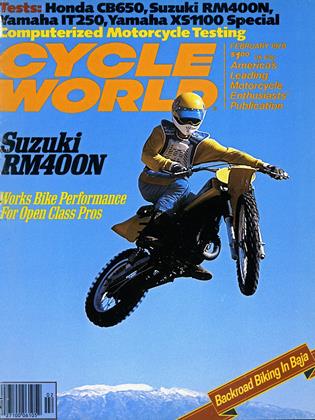

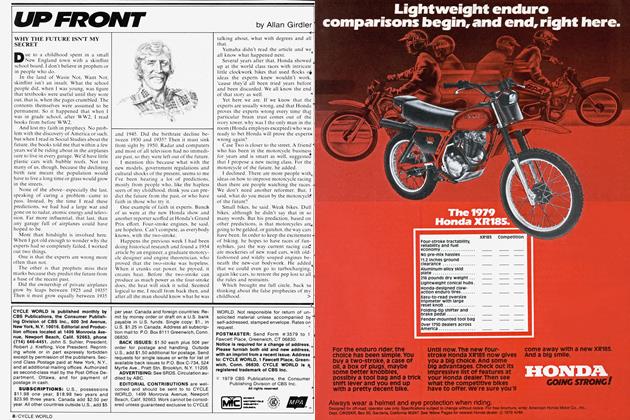

SUZUKI RM400N

CYCLE WORLD TEST

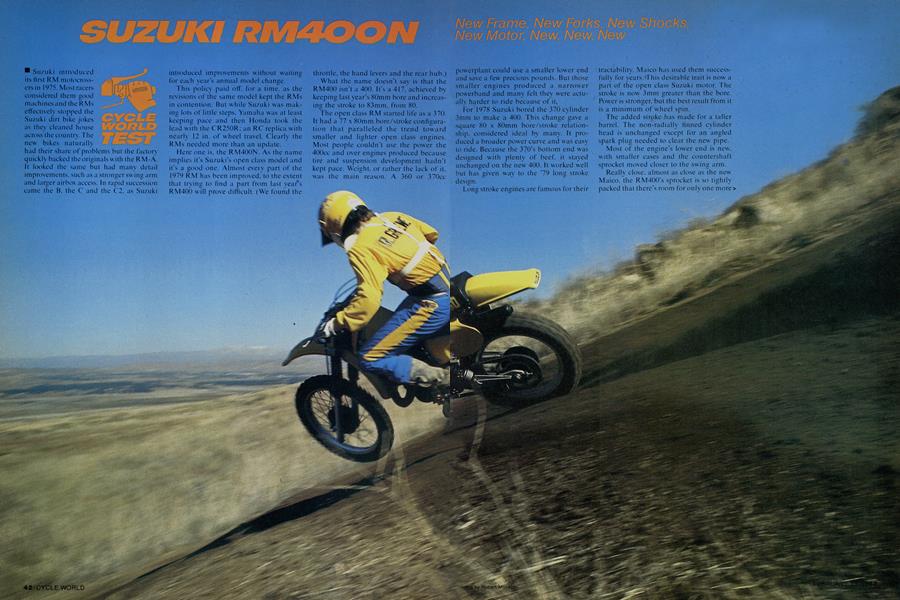

Suzuki introduced its first RM motocrossers in 1975. Most racers considered them good machines and the RMs effectively stopped the Suzuki dirt bike jokes as they cleaned house across the country. The new bikes naturally had their share of problems but the factory quickly backed the originals with the RM-A. It looked the same but had many detail improvements, such as a stronger swing arm and larger airbox access. In rapid succession came the B, the C and the C2, as Suzuki introduced improvements without waiting for each year’s annual model change.

This policy paid off. for a time, as the revisions of the same model kept the R Ms in contention. But w hile Suzuki was making lots of little steps. Yamaha was at least keeping pace and then Honda took the lead with the CR250R: an RC replica with nearly 12 in. of wheel travel. Clearly the RMs needed more than an update.

Here one is. the RM400N. As the name implies it’s Suzuki's open class model and it's a good one. Almost every part of the 1979 RM has been improved, to the extent that trying to find a part from last year’s RM40Ö will prove difficult. (We found the throttle, the hand levers and the rear hub.)

