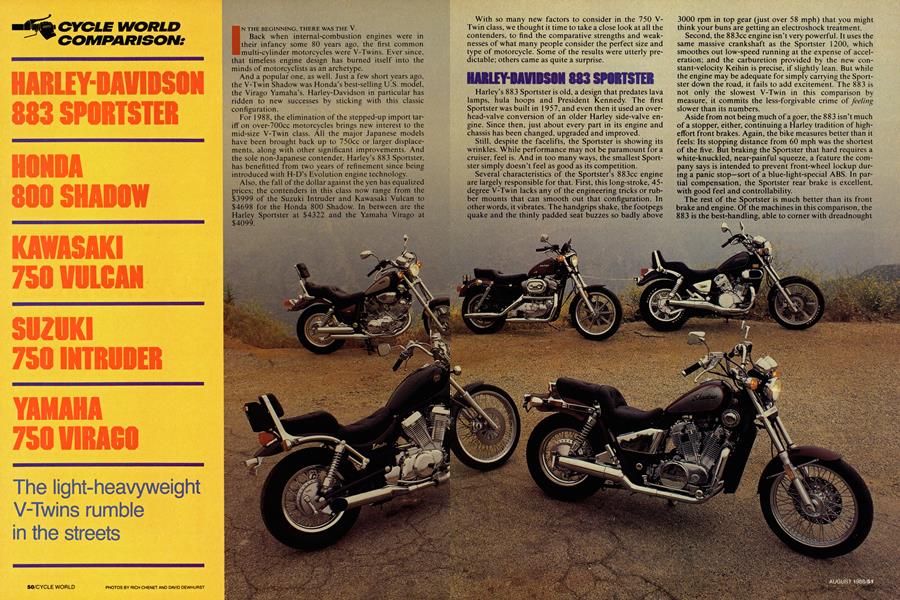

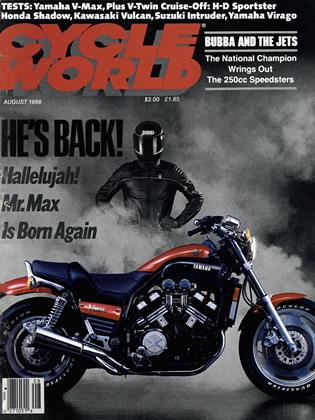

Harley-Davidson 883 Sporister Honda 800 Shadow Kawasaki 750 Vulcan Suzuki 750 Intruder Yamaha 750 Virago

August 1 1988Harley-Davidson 883 Sporister Honda 800 Shadow Kawasaki 750 Vulcan Suzuki 750 Intruder Yamaha 750 Virago August 1 1988

HARLEY-DAVIDSON 883 SPORISTER HONDA 800 SHADOW KAWASAKI 750 VULCAN SUZUKI 750 INTRUDER YAMAHA 750 VIRAGO

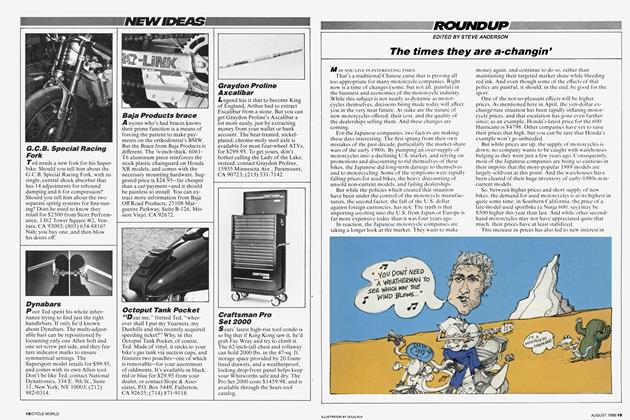

CYCLE WORLD COMPARISON:

The light-heavyweight V-Twins rumble in the streets

IN THE BEGINNING, THERE WAS THE V. Back when internal-combustion engines were in their infancy some 80 years ago, the first common multi-cylinder motorcycles were V-Twins. Ever since, that timeless engine design has burned itself into the minds of motorcyclists as an archetype.

And a popular one, as well. Just a few short years ago, the V-Twin Shadow was Honda’s best-selling U.S. model, the Virago Yamaha’s. Harley-Davidson in particular has ridden to new successes by sticking with this classic configuration.

