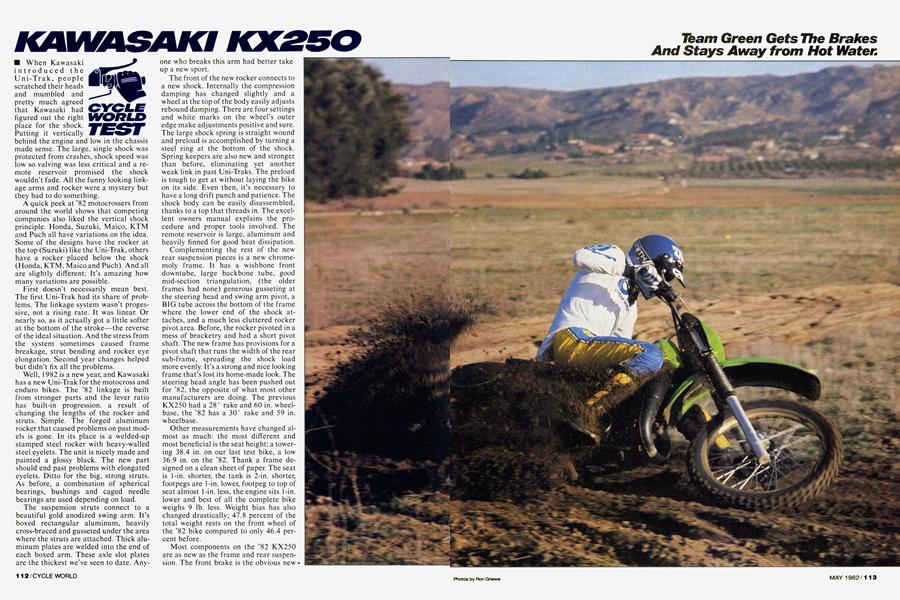

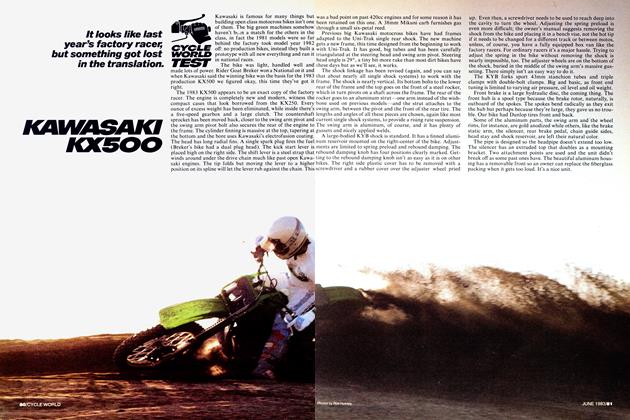

KAWASAKI KX250

CYCLE WORLD TEST

When Kawasaki introduced the Uni-Trak, people scratched their heads and mumbled and pretty much agreed that Kawasaki had figured out the right place for the shock. Putting it vertically behind the engine and low in the chassis made sense. The large, single shock was protected from crashes, shock speed was low so valving was less critical and a remote reservoir promised the shock wouldn't fade. All the funny looking link age arms and rocker were a mystery but they had to do something.

A quick peek at ’82 motocrossers from around the world shows that competing companies also liked the vertical shock principle. Honda, Suzuki, Maico, KTM and Puch all have variations on the idea. Some of the designs have the rocker at the top (Suzuki) like the Uni-Trak, others have a rocker placed below the shock (Honda, KTM, Maico and Puch). And all are slightly different; It’s amazing how many variations are possible.

First doesn’t necessarily mean best. The first Uni-Trak had its share of problems. The linkage system wasn’t progessive, not a rising rate. It was linear. Or nearly so, as it actually got a little softer at the bottom of the stroke—the reverse of the ideal situation. And the stress from the system sometimes caused frame breakage, strut bending and rocker eye elongation. Second year changes helped but didn’t fix all the problems.