What the name doesn’t say is that the RM400 isn't a 400. It's a 417. achieved by keeping last year's 80mm bore and increasing the stroke to 83mm. from 80.

The open class RM started life as a 370. It had a 77 x 80mm bore/stroke configuration that paralleled the trend toward smaller and lighter open class engines. Most people couldn't use the power the 400cc and over engines produced because tire and suspension development hadn't kept pace. Weight, or rather the lack of it. was the main reason. A 360 or 370cc powerpiant could use a smaller lower end and save a few' precious pounds. But those smaller engines produced a narrower powerband and many felt they were actually harder to ride because of it.

New Frame, New Forks, New Shocks, New Motor, New, New, New

For 1978 Suzuki bored the 370 cylinder 3mm to make a 400. This change gave a square 80 x 80mm bore/stroke relationship. considered ideal by many. It produced a broader power curve and was easy to ride. Because the 370’s bottom end was designed with plenty of beef, it stayed unchanged on the new 400. It worked well but has given way to the ’79 long stroke design.

Long stroke engines are famous for their

traetability. Maico has used them successfully for years. This desirable trait is now' a part of the open class Suzuki motor. The stroke is now 3mm greater than the bore. Power is stronger, but the best result from it is a minimum of wheel spin.

The added stroke has made for a taller barrel. The non-radially finned cylinder head is unchanged except for an angled spark plug needed to clear the new pipe.

Most of the engine’s lower end is new. with smaller cases and the countershaft sprocket moved closer to the swing arm.

Really close, almost as close as the newMaico, the RM400’s sprocket is so tightly packed that there’s room for only one more> tooth. Well, maybe two. No flaw here, though, because not many riders will be brave enough to gear this one for more top end.

The larger engine is a softer engine. There has been no attempt to squeeze maximum power out of it. Instead, the 417 is tuned to. have all the power the tire can transmit at nearly all racing speeds, with a flat torque curve across the band. The carb is a 36mm Mikuni, same as on last year’s smaller 400. Induction is a combination of case reed and piston port used successfully by Suzuki previously. By starting fuel flowing into the crankcase before the piston has opened the regular port and then shutting the door before the mix can escape, the case reed widens the useful powerband.

Part of the new engine is a giant clutch that refused to chatter or slip under hours of racing, but could still be worked by two fingers. The engineers took advantage of the new cases to move the clutch control arm from the cover to the far side of the center case. The old system had the linkage on the cover, which flexed under load. The clutches then dragged and/or the bike crept forward on the starting line. RM racers quickly learned not to snick the thing into gear until just before the gate dropped. The new cases locate the arm and its working parts opposite the clutch, in the center case, with a pushrod between arm and clutch. Flex is gone and the clutch completely disengages when the clutch lever is pulled.

The shift and brake levers have been trouble spots on past RMs, as both tended to work loose and fall off if not checked for tightness often. Now an aluminum forging is used for the shift lever. It is well designed and doesn’t loosen. The pedal end doesn’t have a rubber cover; formed ridges are used instead and do an excellent job. The kickstart lever has had its attachment redesigned. Rather than use a pinch system like before, the lever completely encircles the start shaft and is held in place by a bolt that screws into the start shaft’s center. This should eliminate loose and lost kick levers. Too bad they didn’t copy Yamaha’s non-slip pedal. The RM uses a smooth, slippery device guaranteed to get you the first time you try to start it with wet or muddy boots. Forget about starting it in your garage unless you have boots on. it will surely put a hole in the calf of your leg. A fine powerplant like this deserves a nonslip kickstart pedal.

A new frame holds the potent 417cc engine. It looksjust like the frames DeCoster and Wolsink have been using for the last couple of years. The large steering head, single backbone and downtube look much the same as last year. The rest of the frame tubing is new. Two small tubes split from the downtube and cradle the engine. Two large tubes run from the end of the backbone tube, (about the seat/tank junction) bow out and continue down to butt into the engine cradle tubes. A series of small, straight tubes are welded together to form upper mounts for the shocks, and tie the seat rails into the heavier tubes behind the motor. The whole thing is fabricated from chrome-moly tubing, heavily gusseted, and painted black.

