Against All Oz

RACE WATCH

A tale of survival in the world's shortest six-days

RON LAWSON

IT WAS BOUND TO BE A STRANGE event, right from the start. First of all, it was an International Six-Day Enduro that only lasted four days. Second, it was a world competition that could not crown a world champion. And strangest of all, it was Australian.

Perhaps that last point explains the other two. The event was the Australian Four-Day Enduro; and to understand why it even happened, you have to understand something about Australia, a country like no other in the world. In fact, the only country that bears even a slight resemblance to Oz is the United States; the two have more in common than either would like to admit. Australia and the U.S. both are countries of great expanse that have large bases of motorcycle enthusiasts. Yet both are countries of alternating greatness and despair in the world of motorcy-

cle sports. Both can boast of world champions in roadracing, for example, but have shown the ability to produce downright dismal results in many other areas of racing.

One of those other areas is enduro competition. In the rea! ISDE, both America and Australia still await their first major victory. And since the ISDE is, with rare exception, always held in Europe, both teams have to travel overseas, and are terribly disorganized once there.

A few years ago, though, the Australians came up with what sounded like a perfectly reasonable solution to their problem: Hold the ISDE down under. So, they applied for a SixDays event: and in late 1984, the FIM awarded the 1988 ISDE to Australia—a move that would have tied in perfectly with the country's Bicentennial celebration in 1988.

We say “would have" because, to

simplify a long story, FIM approval to run the ’88 ISDE in Australia ultimately was rescinded. The FIM had growing concerns about an appalling lack of organization within the involved motorcycle-sanctioning bodies in Australia, and pulled its approval, awarding the ’88 ISDE to France. That last-minute decision left the ACCU (Australia’s equivalent of the AMA) with a grant from the Australian Bicentennial Committee and nothing to spend it on.

So, the Aussies came up with another simple solution: Hold the event anyway. Once the pressure associated with holding an ISDE was gone, all the problems were eliminated with amazing haste, and a non-FIM-sanctioned event became reality. But instead of an ISDE, it was an IFDE, an International Four-Day Enduro. And the ACCU made sure all the top countries would participate simply by paying for their airfare with the bicentennial funds.

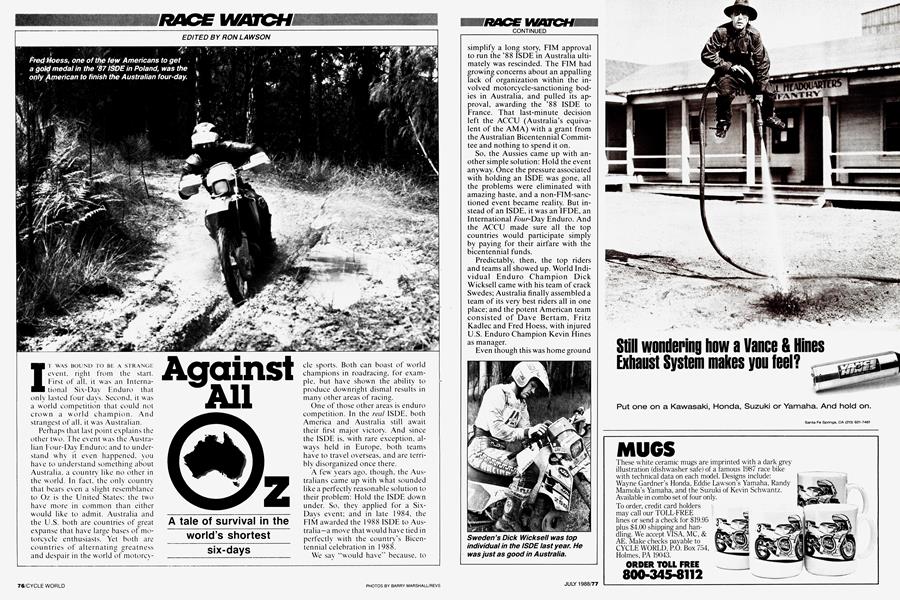

Predictably, then, the top riders and teams all showed up. World Individual Enduro Champion Dick Wicksell came with his team of crack Swedes; Australia finally assembled a team of its very best riders all in one place; and the potent American team consisted of Dave Bertam, Fritz Kadlec and Fred Hoess, with injured U.S. Enduro Champion Kevin Hines as manager.

Even though this was home ground

for the Australians, it was just as hard as ever for the traveling Americans. In fact, things were even worse than in Europe. For one, the Americans had no motorcycles. Hoess and Bertram planned on buying bikes after they arrived, but soon discovered there were precious few dirt bikes for sale in the entire country.

After searching high and low, Hoess finally found a new Kawasaki KX250, but Bertram was forced to rent a KTM 350—a machine he was completely unfamiliar with. Kadlec had the foresight to arrange a Yamaha TT350 ahead of time, but as soon as he rode the machine he discovered something he hadn’t counted on: He didn’t like it.

That made a tough event even tougher. “If this were two days longer, it would have been tougher than any Six-Days I’ve ridden,’’ Bertam commented. The combination of relentless rain, tight trails and long hours in the saddle soon took its toll on the American team. By the start of Day Three, both Bertam and Kadlec had dropped out.

“I lost more points in one section than I had in all the ISDEs I’ve run put together,” Kadlec confessed of a section in which he got lost. Bertram’s luck was even worse. “I was leaking coolant,” he said, “and couldn't even tell because the bike was so wet from the rain. It didn't make it.” Only Hoess remained in the competition, despite riding almost an entire day without a shift lever. By the time it was all over, the U.S. team was fifth overall with its one finisher. The Australian home team of Geoff Ballard, Ricky Madden and Brook Flanagan took the team honors, while Sweden's unstoppable Wickseil was top individual.

So what did it all prove? For the Australians, quite a lot. For one, they learned that their country can successfully put on a world-class enduro—a fact that allegedly did not escape the FIM’s notice. And two, the IFDE proved that the unheralded Australian enduro riders can not only run with the best in the world, but can beat them.

That last point was especially important to the Americans. After all, the U.S. team riders like to think that’s one more thing they have in common with the Australians. And they just might be right. >

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialAmerican Racewatching's Finest Hour

July 1988 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeBad Day In Daly City

July 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsRadio Daze

July 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupSafer Cycling Through Electronics

July 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

July 1988 By Alan Cathcart