For 1988, the elimination of the stepped-up import tariff on over-700cc motorcycles brings new interest to the mid-size V-Twin class. All the major Japanese models have been brought back up to 750cc or larger displacements, along with other significant improvements. And the sole non-Japanese contender, Harley’s 883 Sportster, has benefitted from two years of refinement since being introduced with H-D’s Evolution engine technology.

Also, the fall of the dollar against the yen has equalized prices; the contenders in this class now range from the $3999 of the Suzuki Intruder and Kawasaki Vulcan to $4698 for the Honda 800 Shadow. In between are the Harley Sportster at $4322 and the Yamaha Virago at $4099.

With so many new factors to consider in the 750 VTwin class, we thought it time to take a close look at all the contenders, to find the comparative strengths and weaknesses of what many people consider the perfect size and type of motorcycle. Some of the results were utterly predictable; others came as quite a surprise.

HARLEY-DAVIDSON 883 SPORTSTER

Harley’s 883 Sportster is old, a design that predates lava lamps, hula hoops and President Kennedy. The first Sportster was built in 1957, and even then it used an overhead-valve conversion of an older Harley side-valve engine. Since then, just about every part in its engine and chassis has been changed, upgraded and improved.

Still, despite the facelifts, the Sportster is showing its wrinkles. While performance may not be paramount fora cruiser, feel is. And in too many ways, the smallest Sportster simply doesn’t feel as good as its competition.

Several characteristics of the Sportster’s 883cc engine are largely responsible for that. First, this long-stroke, 45degree V-Twin lacks any of the engineering tricks or rubber mounts that can smooth out that configuration. In other words, it vibrates. The handgrips shake, the footpegs quake and the thinly padded seat buzzes so badly above 3000 rpm in top gear (just over 58 mph) that you might think your buns are getting an electroshock treatment.

Second, the 883cc engine isn’t very powerful. It uses the same massive crankshaft as the Sportster 1200, which smoothes out low-speed running at the expense of acceleration; and the carburetion provided by the new constant-velocity Keihin is precise, if slightly lean. But while the engine may be adequate for simply carrying the Sportster down the road, it fails to add excitement. The 883 is not only the slowest V-Twin in this comparison by measure, it commits the less-forgivable crime of feeling slower than its numbers.

Aside from not being much of a goer, the 883 isn’t much of a stopper, either, continuing a Harley tradition of higheffort front brakes. Again, the bike measures better than it feels: Its stopping distance from 60 mph was the shortest of the five. But braking the Sportster that hard requires a white-knuckled, near-painful squeeze, a feature the company says is intended to prevent front-wheel lockup during a panic stop—sort of a blue-light-special ABS. In partial compensation, the Sportster rear brake is excellent, with good feel and controllability.

The rest of the Sportster is much better than its front brake and engine. Of the machines in this comparison, the 883 is the best-handling, able to corner with dreadnought stability and lean farther than most riders would care to go before dragging its footpegs. The front fork absorbs most bumps, though the bigger ones sneak past the short-travel rear shocks and thin seat to pound the rider’s back. Nonetheless, the Sportster chassis is the class of this field.

In riding position, the Sportster is simply different. The pegs are more rearward than those on the other bikes, and are splayed wide because of their location and the broad engine cases. The handlebar rises only a few inches and sweeps back only slightly, more like a dirt-bike bend than the chopperish pullbacks on the other cruisers. Overall, the position is acceptable, even if the peg-to-seat distance is a bit short and the seat hard.

If you desire, the Sportster can easily be given a more cruiser-esque riding position: Just add highway pegs and one of the many bends of pullback handlebars available. But as delivered, it’s configured more as a standard motorcycle than the Japanese V-Twin cruisers. This is one absolutely positive benefit of the Sportster's age: It’s more a 1960s roll-your-own bike than a 1980s specialty machine.

In the end, that ability to be owner-customized may be the Sportster’s chief appeal. It’s also quite possible to convert the engine from 883cc into the much more desirable 1 200cc displacement. And there is a near-infinite number of performance, comfort and dress-up accessories available for the 883, from both Harley-Davidson and the strong Harley aftermarket.

