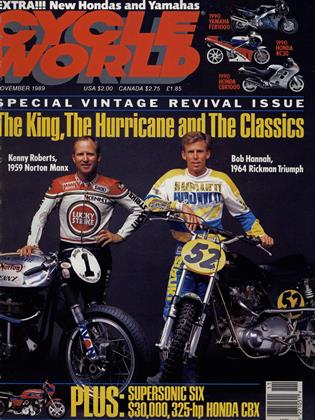

MANX MAGIC

Kenny Roberts takes on the Norton legend

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

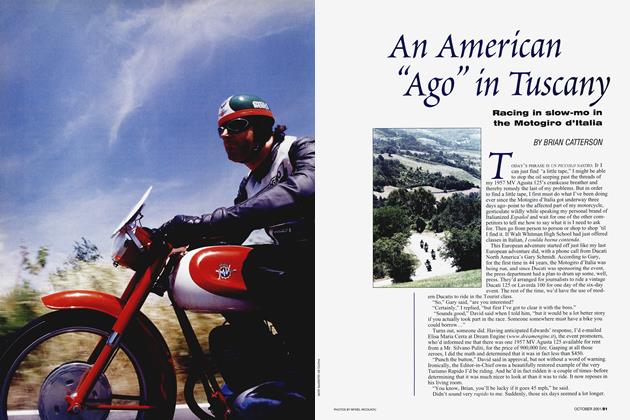

IT DIDN’T TAKE KEEN INSIGHT TO SEE THAT KENNY ROBerts did not want to be here. Just off a jetliner from Sweden, where his roadracing team’s lead rider, Wayne Rainey, had crashed and lost the lead in the grand prix series point chase, the three-time world champion slouched in the car with his arms crossed and muttered, “God, I dread riding this bike.” He hadn't even seen the legendary 1959 Norton Manx we had talked him into riding and already he hated it. I only hoped the boys back at the track had the Manx running by the time we arrived. If not, it was going to be a very tough morning.

Convincing Roberts to ride the bike was no easy matter. After all, as far as he is concerned, the only racebike worth riding is a 1 50-horsepower, 500cc GP missile. Still, cajoling him into swinging a leg over this most successful of all British roadracing Singles proved easier than actually finding a suitable Manx. Most of the problem stems from a production period from the late 1940s to 1961, during which Norton only produced about 1 30 Manxs a year, and today most of the restored versions are safely tucked away in museums and garages, accruing value. Men who own Manxs don’t usually ride them, much less race them; they have become too valuable, worth upwards of $25,000.

We knew Don Vesco, of land-speed-record fame, had been vintage racing one since 1983, but when we contacted him, he told us that the Manx had been loaned to him by Rob Iannucci, part owner of vintage-racing powerhouse Team Obsolete, and that the bike had just been sent back to the team’s headquarters in New York for a muchneeded refurbishment. A quick call to Iannucci had two mechanics working full-time on the Manx to rebuild it in time to be air-shipped back to California.

The 1959 Manx we pulled out of the crate may well be one of the best racing Manxs in existence, but it is far from a perfectly restored version of the machine as it was raced in the late Fifties and early Sixties. It is not a concours bike, and in many ways, not even pretty. Iannucci is noted for pushing vintage-racing rules to their limits, and some sticklers in the classic-bike world object that he has fitted the bike, and many of the other racers in Team Obsolete’s stable, with so many new-and-improved parts that the machines are actually modern racebikes that resemble classic bikes. In defense, Iannucci claims that he does nothing to

his bikes that could not have been done in the old days. “We’re not talking quantum leaps in technology here,” he says. “As long as it looks okay from the outside, and we don’t go ‘over the top' with technology, it’s all right.”

Just how Iannucci got ahold of this particular Manx is a small story in itself, because he claims that the bike was owned and raced by none other than Mike “The Bike” Hailwood when he made his racing tour of the U.S. in 196 1 and 1962. Iannucci says that a Syd Mularney bought the bike from the Hailwood stable, then sold it to Adrian Richmond, who ended up in Canada. Iannucci tells the rest of the story: “Richmond and his wife considered this bike ‘family.’ They would take it to the races, then bring it home, work on it and put it in the living room. They loved it. But Mrs. Richmond died in 1980, and when Richmond remarried, his new wife never appreciated the machine, so it was put up for sale. Richmond literally cried when he sold the bike to me—I even offered to give it back—but he had no choice and he had to part with it.”

Basically, Iannucci’s bike is a 1 959 Manx M30 featuring the heralded Featherbed frame, designed by Irish brothers Rex and Cromie McCandless, a revolution in handling when it was introduced on the 1950 factory Manx racers. The 499cc engine has been updated to 1961 specifications, including a higher compression ratio, a different cam profile and a reshaped piston dome. In addition, the bike has a double-leading-shoe front brake from 1961.