RM footpegs have always afforded a good grip, but due to their construction, soon started to droop. They were built from many thin pieces of metal and the pivot pin would elongate the hole through the peg and let it sag. Suzuki factory bikes have been using a cast iron peg with an excellent fine-tooth top and a broad bearing surface for the pivot. These same pegs are employed on the 1979 RM 400N. Their construction and grip are superior to the old design. In addition, they have the strongest return springs we have ever seen. Forget about mud sticking them in the up position; it won’t happen. There’s no worry about feet being knocked off the pegs in deep mud ruts either. It’s 17 in. from the ground to the top of the peg. The left peg is attached to a short frame tube that runs between the center downtube and the engine cradle. The right peg is mounted to a heavy steel plate that bolts to the same tube on the right side.

There’s a reason for the difference in mounting styles. The countershaft sprocket is on the left which puts more load on the left side of the frame. So a tube is used to strengthen the left side. The right side doesn’t have as much loading, so a flat plate can be used to beef up that side and it allows room for an all-new rear brake pedal to run behind the frame tubes, where it can’t catch on the rider’s boot or be damaged in a fall. It has excellent leverage and uses a rod to operate the same rear brake that came on the first RMs. But don’t judge from past experience; the rod and new lever ratio provide a strong, progressive and controllable brake. Part of this excellence is the direct result of the fine full-floating brake backing plate that pivots on needle bearings. The static arm runs parallel to the swing arm and is the same length.

The RMC-2 had a truly ugly aluminum swing arm. It was made from several aluminum die stamped parts and welded together. For ’79 the RM has the most beautiful extruded aluminum arm made. By using an extrusion, welds have been kept to a minimum and strength to a maximum. Its top gusset is actually part of the extrusion, trimmed to the desired shape. Its bottom appears flat but actually has extended, extruded sides. On the chain side, an extra piece of aluminum has been welded on to prevent chain damage. A giant square tube ties the sides together just in front of the tire and a smaller tube houses the pivot bolt farther forward. Thick plates are used at the rear for axle placement. Workmanship and welding are first class.

Gas-charged, remote reservoir. KYB shocks are mid-mounted on the swing arm and fully cantilevered. They look different than last year’s, and are. The dual springs have been dropped in favor of a single progressive spring. Preload is accomplished by moving a snap ring to one of three grooves on the shock body. Damping can be adjusted by removing the spring and turning the shaft. Only two choices are provided but one of them should suit most any rider. Moving the shocks farther forward has moved the infamous Suzuki bulge (caused by the upper shock mounts) farther forward. It is noticed immediately w hen standing on the pegs. A bow-legged stance is required to clear it. but doesn't bother the operator as much as first impressions indicate. Starting the big RM can be difficult if sour boots are wet. The slippery lever is a Tfif|sance. The kiek lever is well designed except for its slippery end. A choke lever has finally been put back on the Mikuni carburetor and makes it easy to use. Three or four kicks will bring the 400 to life when cold, two or three when warm. Cluteh pull is light and the transmission drops into low without a noise.

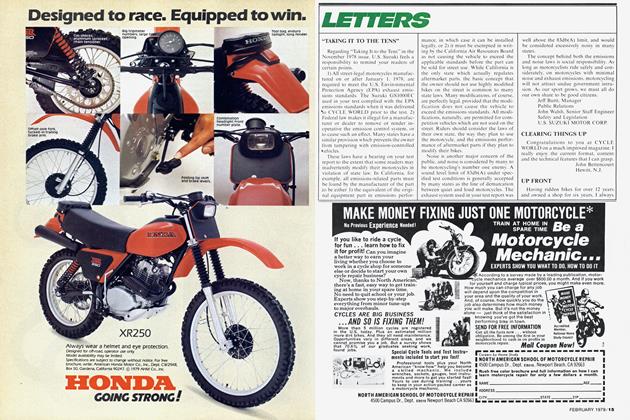

The front forks are completely new for '79. Stanchion tube size has been increased to 38mm. They are leading axle units that utilize air/oil hydraulic internals. Travel is 11.8 in.

