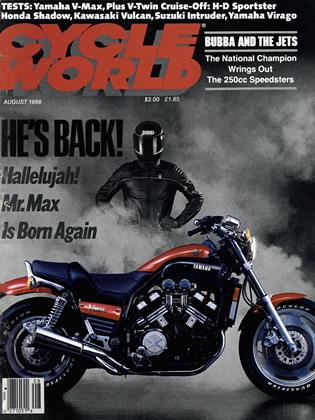

MAD MAX

One man builds his ultimate motorcycle

STEVE ANDERSON

PAUL CIVITELLO RUNS AN automobile restoration business in Waterbury, Connecticut, in the three-car garage behind his house. It's the kind of place you might take, say, a collection of parts that once made a 1932 Duesenberg. and a very fat check book. Return a year (maybe two) later, and your Duesenberg would be waiting, perfect, gleaming, better than new. And your checkbook would be anorexic.

For all his work on cars, though, Civitello is really a motorcycle guy at heart. He started riding at age 1 5 on a BSA Gold Star, and later, throughout the Sixties and Seventies, he was an enthusiastic Harley-Davidson dragracer. For 14 years he raced a Sportster, culminating with the A-modified record that had stood for eight years before he broke it with his 77incher on July 23, 1972.

But Civitello’s enthusiasm waned as his Harley had to be pushed to its mechanical limits and beyond to stay competitive. Finally, a year after setting the record, he saw it fall to a Honda CB750 with a hop-up kit. That was the last straw for Civitello. “I gave up; I just stopped racing,” he says.

But he didn’t give up motorcycling, and continued to read the magazines. In 1985, he saw the first test of the Yamaha V-Max in the pages of Cycle World, including our account of drag-testing that original Max with a 15-inch slick and wheelie bar. Motorcycle lust struck; says Civitello, “I couldn’t see myself on a Japanese motorcycle, but the V-Max . .

One thing led to another, and Civitello soon owned a V-Max and was running it at the local drag strip with, yes, a 15-inch rear slick. But naturally, a man with his skill and background couldn’t leave even a VMax alone. ‘T didn’t like the driveshaft—it just didn’t belong,” he says. So, the first part of his project was underway.

“I took the engine apart blind, with no investigation,” he recalls. Fortunately, what he found was encouraging. The gearbox output shaft rotated in the proper direction for chain drive (contrary to some misinformation in our Service column a year or so ago), and the driveshaft hardware could be fairly easily removed. Civitello welded a flange on the output shaft so a sprocket could be bolted on, and then altered the frame to clear a chain. “I had to move the upper frame cross member up an inch and a half, and I just made a little jog in the lower one."

That was just the beginning, though; he also had to make a swingarm. mount the Performance Machine 18-inch rear wheel and brakes, and make a new gas tank that wasn't in the chain's way. Civitello is sure it was worth the work, and estimates that removing the driveshaft and standard wheel cut weight by 60 pounds or more.

But the chain conversion wasn’t without its problems—specifically with the oil seal on the gearbox output shaft. The shaft-drive arrangement didn’t need a seal on the shaft (because the right-angle gear housing bolted over it) but the chain-drive conversion did. Civitello’s first solution was simply to use sealed bearings, but that was a near-disaster. “I wasjust going through the lights after a 10.20 pass, and the seals on the bearings let go and blew four quarts of oil out, over the rear tire and the track and everything. I can only thank God that I stayed upright, but the people at the track were ready to kill me for oiling the lane."

Civitello retreated to his shop and re-engineered his conversion with a proper oil seal; he's had no problems with oil-control since.

But his project was hardly finished. “I looked at the individual pieces on the motorcycle, and made each as light as possible: the footpegs, the seat, everything," explains Civitello. He designed a new exhaust system, as well. “I wanted to use the standard Yamaha header diameters—I figured they knew' more about exhaust systems than 1 did—and make all four of them equal length. It took me four attempts, and the pipe on the bike is welded together from more than 30 individual pieces.’’ Between the lightened parts, the chain-drive conversion and the new exhaust. Civitello’s V-Max has lost 125 pounds, and now weighs in at a feathery-light 475 pounds without gas.

Another chassis modification was simply insurance. “With the stock 29-degree steering-head angle, the bike handled prettv good." Civitello recollects, “but I went down on a Sportster once, from a wobble at 1 15 mph. So I pushed the head angle on the V-Max out to 36 degrees. I’m going about 135 mph at the end of the quarter, and the Max is so smooth you could ride hands-off."

With all the chassis work, Civitello has suprisingly left the engine alone. “It’s stock inside,” he says, “though people find that hard to believe when they hear it run. At the drag strip, it’s like you're racing a car against a motorcycle. It’s so loud it just drowns out any other bike." With stock internals, Civitello’s V-Max has powered him through the lights at 10.04 seconds and more than 135 mph. and only traction problems have kept it out of the nines.

“It used to relight the tire in third gear and smoke it the rest of the way down the strip," he says. “That’s when the track announcer started calling it Mad Max; I didn't give it that name. With the smoke and the noise, it’s such a crowd-pleaser."

It has also pleased Civitello, though its power has created a few problems. “Early on, it would bend rear axles. After I’d do a burnout and pass, I couldn't get the rear axle out. The first ones I made from normal steel, then I tried some high-strength stainless, and that bent, as well. Finally, I made an axle of some special titanium a friend of mine got for me, and so far it has held up.”

Mad Max also occasionally pops out of fourth gear, no matter how carefully Civitello sets up its gearbox. It’s a rare occurrence, but it needs only happen once to eliminate him at a meet. Currently, he has addressed the problem by gearing his bike to run third gear through the quarter. Think about that for a second: This V-Max is so strong that it can run low-10-second quarters with what effectively is a three-speed gearbox. Civitello hopes a new, more-advanced air-shifter will let him gear the bike to pull fourth, and drop him into the nines.

The final problem has been two exploded engines, both with broken connecting rods. Civitello is reluctant to blame any of this on the VMax. “I run hundreds of passes in a year, and launch the bike at 9000 rpm. Something has got to give eventually." He suggests that the engine failures may have resulted from overrevving, particularly in first gear, and as usual he has an answer: “I’ve been intending to make some connecting rods out of titanium. But don’t get me wrong. That motor is light-years ahead of anything else."

Obviously, then, this is a perfect matchup: a very special machine, and a very special man. Civitello is as much an artist as any sculptor, except his medium is steel, aluminum, chrome and paint, carved and molded and formed into cars and bikes. “My dream isn't money or fame," he says. “My dream in life is to produce the world’s ultimate Duesenberg."

In light of that fantasy, perhaps Civitello’s own assessment of his Mad Max says it all: “I was a die-hard Harley-Davidson man. I never could see myself on a Japanese bike. But if you said right now, ‘Here’s an unlimited amount of funds and a Sportster,’ well ... I wouldn't give up my Max." ÉE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue