, as is sometimes the case. A large battery, just under the seat, is also held down with finger knobs. The right sidecover conceals a terminal block that looks like Central Exchange before the age of computers. Dozens of wires bloom out of the harness and terminate at male/ female spade connectors along the top of the terminal block. It looks confused at first until you realize that everything is color coded and easily reached for repair or circuit testing.

The handlebar switches take a little getting used to, mainly because you have so many choices at the left grip. There are separate rockers for switching the headlight on and off (yea), high and low beam, turn signals, and a fourth rocker that honks the horn in one direction and flashes the headlight in the other. The headlight will flash only while switched to high beam. The on/off switch for the headlight also has a parking light position that turns on the tail light and, oddly, the instrument lights. One suspects economy rather than careful planning there. The right grip houses only a rocker kill switch and starter button.

The tach and speedometer are both Veglia instruments, tach on the left by traditional Italian practice. The faces are large and easy to read, though our speed trap testing showed the speedometer to read about 5 mph faster at an indicated 60 mph. The tachometer is electronic and gets its information from the ignition coil that fires the rear cylinder.

Another novel electronic feature is the fuel petcock, which is solenoid operated and switches open only when the ignition switch is turned on. There is a conventional lever operated petcock on the other side of the tank for reserve fuel. It may be that the electric petcock is draining off power that would normally go to the horn. Something is. The dismally weak horn may be the last thing you hear before fetching up against some vehicle that didn’t get out of your way because it couldn’t hear the horn.

Another daily irritant with the Morini is the sidestand. It is, in the BMW tradition, spring loaded and will snap upward immediately when unweighted. Don’t park the Morini even slightly downhill, jostle the bike, turn the front fork, etc. or the sidestand will row the bike forward like a small oar and cause it to founder. We played it safe, using only the centerstand.

Failures? Only one. The sprocket side chain adjuster split in two at the drag strip, allowing the right side of the axle to pivot forward, throwing the rear tire out of line. The hub and axle nuts were good and tight, and after the adjuster broke we moved the axle back into position and cranked it down really tight. On acceleration it slipped again. Apparently the adjuster carries a good part of the load in locating the axle. If that is the case, the piece needs to be stronger. Another small black eye is the tool kit, which has to be one of the worst tool sets ever banished to the underside of a motorcycle seat. The wrenches are too weak and too short to be of any use and are stamped out of thin sheet metal. (“Yes,” one observer noted, “they certainly look like pieces of sheet . . .”) Conversely, wrapped around the tool kit is one of the best owner’s manuals we’ve seen. It has large, clear pictures, good maintenance information, and it even tells you how to overhaul the bottom end and install pistons and rings.

continued on page 87

MOTO MORINI 3 1/2

$2600

continued from page 37

Our lingering collective feeling about the Moto Morini is that it’s a nice handling, well finished, basically sound motorcycle in search of a good engine. Not a prettier engine or a more interesting one, but an engine with the power and throttle response the bike deserves.

We recognize that not all motorcycles need to be high-performance pavement burners; that such traits as economy, longevity, simplicity, ease of maintenance, and even the right exhaust note are every bit as worthwhile as the ability to blast away from stoplights or run a fast quarter mile. Bikes that look and feel right and encourage the enthusiast to work on them have a place, whether or not they happen to be the quickest thing on the block. But we live in an era when most of those virtues can be found in bikes that also deliver spirited performance as a second side to their workaday characters. Even the humblest 250 Single street commuter is now expected to get out of its own way with some dispatch. And it does.

Bikes like the Moto Morini, of course, are not always bought on comparative statistics. People who spend $2600 for a 350 have more in mind than convenient commuting or running to the store. They spend that kind of money because they want something unusual, interesting, carefully finished and assembled from high quality components. And they want a machine with those small imperfections that separate the hand-made from the mass produced article. Such a bike says something about the owner that the average commuter bike does not. It says that he has chosen his motorcycle and not bought it by accident or because a fast-talking salesman had too many of them. That sort of bike says he is not a beginner.

With just a little more attention to detail, and perhaps a few changes in carburetion and tuning, the Moto Morini would deserve a place among that class of motorcycles.