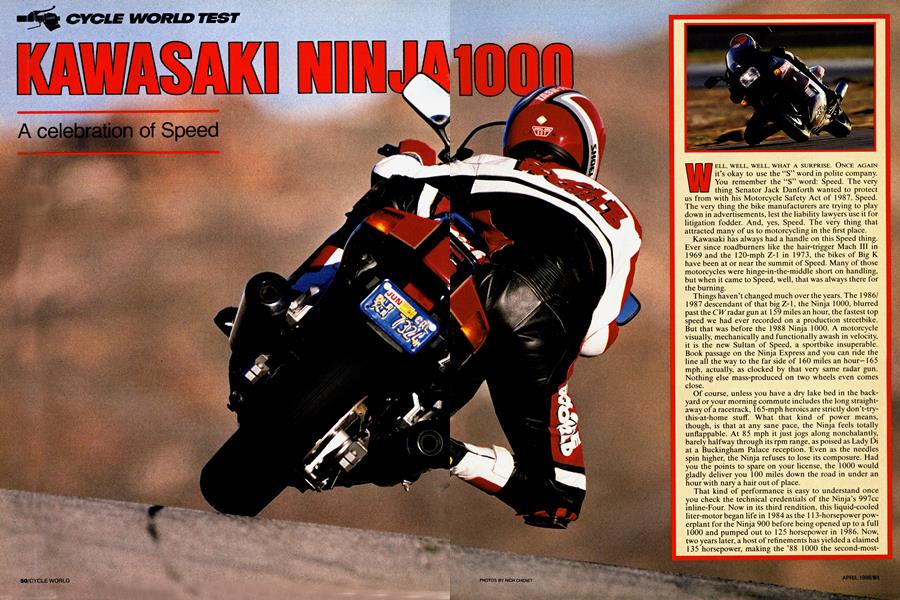

KAWASAKI NINJA 1000

CYCLE WORLD TEST

A Celebration of Speed

WELL, WELL, WELL, WHAT A SURPRISE. ONCE AGAIN it’s okay to use the “S” word in polite company. You remember the “S” word: Speed. The very thing Senator Jack Danforth wanted to protect us from with his Motorcycle Safety Act of 1987. Speed. The very thing the bike manufacturers are trying to play down in advertisements, lest the liability lawyers use it for litigation fodder. And, yes, Speed. The very thing that attracted many of us to motorcycling in the first place.

Kawasaki has always had a handle on this Speed thing. Ever since roadburners like the hair-trigger Mach III in 1969 and the 120-mph Z-l in 1973, the bikes of Big K have been at or near the summit of Speed. Many of those motorcycles were hinge-in-the-middle short on handling, but when it came to Speed, well, that was always there for the burning.

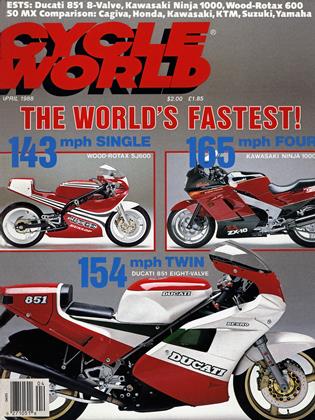

Things haven’t changed much over the years. The 1986/ 1987 descendant of that big Z-l, the Ninja 1000, blurred past the C Wradar gun at 159 miles an hour, the fastest top speed we had ever recorded on a production streetbike. But that was before the 1988 Ninja 1000. A motorcycle visually, mechanically and functionally awash in velocity, it is the new Sultan of Speed, a sportbike insuperable. Book passage on the Ninja Express and you can ride the line all the way to the far side of 160 miles an hour—165 mph, actually, as clocked by that very same radar gun. Nothing else mass-produced on two wheels even comes close.

Of course, unless you have a dry lake bed in the backyard or your morning commute includes the long straightaway of a racetrack, 165-mph heroics are strictly don’t-trythis-at-home stuff. What that kind of power means, though, is that at any sane pace, the Ninja feels totally unflappable. At 85 mph it just jogs along nonchalantly, barely halfway through its rpm range, as poised as Lady Di at a Buckingham Palace reception. Even as the needles spin higher, the Ninja refuses to lose its composure. Had you the points to spare on your license, the 1000 would gladly deliver you 100 miles down the road in under an hour with nary a hair out of place.

