YAMAHA XV92O

A Big Japanese Sport Bike For The Man Who Doesn't Want A Four

CYCLE WORLD TEST

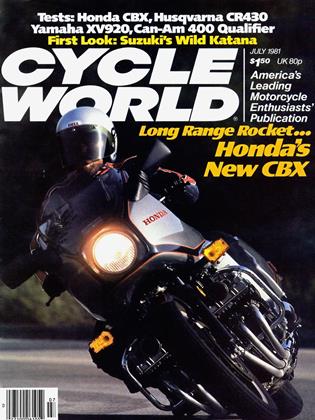

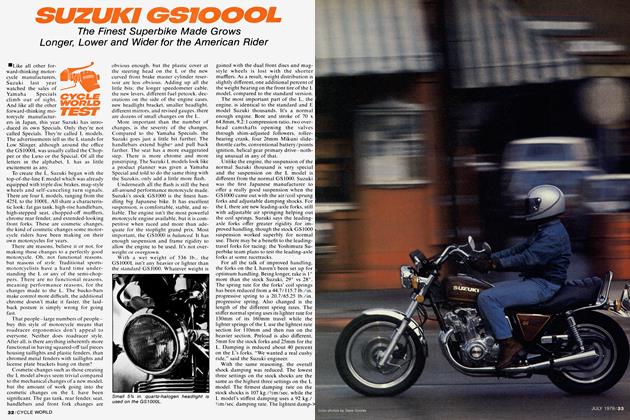

Clothes, our mothers told us, don’t make the man. That’s not always the case with motorcycles. On bikes, the shape of a gas tank or the length of the handlebars or the curve of the seat not only tells the rider what the bike is, but it tells ot-her riders what kind of a rider this is. Which brings us to the Yamaha XV920.

Think of the XV920 as a Yamaha Virago in a jogging suit. Underneath the swoopy sidecovers and the tall gas tank there’s the mechanical core of the Virago. Only the shorter handlebars, the double front disc brakes, the seat crawling like a caterpillar up the back of the gas tank, all say that this is a more athletic machine than the Virago. It’s longer legged with its higher gearing and the chain drive. It’s stronger with its larger pistons and bigger valves.

Yamaha has gone to great lengths to make the XV920 different from the Virago. Yet somehow the similarity comes through. People at gas stations or at meeting spots along winding motorcycling roads would see the XV920 and ask about the Virago. They had heard about the Yamaha V-Twin but weren’t sure about the versions.

The difference between the Virago and the 920 is as wide as the Atlantic Ocean. Yamaha’s American division originally proposed the V-Twin motorcycle and described the features they felt would appeal to American riders. That’s where the Virago began. But to make the project feasible the European Yamaha agents had to have a version, and they wanted a bike with a larger engine and more sporting configuration. That’s where the 920 was founded.

As it turned out, both markets got both bikes, but with a little difference. The Virago, or XV750, remains essentially the same whether it’s sold in Europe or America. But the big version comes with a 920cc engine in America and a 981cc engine in Europe, achieved with even larger pistons.

Whichever version of the bike it is, there are lots of common pieces. All versions use the same built-up backbone frame with a monoshock rear suspension and stressed engine. Most of the engine pieces are the same in all the bikes, although there are three sizes of pistons and two different drivetrains, chain on the 920 and shaft on the Virago.

Like its smaller sibling, the XV920 has a sohc V-Twin engine with the cylinders set at a 75° vee. There’s a single throw crankshaft held in the cylinder cases with roller main bearings and plain bearing two-piece connecting rods. The 69.2mm stroke is the same for all engines, but the crankshaft is balanced differently for the 750 and 920cc engines to compensate for the larger 92mm pistons of the big motor. Bearing sizes on the crankshaft are the same for big and small versions of the> motor, but connecting rods are different. The larger motor uses a shorter 6.1 in. rod while the 750 uses a 6.3 in. long rod. Additionally, the 920 gets a 2mm larger wrist pin for greater strength. Why the shorter length connecting rod on the bigger motor? For one, the longer rod on the smaller motor helps the smaller motor develop more low-end power. Also, the larger pistons of the 920 get more beef above the wrist pin while working in the same height cylinders.

