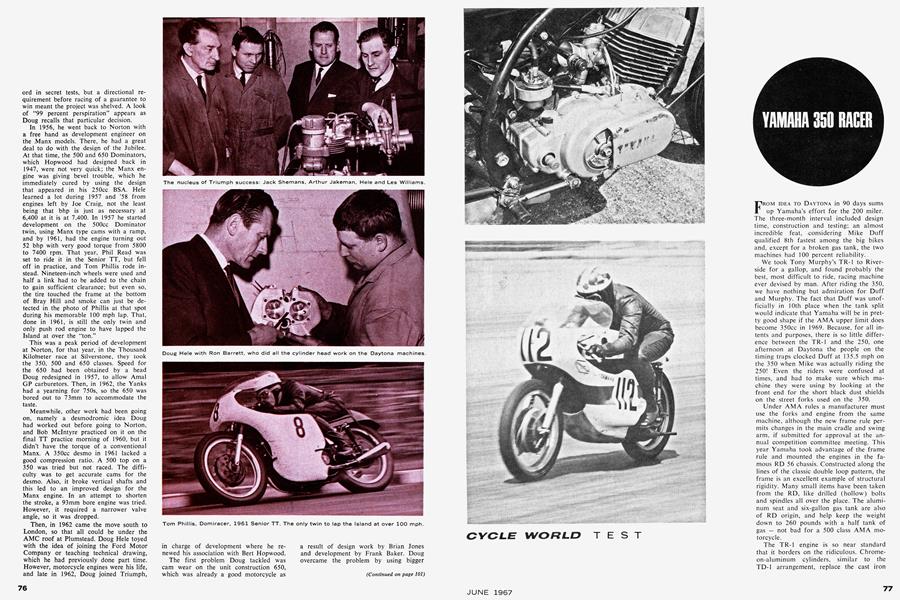

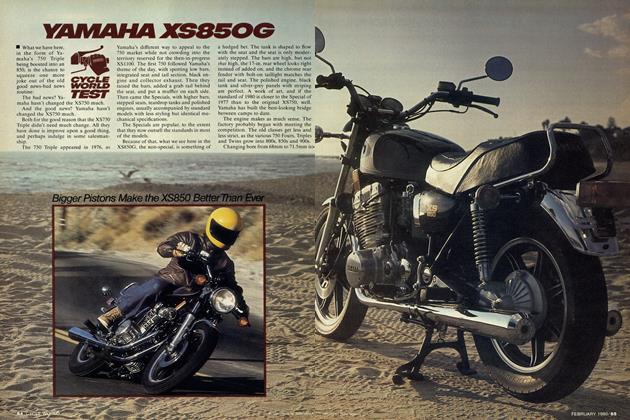

YAMAHA 350 RACER

CYCLE WORLD TEST

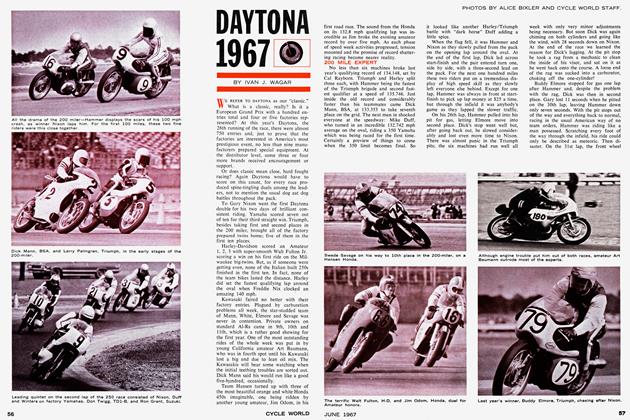

FROM IDEA TO DAYTONA in 90 days sums up Yamaha's effort for the 200 miter. The three-month interval included design time, construction and testing; an almost incredible feat, considering Mike Duff qualified 8th fastest among the big bikes and, except for a broken gas tank, the two machines had 100 percent reliability.

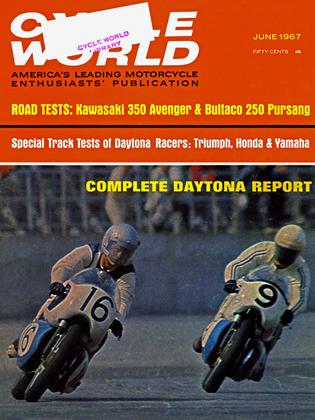

We took Tony Murphy's TR-1 to Riverside for a gallop, and found probably the best, most difficult to ride, racing machine ever devised by man. After riding the 350, we have nothing but admiration for Duff and Murphy. The fact that Duff was unofficially in 10th place when the tank split would indicate that Yamaha will be in pretty good shape if the AMA upper limit does become 350cc in 1969. Because, for all intents and purposes, there is so little difference between the TR-1 and the 250, one afternoon at Daytona the people on the timing traps clocked Duff at 135.5 mph on the 350 when Mike was actually riding the 250! Even the riders were confused at times, and had to make sure which machine they were using by looking at the front end for the short black dust shields on the street forks used on the 350.