Well, 1982 is a new year, and Kawasaki has a new Uni-Trak for the motocross and enduro bikes. The ’82 linkage is built from stronger parts and the lever ratio has built-in progression, a result of changing the lengths of the rocker and struts. Simple. The forged aluminum rocker that caused problems on past models is gone. In its place is a welded-up stamped steel rocker with heavy-walled steel eyelets. The unit is nicely made and painted a glossy black. The new part should end past problems with elongated eyelets. Ditto for the big, strong struts. As before, a combination of spherical bearings, bushings and caged needle bearings are used depending on load.

The suspension struts connect to a beautiful gold anodized swing arm. It’s boxed rectangular aluminum, heavily cross-braced and gusseted under the area where the struts are attached. Thick aluminum plates are welded into the end of each boxed arm. These axle slot plates are the thickest we’ve seen to date. Any-

one who breaks this arm had better take up a new sport.

The front of the new rocker connects to a new shock. Internally the compression damping has changed slightly and a wheel at the top of the body easily adjusts rebound damping. There are four settings and white marks on the wheel’s outer edge make adjustments positive and sure. The large shock spring is straight wound and preload is accomplished by turning a steel ring at the bottom of the shock. Spring keepers are also new and stronger than before, eliminating yet another weak link in past Uni-Traks. The preload is tough to get at without laying the bike on its side. Even then, it’s necessary to have a long drift punch and patience. The shock body can be easily disassembled, thanks to a top that threads in. The excellent owners manual explains the procedure and proper tools involved. The remote reservoir is large, aluminum and heavily finned for good heat dissipation.

Complementing the rest of the new rear suspension pieces is a new chromemoly frame. It has a wishbone front downtube, large backbone tube, good mid-section triangulation, (the older frames had none) generous gusseting at the steering head and swing arm pivot, a BIG tube across the bottom of the frame where the lower end of the shock attaches, and a much less cluttered rocker pivot area. Before, the rocker pivoted in a mess of bracketry and had a short pivot shaft. The new frame has provisions for a pivot shaft that runs the width of the rear sub-frame, spreading the shock load more evenly. It’s a strong and nice looking frame that’s lost its home-made look. The steering head angle has been pushed out for ’82, the opposite of what most other manufacturers are doing. The previous KX250 had a 28° rake and 60 in. wheelbase, the ’82 has a 30° rake and 59 in. wheelbase.

Other measurements have changed almost as much: the most different and most beneficial is the seat height; a towering 38.4 in. on our last test bike, a low 36.9 in. on the ’82. Thank a frame designed on a clean sheet of paper. The seat is 1-in. shorter, the tank is 2-in. shorter, footpegs are 1-in. lower, footpeg to top of seat almost 1-in. less, the engine sits 1-in. lower and best of all the complete bike weighs 9 lb. less. Weight bias has also changed drastically; 47.8 percent of the total weight rests on the front wheel of the ’82 bike compared to only 46.4 percent before.

Most components on the ’82 KX250 are as new as the frame and rear suspension. The front brake is the obvious new

wrinkle. Disc brakes are nothing new for street bikes or flat track racers. On a production motocrosser, it’s new. The steel disc is thin and light and works. A small hydraulic reservoir is built into the hand lever bracket and a high quality braided steel line arcs across the front number plate on its way to the fork leg mounted slave cylinder. The disc bolts to a slick looking spool-type front hub. Spokes don’t loosen or break and they lace to new aluminum rims that are supposed to be twice as strong as last year’s rim.

KYB forks with 43mm stanchion tubes make the front suspension as strong as the rear. Travel is 11.8 in. The lower legs look like those used on most of the ’82 motocrossers from Japan, an aluminum tube instead of a casting and the axle boss is forged then attached to the tube. The bottom of the tube has a welded on cap and the drain screw is also located on the bottom. Normal adjustments are available; oil weights, oil volume and air pressure. Triple clamps have double pinch clamps and the handlebar pedestals are rear-set.

Although the engine looks a little smaller than last year’s, nothing really jumps out and says new. But it is. Still five speeds, the ratios are exactly the same as before—no complaint here. The cases are trimmer. The cylinder is a replica of those

used by the factory racers last year. It may be the most radical part of the bike. When you look down the barrel from either end, all you see is ports.