Just after Iannucci took possession of this Manx in 1982, it was crashed heavily, destroying most of the components and bending the frame, though team rider Dave Roper escaped relatively unscathed. “It was the most-destructive crash I have ever witnessed,” says Iannucci. He had to completely rebuild the bike, and figured that was an appropriate time to make some needed upgrades. He replaced the standard four-speed gearbox with a Britishbuilt Quaife six-speed unit built to Team Obsolete specs. In place of the stock 19-inch wheel rims—increasingly difficult to get racing tires for—he used the widest 18-inch rims allowed and replaced the round-tube swingarm with a works, oval-section one to make room for the wider rear tire. Also, Iannucci raised the footpegs and had a highmounted exhaust pipe built to preclude cornering-clearance problems.

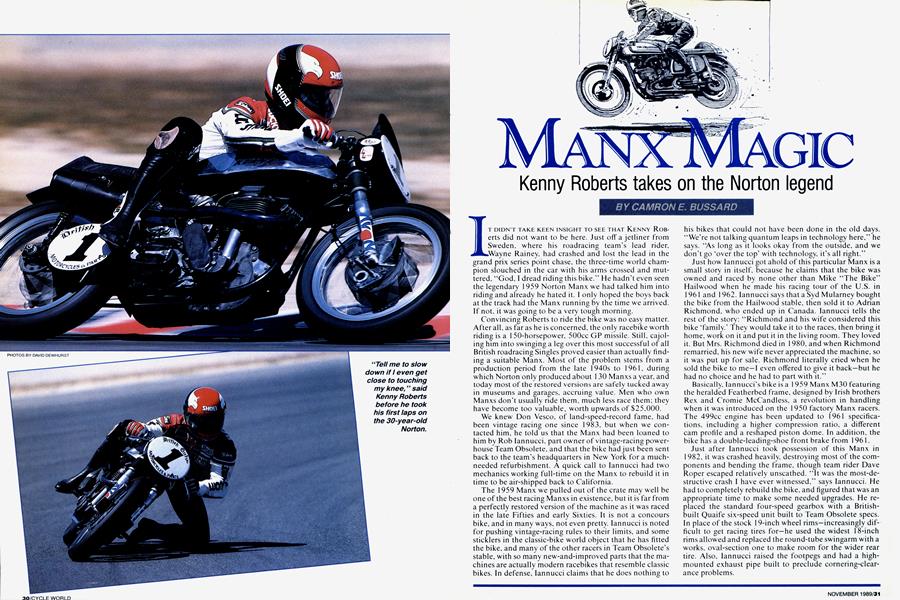

So modified and freshly rebuilt, this is the machine that greeted a reluctant Kenny Roberts, it’s shinybut-scratched alloy fuel tank, its blued-from-heat header pipe and its just-scuffed-in tires signaling an eagerness to get underway. Roberts' interest in the bike picked up the moment he got a look at it. “I’ve seen one of these before,” he said. “It was in Germany, at Hockenheim. We would run up there to see the vintage races during the GP season.” Still, he was apprehensive as he pulled on his leathers and got ready for a couple of familiarization laps. After a short push—the only way to start a Manx— Roberts sat there revving the engine to keep it from expiring, a steady idle not being one of the things Manx Norton tuners apparently sullied themselves with. But as Roberts jockeyed the throttle, it was evident from the smile beneath his helmet he didn’t hate the bike as much as he wanted to.

Just before taking off, he joked, “If I get going fast enough to drag my knee, come out and make me stop.” Then he revved the bike to about six grand and blasted away, the deep, throaty blare of the Manx reverberating off the surrounding hills, sounding magnificently out of place on the newly repaved Laguna Seca racetrack, host to the latest in GP technology during the running of the U.S. Grand Prix a few months earlier. After some subdued laps, during a pause for still photos, Roberts admitted, “It isn’t as bad as I thought it would be. It has a hell of a lot of flywheel and real positive braking.”

A few more laps and Roberts was getting the hang of riding the 30year-old relic: “You have to keep the tach above 6000 rpm when you shift or the engine loses its momentum. It doesn’t accelerate very hard—there’s plenty of time to watch the tachometer.” As with a lot of the old fourstroke Singles, the Manx suffered from “megaphonitis,” a condition where the power flattens out to almost nothing in the mid-range. Drop the revs much below 5500 rpm and the Manx gets a terminal case of the bogs. With a redline of 7200 rpm, the Manx’s 1700-rpm powerband is narrower than some pipey two-strokes.