That kind of performance is easy to understand once you check the technical credentials of the Ninja’s 997cc inline-Four. Now in its third rendition, this liquid-cooled liter-motor began life in 1984 as the 113-horsepower powerplant for the Ninja 900 before being opened up to a full 1000 and pumped out to 125 horsepower in 1986. Now, two years later, a host of refinements has yielded a claimed 135 horsepower, making the ’88 1000 the second-mostpowerful motorcycle ever to set tread on a showroom floor. Only Yamaha’s original V-Max, with 143 ponies at the ready, was brawnier.

Kawasaki’s quest for more power and performance over last year’s 1000 led the engineers down two avenues: a more-efficient cylinder-head design, and less weight in certain engine components. The new head employs a narrower included valve angle (30 degrees vs. 34.9) than on the previous 1000, and intake ports that have virtually a straight shot into more-compact combustion chambers, entering the engine at a 45-degree downward angle. The compression ratio is up to 11 : l from last year’s 10.2: l, and as a nice finishing touch, the area around each intake valve seat is hand-polished at the factory by “senior technicians,” as Kawasaki likes to call them.

So radical is the engine’s intake-port angle that the tops of its canted Keihin carbs actually sit higher than the uppermost part of the cylinder head, requiring those 36mm CV units to be of a semi-downdraft design. And to take full advantage of the new head’s power potential, the carbs are fitted with plastic velocity stacks inside the airbox to further smooth and tune the flow of intake air.

As on the 750 Ninja, the new 1000 utilizes individual finger-type cam followers to open its 16 valves, instead of the eight dual-finger followers used on the previous big Ninja. Unlike the 750 Ninja, though, which has threaded adjusters, the 1000’s valve lash is regulated by tiny shims under the valve retainers. This allows the 1000’s followers to be even smaller and lighter than the 750’s. Overall, in fact, the total weight of the new engine’s valve train is 27 percent less than that of its l986-’87 predecessor.

This cylinder-head rethink has reaped many benefits. The increased airflow has so improved the breathing that high-rpm power is substantially increased, while the lighter valve gear lets the engine run easily in those upper rev ranges, evidenced by the increase in redline from 10,500 rpm on the old 1000 to 11,000 on the new. The improved breathing also has allowed the camshafts in this year’s engine to have slightly less-radical timing than before, which, in real-world terms, has allowed the increase in high-rpm power not to come at the expense of low-end or mid-range performance.

Complementing all this top-end hot-rodding is a weightreduction program at the bottom of the engine, where the five-bearing crankshaft was pared by 2.4 pounds. This was done not to drop engine weight, but rather to reduce overall flywheel inertia—14 percent, according to Kawasaki— for quicker acceleration and snappier throttle response. The ’88 bike’s flat-top pistons and steel connecting-rod assemblies are slightly lighter, as well, yielding enough of a reduction in reciprocating weight, claims Kawasaki, that the higher redline does not endanger the engine’s reliability.

The outcome of all this mechanical tweaking is an engine like no other you’ll find in an Open-class sportbike. In a way, it’s as if the slightly peaky Ninja 900 engine was combined with last year’s torque-intensive 1000; whatever the cause, the effect is superb. Wind the tachometer to 8000 rpm as you work through the six-speed gearbox and you’re effortlessly rewarded with the impressive lunges of forward motion that make liter-class motorcycles so much fun. Give the go-ahead to use the remaining three grand worth of revs, though, and the Ninja makes a quick but smooth transition into an asphalt-gulping, upper-rpm surge that is kick-in-the-pants exciting. Below 8000 rpm, this is a quick motorcycle; above that mark, it’s one that is hell-bent for the “S” word. The Ninja’s dragstrip performance bears that out; With a 10.76-second quarter-mile clocking, it’s the quickest production motorcycle Cycle World has ever tested.

Happily, the Ninja’s chassis has been reworked to cope with the engine's colossal power output. The frame, a perimeter-style layout simiiiar to last year’s steel unit, is now made entirely of aluminum. Dubbed an “e-box” because its two side rails take on a egg-like oval shape when viewed from above, the frame is claimed to weigh 34 pounds, almost 10 pounds less than the ’87 Ninja’s. The steeringhead angle has been pulled in from 28 to 26.5 degrees for quicker, more-accurate cornering, and in an effort to keep the front end from flexing, the fork-tube diameters have been upped lmm to 4lmm, with an integral brace within the fender. A large-diameter axle is held securely by dual pinch-bolts on each side.

While the ’88 bike’s rear shock is similar to the ’87’$, it lives amidst a different linkage that compresses it only from the bottom instead of from both ends as before. For added rigidity, the aluminum swingarm is now constructed of larger box-section extrusions and pivots on two needle bearings on its left (drive-chain) side. The right side of the swingarm rides on only one needle bearing, along with a caged ball-bearing that restricts lateral movement.

Also included in the chassis upgrade were the wheels and tires. Low-profile Dunlop K455 radial tires mount to new cast wheels, each an inch wider than the '87 bike’s hoops. Wheel diameter is different, as well, with an 18incher in the rear and a 17-incher up front, rather than the dual 16-inch rims on last year’s Ninja. That leaves Suzuki’s Katana 1100 as the only big-bore sport-oriented bike still using the once-fashionable 16-inch front wheel.

As if all these chassis improvements weren’t enough, the new bike even is lighter than the qld one. But while Kawasaki claims a 35-pound weight reduction, our scales don’t agree, showing the ’88 model, at 541 pounds dry, to be just 17 pounds lighter than the ’86-’87 version.

To some, this may seem bad news, since the previous 1000 was a real porker, some 20 pounds heavier than a Honda Hurricane 1000 and more than 80 pounds on the Orson Welles side of a Suzuki GSX-Rl 100. But the good news is that this latest 1000feels as if it actually has been relieved of at least 30 or 35 pounds. For that, you can thank the bike’s lower center of gravity, quicker steering geometry, l5mm-lower seat and, to a lesser extent, its 15mm-shorter wheelbase.

Indeed, there’s no question that this Ninja is a handler. With the air-adjustable shock charged to about 15 psi and its accompanying rebound-damping adjuster clicked onto the second of four settings, the 1000 turns easily and accurately during fast street rides, never doing anything untoward when banked over hard in your favorite corner. And even though the bike is equipped with a centerstand—an item that usually gets the heave-ho on other companies’ sporting products—cornering clearance is abundant.

A bike this heavy usually makes its heft evident in quick, side-to-side transitions, but the big Ninja snaps through situations of this kind with ease. The Dunlops remain planted, and the brakes—now with floating front rotors and dual-piston calipers that use a smaller leading piston than trailing piston-admirably take care of the anchor-throwing duties. The brakes are so good, in fact, that the Ninja could be yanked down from 60 miles an hour in just 107 feet, the shortest braking distance we’ve ever recorded from that speed on any motorcycle.

Only late-brakers will find fault with the Ninja’s street handling. Like most wide-tired motorcycles, the 1000 tends to sit up while banking and braking at the same time, but not as much as, say, a Yamaha FJ1200 or Suzuki Katana 1100. Still, it’s better to get all the braking done in a straight line before pitching the Ninja into a turn.

Ridden at club-racing speeds on a racetrack, more chinks become apparent in the Ninja’s handling armor. As lap times drop, the rear tire starts sliding under power, the front end begins feeling vague and the brakes becomes less sure. Remember, though, that this is a sporty road machine, not intended for the rigors of racing; even so, our inhouse Pro roadracer believes that with sticky productionracing tires and some suspension fine-tuning, the Ninja— especially on long, fast tracks where the throttle cable can be strained early and often—will give the GSX-Rs and FZRs a run for their money.

Riders who prefer to use their bikes for going places rather than for stocking the mantlepiece with racing trophies will be glad to know that the Ninja makes an excellent sport-touring mount—with a bit more emphasis on the “sport” half of that description, however. While its seat and rear suspension (even with no air in the shock) don’t cuddle the buns as comfortably as a Katana 1 100’s or Hurricane 1000’s, neither will an all-day ride inflict GSXR wrist-lock or FZR knee-kink. A seat with a skosh more padding and handlebars with about an inch of additional rise would help, and riders intent on creating a sporttourer ne plus ultra will want to invest in a more-softly sprung rear shock. But at least tingling hands and feet won’t be a problem; thanks to the engine’s counterbalancer and rubber-isolated front motor-mounts, vibration, at speeds below 100 mph, anyway, is all but non-existent.

Altogether, then, the Ninja 1000’s combination of power, handling and comfort puts it firmly in the middleground of lOOOcc sportbiking. It’s an exciting, versatile powerhouse that can mix it up with the repli-racers, yet is still capable of galloping hundreds of miles down the road without breaking a sweat. Even if that all-around approach to building a sportbike doesn’t appeal to you, let’s at least take our hats off to Kawasaki for building the world’s quickest and fastest streetbike, and for having the grapefruit-sized cojones not to back away from its tradition of Speed. 0

KAWASAKI

NINJA 1000

$5999

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

April 1988 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

April 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Departments

DepartmentsLeanings

April 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupYen And the Art of Motorcycle Marketing

April 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

April 1988 By Kengo Yagawa