Cylinder height was kept the same so top end components would interchange. And the Yamahas are a marvel of interchangeable parts. Because the silent-type cam chains drive the cams on opposite sides of the engine and the front cylinder has the exhaust in front and the intake at the rear, while the back cylinder is opposite this, the entire top ends of the two cylinders are identical, but twisted 180° on the crankcase. Camshafts in the 920 are the same as those in the 750, although they open bigger valves in the bigger engine. The 750 uses 43mm intake valves and 37mm exhaust valves, while the 920 uses 47mm intake valves and 39mm exhaust valves.

Compression is reduced on the 920 to 8.3:1 from the 8.7:1 of the 750. And if these sound like low figures for a modern Japanese engine, that’s probably all the compression the engine could stand and still run on what passes for gasoline in our lead-free world considering the diameter of the pistons and the relatively mild state of tune of the camshafts.

Like the smaller Yamaha V-Twin, the 920 bristles with novel features to keep the engine running silently and running for a long time. The cam chain drive sprockets have spring-loaded tensioner teeth to keep the cam chains from rattling. And the small cast aluminum covers over the camshaft sprockets have cast-in pins to keep any bolts from backing out just in case.

Cam chain tension is maintained with a slipper on one side of the chain and an automatic plunger-type tensioner on the other side. Because the engine is a stressed member of the frame, there are huge cylinder head bolts holding on the head, plus a large flat mating surface between the head and cylinder. This makes for a very rigid engine, but it also increases heat transfer from the head to the cylinder, assisting engine cooling. To seal the joint a special bore ring is used, rather than a normal head gasket. External oil lines relieve the head-cylinder joint from holding in oil pressure without leaks, a possible problem with a stressed engine.

Much work was done measuring engine temperatures and working on engine cooling so that the rear cylinder operates at the same temperature as the forward cylinder. In addition to the heat transferred through the cylinder, the exhaust passage in the cylinder head is very short and a shrink-fit sleeve holds the exhaust pipe in while dissipating heat to the head. The frame has been designed so there’s an air pressure outlet through the frame for air that’s passed around the rear cylinder. And the pistons receive a special coating to reduce the thermal load, all important when dealing with large diameter pistons.

Feeding the engine a diet of emissionregulated low-lead and polluted air are a pair of linked 40mm Hitachi CV carbs. These are the same on the 920 as they are on the 750, and the actual bore size, typical of CV carbs, is smaller than the nominal size, so that they can be considered 36mm carbs by any normal measurement.

Air is fed to the carburetors through the pressed-steel frame, which ducts the air from the airbox under the seat.

If you’ve been counting, you may have noticed a number of tasks assigned to the strange frame. Various ducts and shrouds on the frame duct air into the carburetors, away from the rear cylinder, while attachments bolt to the engine for support. Additionally, the rear suspension is housed within the backbone. All that and it must securely locate the steering head and swing arm pivot, hold the various little pieces that attach to the frame, not transfer too much engine vibration to the rider, and be relatively simple to produce. That’s a lot of work for a frame, and the Yamaha’s unusual design satisfies these demands excellently.

This frame is also adaptable. Because the 920 uses an enclosed chain drive, while the 750 uses a shaft drive, the frame must be usable with both systems.

That’s where the stressed engine system comes into play. The swing arm doesn’t pivot on the frame, or what we could call the frame. Instead, the swing arm pivots on the back of the engine, which is also part of the frame. Thus when the shaft drive is bolted to the engine, it is adapted to the frame automatically.

Drivetrain differences between the 750 and 920 are limited to the final drive unit. The primary drive ratios, transmission, and clutch are all identical for the big and small versions of the bike. For the 750 there’s a helical gear at the end of the transmission that transfers power to the driveshaft. For the 920 there’s a countershaft sprocket driving a 630 chain. And around the chain is a sealed chain case, filled with grease.