First and largest is the exhaust, which is both bridged—so a ring won’t snag— and tapered, with the top wider than the bottom. Next to the main exhaust port are two boost ports. Yes, the exhaust, something really rare. The small, square boosters are the same height as the main exhaust port and are just above the transfer ports. On the other side there’s a bridged intake port. The reed cage cavity feeds main intake and boost ports to the crankcase.

The major problem with most designs like this has been eliminated. Usually the cylinder will be light alloy with an iron or steel liner and only the professional racers can spend the time and money to match the ports in the barrel with those in the liner. But Kawasaki’s Electrofusion coating for the bore means there is no liner and thus no need for elaborate alignment work. (It also means the cylinder can’t be rebored, but that’s another problem.)

Naturally a reed valve is used, and it’s more than adequately sized. The whole lower back of the cylinder is reed cavity, filled with an eight-petal cage that has graphite-reinforced plastic reeds. A 38mm Mikuni carburetor makes sure enough gas reaches the giant cavity. And like past Mikunis on Kawasaki dirt bikes,

slot-head main jets are used. Of course they function as well as hex-head main jets, but they are very difficult to find. Mikuni’s used on other makes normally have hex-head jets and that’s what most dealers stock. (We have had trouble finding slot-head jets for Kawasakis. Many Kawasaki dealers don’t stock them).

Other engine internals are a mix of old and new. The clutch is large and strong, the primary gears are straight-cut, all gears are lightened where possible, and the shift mechanism uses a ratchet and pawl in the end of the shift drum. Ignition is a small external flywheel CDI. Most other 250 motocrossers have internal rotor flywheels, Kawasaki’s external unit is just as light and the extra diameter adds to the engine’s smooth and usable power delivery. Also adding to the good power delivery are full-circle flywheel weights in place of the chopped ones used on past KX motocrossers.

The rear wheel assembly is probably the least changed part on the ’82 KX. It’s the same compact but strong hub used before. Spokes are large enough, the aluminum rim is a wide model, the 5.1 in. brake drum has cooling and strengthening fins. The brake arm is in front of the axle where it’s protected and lightening holes are in every piece they could think of.

Air cleaner boxes always pose a problem on single shock bikes. Kawasaki has taken another stab at designing one to fit

around the shock. But it’s nothing to write home about. The small filter is flat with shallow sides. It does seal well and double wing nuts keep it from bouncing around. And the air box has air openings in a protected area under the seat and large oval holes on the top part of the side cover. Getting to the small filter for cleaning, something you may have to do between motos, requires removal of the left side plastic decoration and then three screws in the filter box cover. It doesn’t

take as long as it sounds but it could be easier and simpler.

Other plastic parts are better. The tank is short and the weight rides low on the bike. When tight turns demand weight on the front wheel it’s easy to slide forward on the narrow seat. The long and wide front fender does a good job of protecting the rider. The rear fender includes number plates and the side view is nice and tidy.

The view leaves an odd first impression.

though, because the rear fender looks too high. The explanation is simple. The engineers wanted to lower seat height so they made the seat shorter and tucked it in the valley between tank and fender. Same thickness, and it’s 1.5-in. lower than last year’s.

Most of the bits and pieces that make living with a bike more pleasant are well thought out and won’t require replacement. The shift lever is the only exception. It winds around under the chain and doesn’t have a folding tip. Bad news if the lever gets dragged in a bermed turn. Replace it with one that folds and you’ll save money on transmission parts. Footpegs have agressive tops, strong return springs and open bottoms. The stamped steel rear brake pedal is small, light and has a claw top. A steel rod operates the rear brake and a flat plate keeps the rider’s heel from accidently putting pressure on the rod. Pedal height is adjusted by an easily reached 6mm screw on the rear of the pedal. Hand levers are the popular dog-leg shape and the throttle cable exits parallel to the bars. The throttle even has a protective rubber guard that keeps mud out of the working parts. Grips are good. They are a waffle pattern and about the right hardness for most riders. Handlebars are the right bend and width and won’t require replacement. A kick stand is bolted to the frame, nice to have when the bike isn’t being raced, and easily removed when it is. Chain rub blocks and pads are quality parts, hold up well and don’t make unnecessary noise. The rear chain guide can be adjusted fore and aft and its rear part extends well back under the rear sprocket. Even the tires, Bridgestone’s excellent M22 and M23, work well on most surfaces.