A large full-width front hub has replaced last year's smaller conical unit. This larger front brake has been used on factory MXers for several years and is welcome on the big 400. The engine on last year’s bike easily exceeded its brakes. This large hub. combined with the redesigned rear, provide excellent brakes.

Every year the steering rake gets steeper on motocross bikes. This is partly due to the increased suspension travel raising the bike, making turning more difficult. Last year’s RM had 30° of rake angle; the ’79 has 28.5°.

Triple damps are cast aluminum and the top clamp carries backmount, rubberinsulated handlebar pedestals. A flat bend, low rise handlebar is used. It looks too low but feels perfect when riding, forcing the rider to lean forward, a position that works when riding the 400 hard.

The RM is a tall machine. Imagine 13.5 in. of ground clearance, peg height of 17 in., and a seat height of 37.5 in. Several staff members had trouble touching the ground. Once under way everything is fine until it becomes necessary to dab or stop, then the short person will have a problem. Our measurements are taken unladen and change quite a bit when a rider gets on. Like most ultra-long travel bikes, the RM's soft suspension lets the bike sink a couple of inches w hen a rider climbs on.

Hand levers and throttle are just like they’ve been since 1975. The levers aren’t doglegged, but are decent anyway. The throttle is another matter. Its action is fine, but the ê$#(a* thing just isn’t long enough for a large hand. Only three fingers w ill fit if your hand is big. Trying to install aftermarket grips is also a hassle; trying to shrink them to fit the throttle can be frustrating. If Suzuki w'ould add an inch to the grips, they would be fine.

The RM’s styling has also been updated for 1979. It has a Star Wars look that takes a while to get used to. Some of the staff didn’t like the looks of it, others raved about how! neat it was.

Lenders, tank, front number plate and LIM legal side plates, are made from a tough, flexible plastic. The front one is wide, long and effective. The rear is also wide and deep. The factory replica tank holds 2.2 gal. and lets the rider slide up on it easily to load the front wheel in slippery, tight corners. Its filler hole size isn’t as large as a PE’s, but is large enough to see the fuel level w hile filling. A blue stripe on the tank and side number plates add a touch of color. These decals are good thick ones but still will be rubbed off by your knees if contact paper isn’t kept over them.

Even the seat is new-. It’s the same thickness but the shape has changed to a trimmer style. RM400 is boldly printed in yellow' on the sides of the seat cover and adds to the modern image.

The big RM uses aluminum wheel rims made by Tagasago. The front hasn’t changed, but the back one is new. It’s a wide 2.5 in. model with deep center, much like the rims used on Husqvarnas. The deep center makes tire changing much easier and the extra width puts more tire on the ground.

Under way. the suspension that felt almost too soft when stopped is almost perfect; compliance over small objects is right on. and it takes ditches and gullies without bottoming. Sky jumps can be taken as fast as the rider desires. Landings are soft and controlled. The excellent suspension absorbs even the biggest impacts without complaint or adverse reaction.

The shocks are fantastic, as good as anything made. The 38mm forks have equally superb action and don't leak oil. bind or flex.

Shifting is positive and precise but stiff until several miles are traveled. The aluminum lever was raised one notch, but the shaft has a course spline and the lever was then too high. By carefully bending it in a vise, it could be positioned between the splined positions. This position gave a little better leverage and made shifting easier.

The 417 doesn’t feel anything like last year's 400. Vibration is slight, not severe. Power has increased dramatically and most of it is useable, thanks to the long stroke design. Wheelies at any speed, in any gear, are easy. It takes a couple of riding hours to feel completely at ease on the machine. Its high footpeg placement and high forward seating position require a short adjustment time. This rider placement makes body position on the bike important. Too far forward in a corner will let the rear of the bike slide too much, too far back and the front wheel will lift and skate, in between will put the bike and rider through the> corner extremely quickly. It doesn’t matter where the bike is placed in a corner; the low inside line or high in the berm, it goes where it's pointed and holds the intended line. The steep rake makes it a jet when squaring tight corners but causes a little wobbling at high speed in sand. A novice may find the RM400 hard to control. It is an all-out serious motocross racer, and as such demands a rider capable of controling its quickness through corners and sensitivity to rider position.

