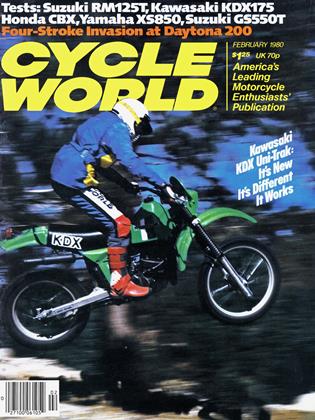

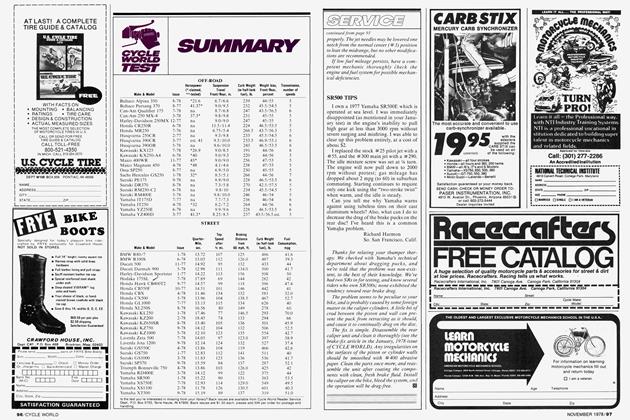

KAWASAKI KDX175

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Yamaha introduced the last really new rear suspension seen on a production motorcycle. The year was 1974, and the mono-shockers reached the showroom floor only after a couple of developmental years on the Grand Prix circuit.

Now Kawasaki has come along with another new idea in rear suspension, the Uni-Trak, and has done the near-impossible in offering the Uni-Trak to the public just one model year after the idea appeared on the team bikes.

The speed of introduction wasn't the only surprise. Most new developments arrive first on motocross machines, then filter down to the enduro bikes. And usually the bigger versions get the new' stuff, followed by the smaller jobs picking up the handme-downs.

Instead, Kawasaki’s production UniTrak makes its debut on a KDX. an enduro bike. And the system comes on the 1980 KDX 175, while the KDX420 and KDX250 make do with conventional rear suspension.

Why? In part because the 175 enduro class is popular and becoming moreso. which brings lots of development work from the various rival factories. Also, the KDX 175 continues Kawasaki’s trend, that of building playbikes from motocross parts.

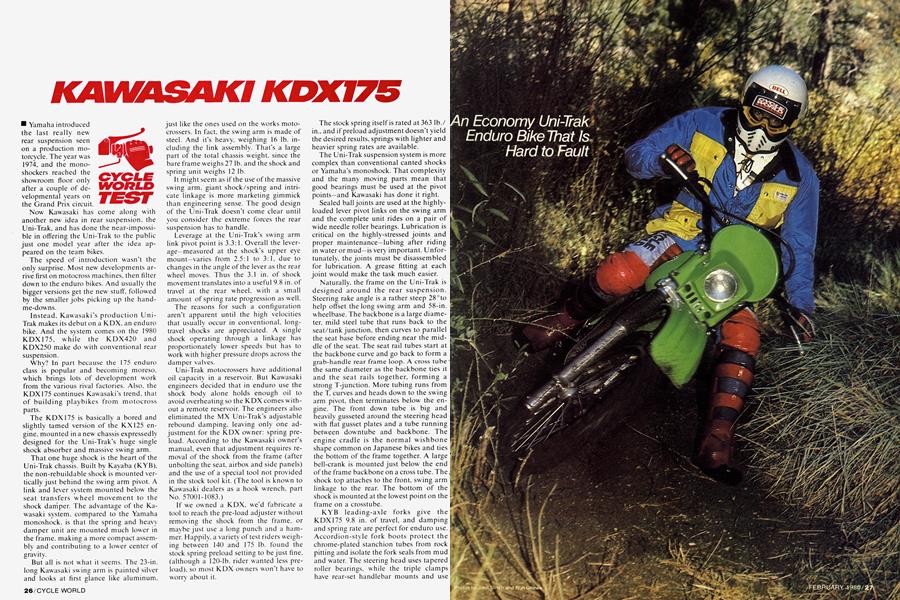

The KDX 175 is basically a bored and slightly tamed version of the KX125 engine. mounted in a new chassis expressedlv designed for the Uni-Trak’s huge single shock absorber and massive swing arm.