The bike even starts easily. One or two kicks, hot or cold. And because it doesn't have watercoolihg, there’s no need for a 5 min. warm up. Blip the throttle for a half >

minute or so and ride away. Low gear is tall as a motocross gear box should be and the rest of the ratios are perfectly matched to the power output. Acceleration is smooth, predictable and rapid. There’s no bogging, no flat spots and no pipiness. Power is strong and the powerband is very wide for a 250 race engine. The shift lever is quite a distance from the footpeg and tucked in close to the engine, which contributes to boots slipping off the tip until the rider adapts by turning his foot in slightly. Shifting was a little notchy at first but soon loosened up. Shifting under power requires turning the throttle off slightly or a quick touch on the clutch lever. Clutch lever force is near nothing; a four-year old kid could pull it with one finger. When pulled, the clutch doesn’t drag or chatter and it releases smoothly. Not too suddenly, not too slowly.

Straight-line stability is great, the bike doesn’t hop around or try to get sideways. Large bumps and whoops simply disappear. We couldn’t get the bike to go fast enough to be scary across large bumps. Just arrow-straight control and great rider confidence. Compliance on smaller bumps wasn’t as good; the bike doesn’t react easily to them and bounces the rider around. We backed off the spring preload but the straight-wound spring doesn’t like small bumps. Kawasaki then delivered a progressive-wound spring that comes stock on their KX125. It went right on and provides better compliance on chatter bumps. Riders who weigh less than 140 lb. should consider the 125’s spring. Hard riders who weigh more than 140 lb. will probably like the stock spring fine. Most riding was done with the rebound damping adjuster in the second position.

The massive forks worked fine on all parts of the motocross course until someone came off a jump with the front wheel a little too high. Then they exhibited harshness and hydraulic lock. It only happened when the front wheel was slapped down. Lowering the oil level an ounce got rid of most of the problem but then the front end dove when braking hard. In went a batch of 10 and 5 weight, half and half. That cured the complaints and made the fork action on normal ground even better.

Cornering is fantastic. Any place or any part of a corner is the hot spot on a KX250. The bike is totally neutral, it’ll go where the rider wants with no muscle or fight. Riding the berm is equally easy. The KX stays anyplace on the berm with ease. Even bumpy turns are no problem. The strong frame and swing arm give a flex-free, no twist feel.

Braking power was disappointing until we seated the front disc. After a couple outings with marginal to poor front brake power, the bike was taken to a desolate section of pavement and ridden hard for a couple of miles. After being heated and

KAWASAKI

KX250

$2079

cooled a few times, the brake started working well. It has really predictable and linear braking. The more muscle used the stronger and quicker the stop. There is no grabbiness or chatter or violence. It won’t put you over the bars if

you panic and grab a handful of brake. The harder you pull, the quicker the bike stops. It does take a while to get used to the amount of muscle required though. The leverage is more like that required on European motocross machines.

The ’82 KX250 is easier to ride than any 250 motocrosser we’ve tried for a long time. The superb engine power means the rider isn’t constantly trying to out-guess the engine and doesn’t have to shift as if there was no tomorrow. If the engine drops below the optimim power range a slight touch on the clutch lever will put it back in the strong power band. And the light overall weight of the bike, (it’s 1 5 lb. lighter than Yamaha’s new waterpumper 250) makes long motos a breeze. Normal mortals don’t have to worry about the lack of watercooling either. Sub pro level riders won’t be able to ride the KX hard enough or long enough to notice a drop in power from heat build up.

If it sounds like we liked the new KX250, you're reading the test right. We’ve decided to keep the bike in our garage for a long-range test. Its easy starting, quality components, excellent handling and cornering traits, powerful engine and light weight have sold us. 88