Toward the end of the session, Roberts picked up the pace, actually dragging his knee skids through some corners, his 1980s hang-off riding style looking more than a little out of place on the Manx. Roberts would charge hard into the turns, grab as much brake as he could, then slam the bike into the corner, whereas the riders in the Fifties and Sixties stayed pretty much planted in the seat and eased through the corners on “the line,” using their toes for feelers. But beyond a doubt, the King looked great on the bike, and you could easily imagine him giving Mike Hailwood or Geoff Duke one hell of a battle had they ever met on Manxs.

“This is like riding a 250cc GP bike,” said Roberts after pulling into the pits. “It's sensitive to the proper line through a corner in that you don’t have a lot of horsepower to play with, so to do fast laps you have to be right on the fast line all the time.” He praised the Manx’s handling and was surprised at how stable it was, saying, “This bike just doesn’t wobble,” a testament to the Featherbed frame.

That frame design was ahead of its time in 1950, and its influence has been far-reaching. Basically, the frame consists of a pair of tubes reaching down from the steering head, under the engine, back and around the transmission then back up to the steering head, sort of a narrower version of today’s backboneless, perimeter-style frames. It was a simple and elegant design that provided the best-handling chassis of its day. Consider that in 1961, the last year Norton produced the Manx, Mike Hailwood won the arduous Isle of Man TT on one, logging the first over-100-mph lap for a single-cylinder, race-finishing bike.

Twenty-eight years later, Roberts touched on one of the biggest differences between racing in the Fifties and in the Eighties. “With these old bikes, you don't have to worry about high technology, carbon fiber or computers,” he said. “You just tighten the axle and go.” While no one who has ever raced a Manx—a notoriously delicate machine when pushed to its performance limits— would agree wholeheartedly with that, the Manx does indeed harken back to a simpler time and more-naive racing environment.

While Roberts never came right out and said that he had a great time on the Norton, he did come away with an unexpected regard for the bike and for vintage racing. “I can see myself in 10 years or so having a ball with these kind of bikes,” he said before the competitor in him took over. “But I can see all sorts of ways to make it better. With better brakes and more power you could have a lot more fun,” he said with a smile.

Well, if Roberts wants to have more fun, he had better find a Manx pretty quickly. By the time he gets around to vintage racing, they may all be tucked away. But he did hint at something that should make historic racers take note. “I always wanted to ride one of those Güera 500 Saturnos. They were neat bikes,” he said of the beautiful Italian Singles of the l 950s. So watch out, and try not to be concerned if 10 years from now, you get passed on the outside by a kneedragging, tire-sliding old man on a scarlet-red Saturno. You’ll know then that Roberts couldn't locate a Manx.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

November 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

November 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

November 1989 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsLetters

November 1989 -

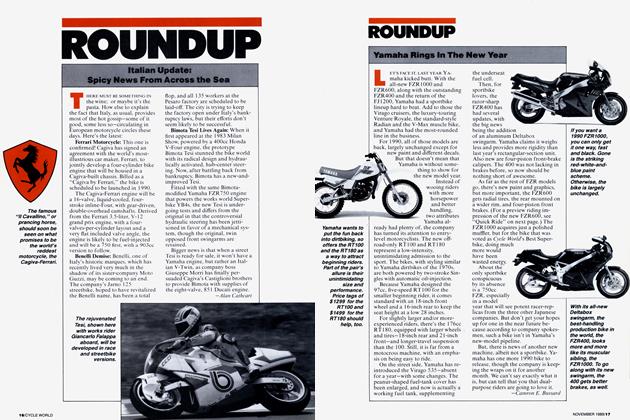

Roundup

RoundupItalian Update: Spicy News From Across the Sea

November 1989 By Alan Cathcart -

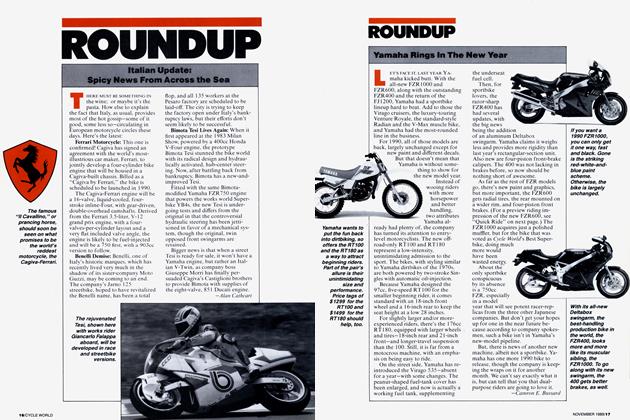

Roundup

RoundupYamaha Rings In the New Year

November 1989 By Camron E. Bussard