That one huge shock is the heart of the Uni-Trak chassis. Built by Kayaba (KYB), the non-rebuildable shock is mounted vertically just behind the swing arm pivot. A link and lever system mounted below the seat transfers wheel movement to the shock damper. The advantage of the Kawasaki system, compared to the Yamaha monoshock, is that the spring and heavy damper unit are mounted much lower in the frame, making a more compact assembly and contributing to a lower center of gravity.

But all is not what it seems. The 23-in. long Kawasaki swing arm is painted silver and looks at first glance like aluminum. just like the ones used on the works motocrossers. In fact, the swing arm is made of steel. And it’s heavy, weighing 16 lb. including the link assembly. That's a large part of the total chassis weight, since the bare frame weighs 27 lb. and the shock and spring unit weighs 12 lb.

It might seem as if the use of the massive swing arm, giant shock/spring and intricate linkage is more marketing gimmick than engineering sense. The good design of the Uni-Trak doesn’t come clear until you consider the extreme forces the rear suspension has to handle.

Leverage at the Uni-Trak's swing arm link pivot point is 3.3:1. Overall the leverage-measured at the shock’s upper eye mount—varies from 2.5:1 to 3:1, due to changes in the angle of the lever as the rear wheel moves. Thus the 3.1 in. of shock movement translates into a useful 9.8 in. of travel at the rear w'heel. with a small amount of spring rate progression as well.

The reasons for such a configuration aren’t apparent until the high velocities that usually occur in conventional, longtravel shocks are appreciated. A single shock operating through a linkage has proportionately lower speeds but has to work with higher pressure drops across the damper valves.

Uni-Trak motocrossers have additional oil capacity in a reservoir. But Kawasaki engineers decided that in enduro use the shock body alone holds enough oil to avoid overheating so the KDX comes without a remote reservoir. The engineers also eliminated the MX Uni-Trak’s adjustable rebound damping, leaving only one adjustment for the KDX owner: spring preload. According to the Kawasaki owner’s manual, even that adjustment requires removal of the shock from the frame (after unbolting the seat, airbox and side panels) and the use of a special tool not provided in the stock tool kit. (The tool is known to Kawasaki dealers as a hook wrench, part No. 57001-1083.)

If we owned a KDX, we’d fabricate a tool to reach the pre-load adjuster without removing the shock from the frame, or maybe just use a long punch and a hammer. Happily, a variety of test riders weighing between 140 and 175 lb. found the stock spring preload setting to be just fine, (although a 120-lb. rider wanted less preload). so most KDX owners won’t have to worry about it.

The stock spring itself is rated at 363 lb./ in., and if preload adjustment doesn’t yield the desired results, springs with lighter and heavier spring rates are available.

The Uni-Trak suspension system is more complex than conventional canted shocks or Yamaha’s monoshock. That complexity and the many moving parts mean that good bearings must be used at the pivot points—and Kawasaki has done it right.

Sealed ball joints are used at the highlyloaded lever pivot links on the swing arm and the complete unit rides on a pair of wide needle roller bearings. Lubrication is critical on the highly-stressed joints and proper maintenance—lubing after riding in water or mud—is very important. Unfortunately, the joints must be disassembled for lubrication. A grease fitting at each joint would make the task much easier.

Naturally, the frame on the Uni-Trak is designed around the rear suspension. Steering rake angle is a rather steep 28°to help offset the long swing arm and 58-in. wheelbase. The backbone is a large diameter. mild steel tube that runs back to the seat/tank junction, then curves to parallel the seat base before ending near the middle of the seat. The seat rail tubes start at the backbone curve and go back to form a grab-handle rear frame loop. A cross tube the same diameter as the backbone ties it and the seat rails together, forming a strong T-junction. More tubing runs from the T. curves and heads down to the swing arm pivot, then terminates below the engine. The front down tube is big and heavily gusseted around the steering head with flat gusset plates and a tube running between downtube and backbone. The engine cradle is the normal wishbone shape common on Japanese bikes and ties the bottom of the frame together. A large bell-crank is mounted just below the end of the frame backbone on a cross tube. The shock top attaches to the front, sw ing arm linkage to the rear. The bottom of the shock is mounted at the lowest point on the frame on a crosstube.

KYB leading-axle forks give the KDX175 9.8 in. of travel, and damping and spring rate are perfect for enduro use. Accordion-style fork boots protect the chrome-plated stanchion tubes from rock pitting and isolate the fork seals from mud and water. The steering head uses tapered roller bearings, while the triple clamps have rear-set handlebar mounts and use double pinch bolts to secure the 36mm stanchion tubes. Front wheel feedback and steering precision are excellent, giving the rider confidence that the bike will go where he points it.

Brakes at both ends are shared with the KX125. The brake’s full-floating backing plate rotates in needle bearings. The torque arm has needle roller bearings where it attaches to the backing plate and a Heim joint at the frame mount. The needle bearings are sealed and a rubber cover protects the Heim joint. This is an expensive way to make a fully-floating rear brake, but it’s also the right way. In addition, the brake linkage parallels the swing arm and contributes to smooth, controllable stops regardless of terrain. The front brake is almost as good as the rear but needs more strength for expert level riders. However, the front brake does have good feel and progressive stopping power. Both brakes are unaffected by water crossings, stopping as well in the wet as in the dry.

The KDX engine is a modified KX125 powerplant. The center cases, most case covers, crankshaft and bearings are all the same. Changes have been made, however, to ensure proper power delivery for enduro riding, including the use of a cylinder with 10mm more bore, an external flywheel CDI, primary gear ratios reduced from 3:1 to 3.55:1, and the six internal transmission gear ratios lowered to improve low-end plonking and better match enduro riding. The tough clutch from the KX125 motocrosser remains unchanged. Naturally, the bike has primary kick starting, which doesn’t seem important until the bike is stalled in a precarious position with an out-of-control rider approaching fast.

The KDX cylinder is semi-trick with an Electrofusion bore surface and caged reed induction. Porting is milder than the 125 motocrosser and the exhaust port isn’t bridged. The Boyensen plastic reeds feed fuel from a 34mm Mikuni carburetor into the cylinder. The back of the two-ring piston is arched slightly to allow quicker fuel passage and small ports are provided from the intake tract to the rear set of transfer ports to feed the lower end of the engine on demand, regardless of piston position. This type of induction first appeared on the Honda CR250R a couple of years ago. It gets fuel to the lower end on demand, without drilling holes in the rear of the piston skirt and can be employed with existing cases, which cuts the cost of casting all new cases. Suzuki started the piston/case feed fad back in 1975 on RM models and the other manufacturers have found other ways to copy the concept without casting new lower cases and without directly copying Suzuki.

Plastic parts on the KDX are Kawasaki green and well-made. The tank holds 2.8 gal. of premix and is shaped like the Kawasaki factory motocrosser tanks. Side plates aren’t rear-set because side numbers aren’t required at most enduros. Fenders are great and not so great: The front is wide and long, and keeps mud and water off the operator. The rear is the right width but too short. When the rear wheel is spun in mud, the mud ends up on the back of the rider. An additional 6 or 8 in. needs to be added to the rear fender.

Because the shock rides in the place normally occupied by the airbox, the airbox is offset left of center. The large, oiled fuzzy foam air filter and plastic airbox brought mixed reactions from our staff. The airbox air inlets are protected from water splash by rubber spouts, and two rubber plugs can be removed from the top of the box for additional air flow in dry weather. The side plate doubles as the cover for the airbox and has a good waterproof seal. So what’s wrong with it? The filter is too deep for the box, so only the edges do any filtering. The large top surface is pushed against the cover and goes to waste.

The KDX doesn’t feel like a small motorcycle, which is easy to understand considering the 58-in. wheelbase and 36.9-in. seat height. It weights 237 lb. with a half tank of fuel, about 10 lb. heavier than a PE 175 and about 5 lb. lighter than an IT 175. But all of the test riders thought the bike weighed much less than it actually does. Most guessed the weight to be about 200 lb., a feeling derived from the low placement of the shock.

The long swing arm and 58-in. wheelbase make a slightly heavy front end. The front can be lofted with practice but it isn’t as easy as blipping the throttle. The heavy front combined with a solid frame and swing arm enhances steering precision, making dodging rocks and picking hard lines natural. The KDX goes exactly where the rider points it. Exactly.

Sliding corners on fire break roads is a blast on the little KDX. Full-lock 50 mph slides are easy as the rider dreams about beating Eklund or Springsteen at their own game.