But as delivered, the 883 leaves much to be desired.

HONDA 800 SHADOW

With its early Shadow models, Honda has been accused of copying the form of American V-Twins without getting the soul right. That was certainly true of the revvy, buzzy, six-speed engine of the original 1983 Shadow 750. Over the years, Honda has sacrificed small amounts of the original Shadow’s peak power in the search for more torque and V-Twin feel. This year, Honda has carried that trend even farther and assigned an engineering team a very special task: Take the company’s V-Twin customs and inject a healthy measure of soul. With the Shadow 800, Honda succeeded almost too well.

A big Twin’s feel comes from its engine, and that’s where the engineers concentrated their efforts. The demise of the over-700cc tariff allowed the Shadow’s 699cc displacement to grow back to and beyond its original 750 size; so, it was given a longer stroke to bring it all the way up to 800cc. The engine was retuned for lower-rpm power and a healthy exhaust note. The six-speed gearbox was replaced with a four-speed so the engine will, according to a Honda spokesman, “have a long pull through each gear, for the right feel.”

It worked: The 1988 Shadow’s engine has charisma. The exhaust note at idle is a pronounced and deep V-Twin chuff, a bass beat that surprises in a motorcycle that has to meet an 80-decibel noise standard. The engine pulls well from 1000 rpm up to its 7000-rpm redline, but the lowspeed power is so strong that you find yourself short-shifting at 3000 rpm. And the 800 is a slower-spinning motor that has little of the old 750 Shadow’s buzziness.

But Honda seems to have taken the low-speed tuning a step too far, at least without substantially increasing the engine’s crankshaft mass. A lot of flywheel effect is required to smooth out the individual power pulses of a Twin at low speeds, and the Honda has comparatively little. So, during low-rpm acceleration, the power pulses can be felt as the engine hammers away to pull you along. Accelerate up a grade even at 50 mph in top gear on the Shadow, and those pulses are so strong that you can feel the damper in the driveshaft bouncing oft'its travel limits. The only relief is to downshift. And if you exploit the Shadow's strong low-end power during a parking-lot maneuver such as a tight U-turn, the engine just might suddenly flame out. It's not that the Shadow doesn't have a good engine; it's just that if the 883 Sportster has too much flywheel, the Honda has too little.

The four-speed gearbox also takes this V-Twin soul business a little too far. One of the best refinements Harley ever made to its big engines was the installation of a five-speed, and we’ve been suggesting a similar move for the Sportster for vears. Now we'll suggest it for Honda, as well: A four-speed gearbox simply doesn't provide enough usable gear ratios for this motorcycle. The Shadow isn’t ruined by it, but the bike would be better with a five-speed.

While the Shadow's engine is a mixture of charisma and excess, its chassis is simply competent. The brakes work well, the suspension is supple if slightly underdamped, and the handling good until the limits of ground clearance are reached.

The 800’s riding position is a slightly downsized version of the 1 100 Shadow’s feet-out. leaned-back posture, and somewhat controversial. We added a sissybar (a $78 Hondaline option) so a duffle bag could be more securely strapped to the rear seat, providing needed back-support during long rides. Most of our riders loved the resulting spread-out riding position, but one thought the pegs weren't forward enough, and another simply thought it all too weird to be acceptable. All agreed that the seat padding could have been a bit thicker, but with a single exception. our test riders found the Shadow reasonably com fortable.

Overall, the Shadow was impressive both for its competence and its torquey. good-sounding engine. A little more flywheel and a five-speed gearbox would move it significantly closer to perfection.

KAWASAKI 750 VULCAN

To understand the Vulcan 750, you really only need to know this: The same engineer who designed the original Ninja 900 engine designed the Vulcan’s V-Twin. Thus, while other companies tried to replicate the feel and look of a Harl ey-Davidson, Kawasaki couldn't help but design something more performance-oriented. But in its emphasis of function, Kawasaki has also built, for a class where style and character are everything, a motorcycle that is . . . well, almost characterless.

On paper, the specifications of the Vulcan engine are impressive. A 55-degree, liquid-cooled V-Twin, it uses double overhead camshafts, four valves per cylinder and four sparkplugs. It has a large bore and a short stroke, which helps explain its high, 8500-rpm redline. Carburetion is semi-downdraft, and engine vibration is quelled by both a counterbalancer and rubber engine mounts. This sounds more like a description of a race engine than something intended to power a mild-mannered street cruiser.