Under AMA rules a manufacturer must use the forks and engine from the same machine, although the new frame rule permits changes in the main cradle and swing arm, if submitted for approval at the annual competition committee meeting. This year Yamaha took advantage of the frame rule and mounted the engines in the famous RD 56 chassis. Constructed along the lines of the classic double loop pattern, the frame is an excellent example of structural rigidity. Many small items have been taken from the RD, like drilled (hollow) bolts and spindles all over the place. The aluminum seat and six-gallon gas tank are also of RD origin, and help keep the weight down to 260 pounds with a half tank of gas — not bad for a 500 class AMA motorcycle.

The TR-1 engine is so near standard that it borders on the ridiculous. Chromeon-aluminum cylinders, similar to the TD-1 arrangement, replace the cast iron ones used on the standard R-l street machine. Port timing has, of course, been altered to go with the expansion chamber exhaust. From the factory the engines had only 6.5:1 compression ratio; but at Daytona it was lowered even further when a decision was made to use two head gaskets. The cylinders do, of course, have the original three port layout. Instead of the standard 28mm carburetors on the street version, the TR-1 has 30mm Japanese Amals with remote float chambers.

AMA rules only permit four-speed transmissions for 500 class bikes, and the standard R-l has a five-speed box, which meant one gear had to go. To retain the closest ratios, Yamaha chose to drop first gear entirely and leave second, third and fourth exactly where they were ratio-wise. A new top gear was designed to bring the new third and fourth closer together. Unfortunately, with a 4.9:1 top gear, first gear is just a little bit too high, even for Daytona, and the riders were forced to slip the clutch from two turns every lap. With the short power band, it must have been difficult to design ratios for Daytona. where a tall top gear is required. Had the engine been capable of more rpm, the gears could have been wider spaced, thus giving a better low gear. The situation was a little better when the machines were geared for 136 mph top speed, but when Murphy came through start/finish on Thursday's qualifying, with the wind behind him. the engine overrevved and blew. At that point, to allow a safety margin, the gearing was raised to give 142 mph at 9.500 rpm. In fact, when Duff qualified at 132.7 he was pulling more than the 142 mph gearing and was forced to lose time on the up-wind section. There is little doubt but what his speed would have been better had the correct ratio been fitted.

All of the Yamahas at Daytona used an autolube arrangement, where oil was metered into the inlet port proportional to demand. And, like the street-going models, only straight gasoline was used in the main tank. Oil for the pump was carried in the seat, which had a four-quart capacity. The system apparently worked very well — none of the machines seized during the week. Overrevving and ignition faults were the only causes of trouble.

The clutch, although more progressive than the engine-speed version fitted to TD-ls, is still somewhat of an off-on proposition. To make matters worse, the tachometer does not register when the clutch is disengaged. When trying to get off the line, the technique is to wind the engine up on the power band, or where you think the power band is, because the tachometer isn't working and you cannot be really sure, and then slip the clutch until the engine will pull the machine. Considering that the engine does not really pull well until 8,000 rpm, which represents almost 60 mph, and that engine failure is virtually certain if 9,500 rpm is exceeded by very much, it is then better understood why the machine is difficult to ride. As bad as it was for us, with no other engines running, it must have been almost impossible for Duff and Murphy with all of the noise and hubbub on the grid at Daytona.

At Daytona all six of the special Yamahas used electronic ignition systems, which gave trouble on two of the machines. Immediately after the race the complete systems were shipped to Japan for examination, to try to rectify the problem. A standard magneto was fitted to the 350 for our ride.

At this point it looks as though Yamaha are very close to having a big category winner, despite the 150cc displacement disadvantage. and only a good rider/technician is required to sort out minor items.

Yamaha claim 49 horsepower, which must be quite accurate because the machine pulls so much gear. It is frightening to think that Yamaha has only to build 100 350s with five-port engines, submit them for AMA approval and then go racing with anyone. The five-port cylinder will give at least another eight horsepower.

A five-speed gearbox would also make the TR-1 more competitive. As it is now, the 250 will better the 350 on acceleration, but the 350 probably has a slight edge on top speed. So far, we cannot get a straight answer on whether the AMA will permit five-speed boxes when the limit is lowered. However, it does seem strange that a manufacturer is forced to reduce the number of speeds when a machine is converted for racing. But, whichever it is, it matters little; whether the engine is twostroke or four, everyone will be in the same boat. It is conceivable that the TR-1 could win on a twisty course in its present form, and the fact that it is so good with so little development time, is food for thought. ■