SUZUKI RM400N

Gearing is perfect; second or third gear can be used for motocross starts, fifth will go faster than most tracks have room for.

Primary starting is still absent so a stall means searching for neutral before restarting.

It’s refreshing to ride an open class Suzuki that has good brakes. Good probably isn't a strong enough word; impeccable describes them better. They are strong, controllable, progressive and don't chatter.

Flex isn’t part of the RM400 package. It is rock solid. Nothing twists, bends or moves around that shouldn't. The beautiful aluminum swing arm. large forks, gas reservoir shocks, and chrome-moly frame are top quality parts.

The RM sounds noisy up close but the

sound doesn't carry far. Normal two-stroke engine clatter and a single wall pipe add noise when close. The silencer is large, and effective.

Many people thought last year’s RM400 was a better playbike than racer. Actually, it was fairly good at both. The 1979 RM400N definitely isn’t a playbike. for anyone but an expert. It is an all out racings machine, capable of competing with factory works bikes and is very close to the bikes Roger D makes his living on. It could do the same for a hot. unattached, local pro. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontWhy the Future Isn't My Secret

February 1979 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1979 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound-Up

February 1979 -

Short Strokes

February 1979 By Tim Barela -

Technical

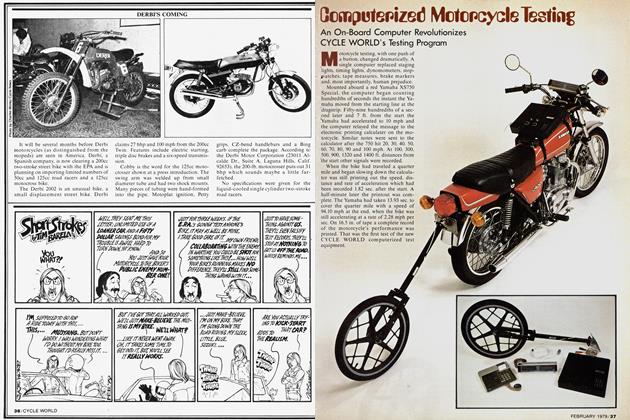

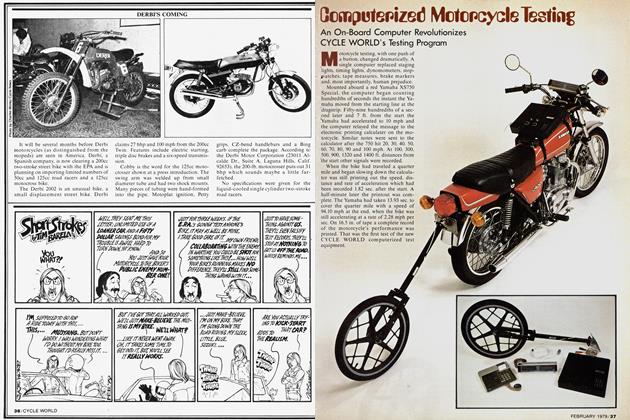

TechnicalComputerized Motorcycle Testing

February 1979 -

Features

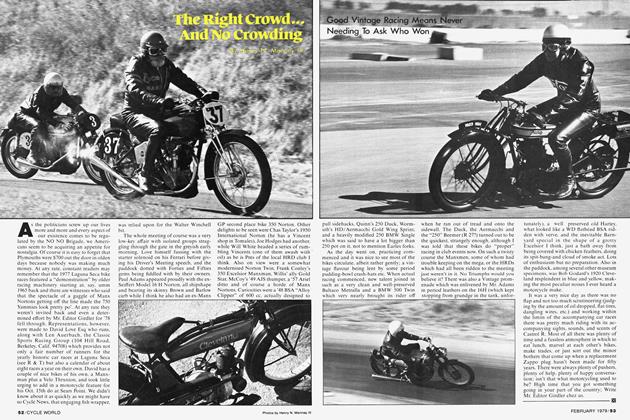

FeaturesThe Right Crowd... And No Crowding

February 1979 By Henry N. Manney III