In practice, the Vulcan is probably the most powerful of these mid-size V-Twins, though the lighter Suzuki Intruder slightly outperforms it. And the Vulcan also is the smoothest-running. But perhaps because of the compromises incurred with a cruiser exhaust system and engine tune, the promise of the specifications doesn't make the Vulcan V-Twin a Ninja in a Harley suit.

To the contrary, the Vulcan has the engine with the fewest V-Twin characteristics. It pulls smoothly through a flat, seamless powerband that begins low and reaches almost to redline. Gearshifts are quick and easy, and the whole engine experience is in the Japanese mainstream; judged by feel alone, the Vulcan engine could just as easily be a larger version of Kawasaki’s EX500 parallel-Twin.

The chassis is somewhat mainstream as well, with a greater emphasis on comfort and performance than found on its competitors. The dual-disc front brake gives near two-finger stopping power, and the wide, well-padded seat is the best of the bunch. The Vulcan leans its rider back slightly, with his feet in front, a standard cruiser position without quite as much slouch as with the Shadow. Again, a duffle bag to lean against can turn the Vulcan into a quite acceptable long-distance ride, and its passenger accomodations are the best.

The Vulcan is also quicker-steering than the other VTwins, so it demands slightly more rider attention to avoid drifting off course. Its suspension is air-adjustable at both ends, and the rear shocks actually have a reasonable amount of damping. Still, the Vulcan is far from being a backroad terror because of a shortage of cornering clearance.

All told, the Vulcan is a motorcycle that works well, but without the visual and sensual appeal of its toughest competition.

SUZUKI 750 INTRUDER

The Intruder 750 was designed in the U.S., but no one was more suprised than its creators when the first prototype arrived from Japan and looked just like the clay model they had shipped to Hamamatsu. This faithful reproduction of a U.S. Suzuki design resulted in the slickestlooking and most integrated of the V-Twin cruisers.

It al so has an exceptional engine that perhaps is the bike's strongest asset, although it’s not without flaws. Like the Honda and Kawasaki engines, the Intruder V-Twin is liquid-cooled, but with enough finning to conceal that fact and allow its radiator to be very small. Like the Harley, the Intruder has a 45-degree V-angle, but vibration is diminished by a crankshaft that offsets the two crankpins by 45 degrees. The Intruder’s cylinder heads each hold four valves, and the front head uses a downdraft carburetor, the only type that could possibly fit in the room provided.

In terms of performance, the Intruder engine has a broad and particularly torquey powerband. Rolling open the throttle at low speeds has the bike fairly leaping forward with a mild, torque-pulsing throb coming from the engine and driveline. It’s a tamer version of the same quaking that emanates from the Honda Shadow; with the Intruder, Suzuki seems to have struck a perfect balance between engine character and smoothness. The Intruder does vibrate, but the vibrations it emits tend to be the ones that soothe rather than electrify.

Wrapped around the engine is a small, narrow and light chassis, as simple and free of plastic parts as any machine from Japan. (All the fenders and sidecovers are steel on the Intruder.) When you ride it, you first notice its small size and low seat; while the riding position isn’t as expansive as the Honda’s, it’s not cramped, and the seat is comfortable.

New for the Intruder this year is a 2 1 -inch front wheel. It’s a welcome addition that has improved the steering and eliminated any tendency of the rakish front end to flop inward on low-speed turns, something that was a problem for previous Intruders. Around town, the bike feels light and maneuverable, and is stable and secure on the highway.

But the Intruder doesn't always retain that composure. Try aggressively to straighten a backroad on it, and it will begin handling like a refugee from the Sixties. The shocks have little damping and the frame is not a paragon of rigidity, so w hen pushed hard through a mediumto highspeed corner, the bike weaves as though it had the world's largest hinge between the wheels. No other motorcycle we've ridden in recent years handles as badly, though you do have to push hard to discover it.

So. in every way it's fair to say the Intruder is an exceptional motorcycle: in its styling, its engine character, its feel around town and its cruisability down the highway. And. unfortunately, if you ride it hard, you'll find its backroad handling equally exceptional.