Yamaha’s chain enclosure is a much different design than the simple sheet metal shields that were found on small Japanese bikes a couple of decades ago. This is a sealed assembly on the 920, with an aluminum housing around the countershaft sprocket and around the final drive sprocket. Connecting the two housings are a pair of tubes. The tubes are made of a special rubber compound, designed for long wear because the tubes function as chain guides as well as protecting the chain. The forward end of each tube is a bellows-like flexible end that enables the tube to flex with the chain. Inside the tubes is the lithium grease that lubricates the non-o-ring chain.

Obviously the enclosure will keep the> chain protected from water and dust and dirt, and it will keep the chain lubricant from spraying onto the bike and its riders. But it also quiets the motorcycle by insulating chain noise, and all the mechanical noise that can be reduced enables the machine to produce that much more exhaust noise without breaking the legal sound barriers.

The final drive ratio on the 920 is higher than it is on the 750. The rest of the ratios, primary and gearbox, are the same on both the 750 and 920. This gives the 920 a 3.166:1 final drive ratio while the 750 has a 3.207 final drive ratio. As a result of the gearing, the 920 is spinning at 3762 rpm at 60 mph, while the 750 spins at 4032 rpm at the same speed. And this makes the 920 more like other big Twins. Of course the 920 gearing can be changed, which is not the case with the 750.

As on the 750, suspension can be adjusted. Most of the adjustment is in the rear shock and spring. A dual-rate steel spring wrapped around the rear damper comes with a fixed preload. Adjustment of the rear suspension is handled in two ways. Spring rate and preload are changed by adding air to the rubber bladder of the rear suspension unit. Standard air pressure is 14 psi, the minimum recommended air pressure is 7 psi and maximum pressure is 57 psi. The air valve is located on the righthand side of the bike, beneath the seat, where it’s readily accessible. Immediately beside the air valve is a polished metal knob that can be twisted to adjust the rebound damping rate of the suspension. Six positions are possible at the knob, however the cables that connect the knob to the damper can be repositioned on the damper so that a different six positions are available. A total of 20 damping positions is provided. When the knob is turned, the cables rotate a collar that screws a magnesium rod in and out of an orifice. As the tapered rod is moved out, the size of the opening is enlarged, reducing damping. When it’s screwed in, the opening is reduced, increasing damping. Because the rod is magnesium, it expands and contracts with temperature changes to maintain constant damping regardless of shock fluid temperature.

Because the 920 has a slightly longer swing arm than the Virago, the steel spring is slightly stiffer than the spring on the 750. The overall spring rates are similar, though the secondary rate of the 920’s spring is proportionally greater and provides a greater portion of the bike’s springing than the 750’s spring.

Front suspension adjustment consists of air valves on the fork tubes. There’s no crossover tube, so setting the air pressure can be a tricky task, but then there’s no crossover tube or banjo fittings to leak.

Because the 920 has a longer (60.8 vs 59.6 in.) wheelbase than the Virago, and is designed to be a more sporting machine, the designers speeded up the 920’s steering with steeper rake (28.5 ° to 29.5 ° ) and less trail (4.96 in. against 5.24 in.)

The 920 uses conventional wheel sizes, 19 in. front, 18 in. rear, while the Virago uses a 19 front and stylishly fat 16-incher in back. Tires must work as a combination, so the 920 front tire is a quick steering 3.25 x 19 while the Virago comes with a wider 3.50.

The 920’s wheelbase is about average for a 900cc bike and the Virago is long for its displacement. The Seca 750, for instance, has a 56.9 in. wheelbase. The detail changes, as in wheelbase, rake and trail and tire size, result in the 920 feeling different and more nimble than its stocky little brother despite the shared frame and suspension.

If the mechanical differences between the 750 Virago and the XV920 seem substantial, then the styling differences are even more substantial. The difference begins at the headlight where the 920’s huge 8-in. round headlight catches your attention without looking out of place. It conveys an impression of power and strength, even on a motorcycle that’s noticeably smaller and lighter than the average four cylinder superbike. Then there are the spiral cast wheels on the XV920. The actual curvature of the solid spokes is so slight as to not effect the strength of the wheels, yet they are obviously unusual.