Power is perfect for such a small displacement engine. Low-end pulling is strong and steady, with no loading up or sudden bursts or other bad manners. It will happily plonk and play trials bike all day, if that’s what you want. When the throttle is turned on, power progression is smooth, steady and controllable. Top end power is strong like an IT175, while low end plonking is comparable to a PE 175. Kawasaki has combined the best performance of both competitors into the KDX.

Climbing hills is fun on the Uni. It will top extremely steep hills in second gear and ones that look impossible in first. When it comes time to shift from second to first, the front wheel stays on the ground and the bike doesn’t try to loop. Low is very low and starting from dead stop halfway up a steep hill is possible with a good rider aboard.

Shifting is smooth and positive. The sixspeed transmission’s gear spacing isn’t as good as it could be, though. A noticable gap exists between second and third when trying to make a fast approach to a hill. Second will be wound too tight, yet the bike won’t pull hard in third. This jump in the gearing isn’t noticed on flat ground, just on steep grades. With six speeds, it should have been possible to eliminate the lag or move it up between the higher gears where it wouldn’t be so noticeable.

The suspension furnishes a firm ride over small objects and stutter bumps—not harsh, but suspension compliance isn’t as good as that of the KLX. When rough ground is encountered, the Uni-Trak behaves perfectly. It swallows up downhill w hoops as if they w ere flat ground, and the rougher the terrain becomes, the better the ride. Big jumps are a breeze on the KDX. Landings are pillow soft until the limits of the suspension are reached, then the rear bottoms with an audible thud. All of the controls are properly placed and the bike is comfortable to ride for hours at a time. Deep water crossings don’t affect the brakes and the saw-toothed pegs, brake pedal and ribbed shift lever aren’t slippery. The shift lever has a folding end but the complete end doesn’t fold, meaning it is still possible to bend the lever. It is better than a non-folding lever, but not much.

Several Kawasaki tests ago, we mentioned that the factory is offering American riders what amounts to American motorcycles, that is, the research and development are done in this country so the bikes will suit the needs of the people who’ll buy them.

This is especially so watn the KDX 175. At the expert level, Kawasaki now has one Jack Penton leading the enduro team. The KDX 175 was worked out as a potential overall winner.

The development wasn’t just limited to expert sections. Nor did it all take place in open country. Lots of guys in the southwest ride in the desert. And lots of guys everywhere else ride in the woods. The Kawasaki R&D team rode all across the country, from the Mojave to Michigan.

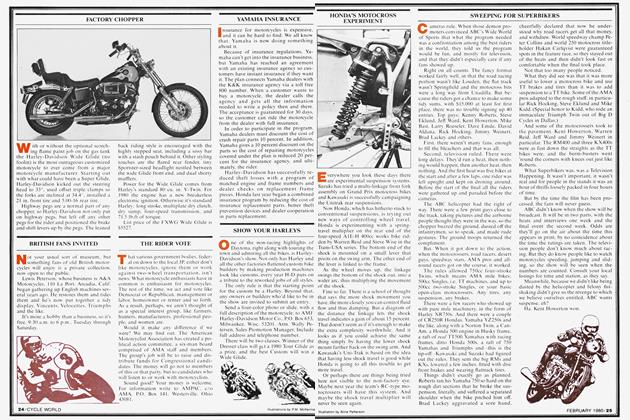

It shows. As the pictures here illustrate, the KDX 175 works in the woods. It will nip between trees and scamper across logs as easily as it swallows the whoops and sails across the sand dunes.

The Kawasaki KDX 175 does the job it was designed to do, and does it well. It is a serious enduro machine that can double as a play bike or anything in between.

Special mention should be made of the $1195 suggested retail price on the 175 Uni-Trak. That’s up to $100 less than last year’s prices on similarly-sized Japanese 175s. The difference between the KDX and some non-Japanese 175s is up to $400. This isn’t to suggest that the Kawasaki is a cheap motorcycle. It’s not. It’s just an enormous bargain.

It has the best suspension of any stock production 175 we have tested, but isn’t any better than a properly engineered conventional cantilever rear with Ohlins or Works Performance shocks. But of course no one furnishes Ohlins or Works shocks on 175 enduro bikes. To install either brand will lighten your pocket around $250. The little Uni won’t need an aftermarket shock or shock modifications. It works great as is. (It took Yamaha several years to get their monoshock working as well as the Uni-Trak does the first year.) With a suggested retail price of $1195 the KDX 175 has to be considered a serious threat in the highly competitive 175 enduro class. E9

KAWASAKI

KDX175

$1195