YAMAHA 750 VIRAGO

When we tested the Virago 1 100 last year, we said that all it needed was more legroom, a better seat and better shocks. This year, Yamaha responded to two of those three requests, moving the footpegs two inches forward and installing a w ider and more adequately padded seat on both the 750 and I 100 Viragos, which share a common chassis.

It's that type of refinement that has made the 750 Virago the competent machine it is. With its two-valve, aircooled engine, it is Japan’s simplest V-Twin. Few sacrifices have been made for that simplicity, even though the Virago could use more and better engine performance.

But the Virago has plenty of good things to offer. The new seat is truly comfortable, the riding position is no longer cramped—if not quite as expansive as that of the Shadow or Vulcan—and the handling is excellent by cruiser standards. The front fork works well, and the rear shocks perform adequately until faced with a badly surfaced road; for that condition, slightly more wheel travel and better shocks are still needed. But the Virago steers easily and lightly, has excellent stability, and feels more like a standard motorcycle of a few years ago than it does a typical cruiser. Only its limited cornering clearance allows it to be out-handled by the Sportster. But unlike the Harley, the Virago has excellent twin-disc front brakes, sharing top rating with those of the Vulcan.

HARLEY-DAVIDSON 883 SPORTSTER

$4322

HONDA SHADOW 800

$4776

KAWASAKI VULCAN 750

$4099

SUZUKI 750 INTRUDER

$3999

YAMAHA VIRAGO 750

$4148

And in all honesty, there’s nothing really wrong with the Virago’s engine. It runs smoothly until it nears its 7000rpm redline, buzzing only over the last 1000 rpm. In the quarter-mile, it is only a few tenths slower than the very quick Intruder or Vulcan.

But the Virago engine is another case of adequacy rather than excitement. Its isn’t particularly powerful at low speeds or in the mid-range, and it loses roll-on contests to its quicker competition. A quick pass demands a downshift or two, often putting the Virago up into the buzzy part of its operating range. Unlike its 1 100 sibling, the Virago 750 isn't a machine that likes to be short-shifted.

What results, then, is a machine that impresses with its competence, but lacks a lustful engine. If only it had another 50cc and more torque, it might be top cruiser.

But it doesn’t.

THE BOTTOM LINE

During the course of this comparison, we were continually reminded that there’s a reason bikes are called MOTORcycles. The machines in this comparison with outstanding engines were the ones that charmed us; those with more boring engines did not.

With that in mind, we can’t help but tell you that the two bikes that are offered in near-identical trim with larger-displacement engines—the Sportster and the Virago—are considerably happier machines in their larger form. In both cases, the extra torque of the big engine transforms the motorcycle, making it much more desirable. If you’re drawn by either the Virago or the Sportster, and there is any way you can possibly afford the larger version, buy it.

But among the machines we actually tested, the 883 Sportster unamimously brings up the rear. Harley’s leastexpensive model is slow, vibrates and is uncomfortablé. There certainly are reasons to buy it: resale value, its ease of modification, the Harley name on the gas tank, its forthright mechanical honesty. But none of those reasons have anything to do with the riding experience it provides; and that experience leads us to conclude that although Harley builds some supdrb motorcycles, the Sportster 883 isn't one of them.

In fourth place is the Vulcan 750, a competent but unexciting motorcycle. Its strength is its comfort, and for a long trip, it’s the pick of this litter. But Kawasaki’s designers would make better use of the Vulcan’s high-tech, if clumsily styled, engine if they would let it breathe freely in a sporting chassis, perhaps as a competitor for Honda’s Hawk GT.

In third, very near the front-runners, is the Virago. It is comfortable and performs well, but it needs more torque and engine character to move to the front of the cruiser ranks.

That leaves the Honda Shadow and the Suzuki Intruder vying to be the best mid-size cruiser. And on this matter, our riders split ranks. All liked the Suzuki’s looks and feel, but those who value twisty-road handling placed the Honda in front. Others thought that less important for a cruiser, and chose the Suzuki.

In the end, we’ll leave the decision split. The Honda is the V-Twin with the most well-rounded performance; the Suzuki the one with the most visceral and visual appeal.

Either is a very desirable motorcycle. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue