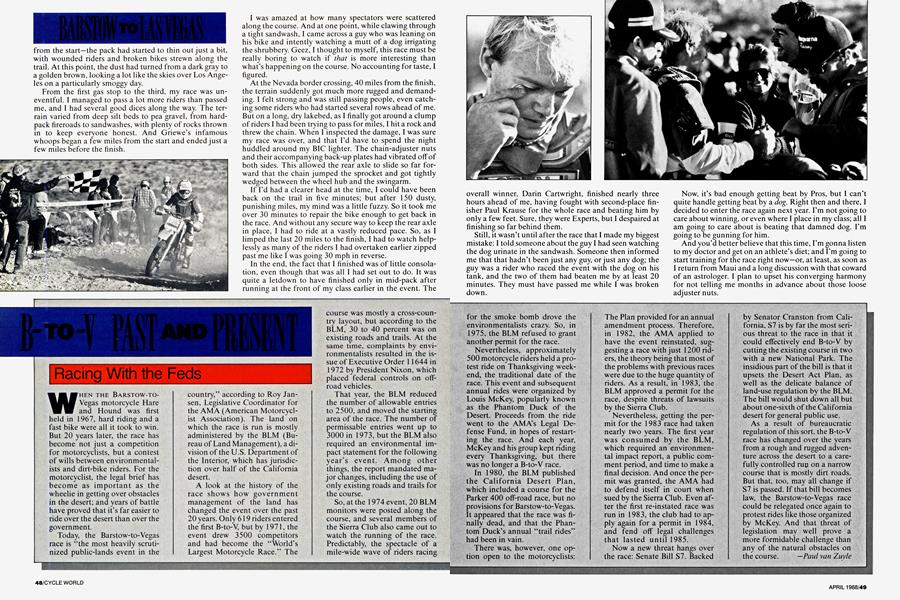

B-TO-V PAST AND PRESENT

Racing With the Feds

WHEN THE BARSTOW-TOVegas motorcycle Hare and Hound was first held in 1967, hard riding and a fast bike were all it took to win. But 20 years later, the race has become not just a competition for motorcyclists, but a contest of wills between environmentalists and dirt-bike riders. For the motorcyclist, the legal brief has become as important as the wheelie in getting over obstacles in the desert; and years of battle have proved that it’s far easier to ride over the desert than over the government.

Today, the Barstow-to-Vegas race is “the most heavily scrutinized public-lands event in the country,” according to Roy Jansen, Legislative Coordinator for the AMA (American Motorcyclist Association). The land on which the race is run is mostly administered by the BLM (Bureau of Land Management), a division of the U.S. Department of the Interior, which has jurisdiction over half of the California desert.

A look at the history of the race shows how government management of the land has changed the event over the past 20 years. Only 619 riders entered the first B-to-V, but by 1971, the event drew 3500 competitors and had become the “World’s Largest Motorcycle Race.” The course was mostly a cross-country layout, but according to the BLM, 30 to 40 percent was on existing roads and trails. At the same time, complaints by environmentalists resulted in the issue of Executive Order 11644 in 1972 by President Nixon, which placed federal controls on offroad vehicles.

That year, the BLM reduced the number of allowable entries to 2500, and moved the starting area of the race. The number of permissable entries went up to 3000 in 1973, but the BLM also required an environmental impact statement for the following year’s event. Among other things, the report mandated major changes, including the use of only existing roads and trails for the course.

So, at the 1974 event, 20 BLM monitors were posted along the course, and several members of the Sierra Club also came out to watch the running of the race. Predictably, the spectacle of a mile-wide wave of riders racing for the smoke bomb drove the environmentalists crazy. So, in 1975, the BLM refused to grant another permit for the race.

Nevertheless, approximately 500 motorcycle riders held a protest ride on Thanksgiving weekend, the traditional date of the race. This event and subsequent annual rides were organized by Louis McKey, popularly known as the Phantom Duck of the Desert. Proceeds from the ride went to the AMA’s Legal Defense Fund, in hopes of restarting the race. And each year, McKey and his group kept riding every Thanksgiving, but there was no longer a B-to-V race.

In 1980, the BLM published the California Desert Plan, which included a course for the Parker 400 off-road race, but no provisions for Barstow-to-Vegas. It appeared that the race was finally dead, and that the Phantom Duck’s annual “trail rides’’ had been in vain.

There was, however, one option open to the motorcyclists: The Plan provided for an annual amendment process. Therefore, in 1982, the AMA applied to have the event reinstated, suggesting a race with just 1200 riders, the theory being that most of the problems with previous races were due to the huge quantity of riders. As a result, in 1983, the BLM approved a permit for the race, despite threats of lawsuits by the Sierra Club.

Nevertheless, getting the permit for the 1983 race had taken nearly two years. The first year was consumed by the BLM, which required an environmental impact report, a public comment period, and time to make a final decision. And once the permit was granted, the AMA had to defend itself in court when sued by the Sierra Club. Even after the first re-instated race was run in 1983, the club had to apply again for a permit in 1984, and fend off legal challenges that lasted until 1985.

Now a new threat hangs over the race: Senate Bill S7. Backed by Senator Cranston from California, S7 is by far the most serious threat to the race in that it could effectively end B-to-V by cutting the existing course in two with a new National Park. The insidious part of the bill is that it upsets the Desert Act Plan, as well as the delicate balance of land-use regulation by the BLM. The bill would shut down all but about one-sixth of the California desert for general public use.

As a result of bureaucratic regulation of this sort, the B-to-V race has changed over the years from a rough and rugged adventure across the desert to a carefully controlled rup on a narrow course that is mostly dirt roads. But that, too, may all change if S7 is passed. If that bill becomes law, the Barstow-to-Vegas race could be relegated once again to protest rides like those organized by McKey. And that threat of legislation may well prove a more formidable challenge than any of the natural obstacles on the course. -Paul van Zuyle

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

April 1988 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

April 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Departments

DepartmentsLeanings

April 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupYen And the Art of Motorcycle Marketing

April 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

April 1988 By Kengo Yagawa