Certainly no part of the XV920 is more unusual than the rear-end styling of the motorcycle. The fender is small and wraps tightly around the rear tire, linked to the swing arm so it can follow the tire up and down. Where the rear fender would normally sprout from behind the seat, there is a short rack, an elongated tool box, the rear lights and a bracket for the license plate. Normally the styling touches on most motorcycles can be explained by references. It has a tall gas tank like a BMW or the seat has a lip at the front like a Moto Guzzi Le Mans. But nothing has a rear end treatment like the 920. And if the comments of everyone who saw the bike are any indication, it may never be seen again.

Besides establishing a character for the bike, the styling of the XV920 positions the rider on the bike. The handlebars are a normal enough 30 in. wide, but have only a small rise and enable the rider to lean forward slightly. The pegs are high for excellent cornering clearance, and mounted much farther aft than the pegs on the Virago, again for a more sporting posture. Between these two ends, the seat is low where the rider sits, providing a short distance from the seat to the pegs. The seat also has very little padding, in order to hold down the seat height. Even with the suspension pumped up to maximum air pressures, the seat is only 31 in. off the ground, and it can be lowered an inch with the suspension adjustments.

As seating positions go, this is not one of the more radical positions. It’s not like a bike with clip-ons and rear sets. Not too many years ago, before the invention of the Special, it would have been considered a normal seating position with slightly higher pegs. What doesn’t work with this bike, though, is the seat. It is just plain hard, hitting various riders in various wrong places. It is stepped enough to restrict movement, without offering added support where it’s needed. The simple addition of more padding would make a world of improvement, but that doesn’t seem to be in vogue these days.

Comfort is otherwise very good on the 920. The suspension is supple, whether the air pressure is set high or low. With a firm damping setting the machine can buck on concrete highways, but a softer damping setting makes a substantial improvement in ride quality. The vibration level is about 5 percent higher than a Cadillac Seville. That’s no more than any four cylinder bike, yet without the high frequency buzzing of any of the Fours. There’s not even the standard low frequency pounding of some other V-Twins. Only the quietest of exhaust beats reminds the rider that there’s an engine moving him down the road. Even after long rides the vibration level isn’t annoying at all. This despite the solid mounted engine and no counter-rotating shafts or other silly contrivances. Just good crankshaft balancing and a good design.

With a couple of exceptions, the 920 is a very easy bike to ride, whether one is riding slowly or fast. The exceptions are the heavy, clunking shifting and low-speed carburetion that isn’t right. The clutch has a vague feel, with a broad engagement and moderate lever pull, but the shifter requires lots of pressure, making shifting a task that requires more conscious intent than it should. You don’t shift the Yamaha much without knowing it.

The carburetion problem may be particularly noticeable because the engine runs so well at all engine speeds. This isn’t an engine that must spin above a certain engine speed. It’s smooth and powerful at idle and at 7000 rpm. So there’s a tendency to shift up into the highest gear. Except, between 2000 and 3000 rpm the engine doesn’t want to hold a steady speed without bucking and coughing, especially when cold. It feels as though it’s running out of gas and sliding the choke lever halfway on reduces the tendency, so it’s probably an indication of excessive leanness at low engine speeds.

When accelerating or at higher engine speeds there’re no carburetion problems. The engine responds to throttle cleanly and strongly. Highway cruising or blasting away from stop signs is easy.

Because the 920 has many of the same intake components as the 750 but with larger displacement, the tuning is relatively more mild. Where the 750 would spin past 7000 rpm without the rider even noticing, the 920 begins to run out of wind near redline. It doesn’t protest mechanically, it just finds less urgency in acceleration and that encourages the rider to shift up.

Big Twins are usually misjudged in performance. Everybody knows Big Twins have lots of torque and low-end power and so it’s assumed that all this low-end power and torque will accelerate a motorcycle quickly in top gear. Such is not generally the case, however. Torque is a function of displacement, while the state of engine tune determines whether that torque is produced at a high engine speed or a low engine speed. Because Twins have bigger pistons and longer strokes than Fours of the same displacement, their maximum engine speed is lower, which also depresses the rpm at which maximum torque is produced. For those reasons, the Yamaha produces its 56.4 lb.-ft. of torque at 5500 rpm. Maximum horsepower is produced at around 6500 rpm. A Honda CB900F, for instance, would produce maximum power > at 9500 rpm and maximum torque at 8000 rpm.

But the Yamaha, with its lower redline, must be geared higher than an equivalent Four for reasonable top speed and engine life.

In the Yamaha’s case, it’s a reasonable compromise. It’s not geared quite as high as a BMW 1000. It’s about the same as a Ducati 900. It’s high enough for relaxed highway cruising, good mileage and longevity, and yet low enough for brisk acceleration in high gear.

Measured by dragstrip performance, the XV920 is a strong big Twin, but a slow 900. With its 13.06 sec. quarter mile and 99.44 mph terminal speed, the Yamaha is very close in performance to a stock 900cc Ducati Darmah or BMW R100. Yet Yamaha’s own 550cc Four is just as quick, and any of the 750cc Fours are much quicker in dragstrip acceleration.

And therein lies the key to a big Twin. More cylinders generally result in more horsepower, displacement being equal. But there are relatively few riders who actually do accelerate as hard as their motorcycles will go for a quarter of a mile, at which time they’re going about 100 mph on a bike like the XV920. And the sensation of a big Twin accelerating produces a thudding sensation of strength, rather than the buzzing of a high-revving multi. The Yamaha XV920 has part of this. It has a fine lunge when the throttle is twisted, and it’s respectably fast for its size and configuration. But the exhaust is quiet and the vibration coming through the bars is so restrained that it almost accelerates too effortlessly.

Where the Yamaha enjoys its greatest strength is where it must be steered. Freeways it tolerates. Around town it copes. At stop light drags it tries. But where a paved road twists and turns enough to make a highway engineer frown and a pavement machine driver protest, the Yamaha XV920 rider finds the bike’s reason for being.

That low, narrow, compact engine provides all the power a tight road requires, while not interfering with the bike’s steering and handling. Even the world’s best handling 600 lb. motorcycle can’t change directions like a lighter bike can. And while the 920 isn’t as light as it might be, the weight is low and concentrated and it flicks from left to right to left easily and securely. On a bigger bike one talks about handling. On the 920 one talks about, steering, because the bike is moved about through effort on the bars, not through gross movements of weight around the saddle.

Cornering clearance on the Yamaha extends as far over as the tires can handle. At maximum angles of lean, when the pegs are scraping and the stands occasionally slap at the bumps in the pavement, the tires will squirm and tactless operation of the throttle can make the rear end slide out.

Throughout such extreme riding the machine is stable and controllable and it maintains that fast pace with minimal effort from the rider. It can be held down in a fast corner without great physical effort, making fast riding more fun than it would be on a larger motorcycle.

Braking power is up to the speed of the motorcycle. In our braking tests the bike would stop from 60 mph in 132 ft. and from 30 mph in 31 ft., both excellent figures. Yamaha uses an adjustable front brake lever that can be set for various rider preferences, though the response of the brakes to lever pressure is not always as positive as it could be. There’s almost an isolation between the brakes and the rider that makes maximum use of the front brake slightly difficult. The large rear drum is fine, providing ample power with good control.

Other parts of the motorcycle are generally competent and unobtrusive. The simple round gauges are as elegant and appropriate on a motorcycle now as they were 20 years ago and we’d like to see more bikes come with such clean instruments. The 4.9 gal. gas tank is ample considering the bike’s excellent gas mileage. Mounting the choke on the handlebar and the ignition and fork lock together at the steering head, although becoming common practice, is nonetheless appreciated. Even touches like the locking hinged gas cap are nicely done and well thought out.

The harshest comments the motorcycle generated were all concerning styling. The scoop-like sidecovers, the rear end treatment, the seat shape and the plastic scoop above the forward cylinder head are all unusual shapes some motorcyclists find hard to accept. And parts like the spiral cast wheels look more appropriate on Yamaha Specials or the Maxims, but don’t fit the more sporting image of the XV920.

But styling aside, the XV920 works. Its handling lives up to expectations, the power is very good for the size of the motorcycle, it’s a joy to ride on a variety of roads and it’s an easy motorcycle with which to live.

As the styling is refined in future models we’ll probably see versions that appeal even more, but for now the XV920 is a delightful bike to ride.

YAMAHA XV920

$3499

ACCELERATION