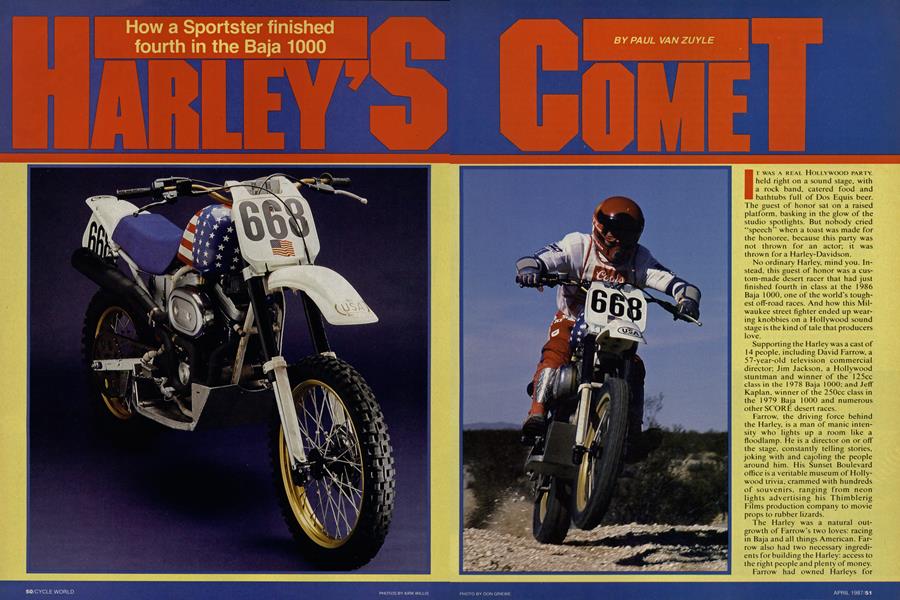

HARLEY'S COMET

How a Sportster finished fourth in the Baja 1000

PAUL VAN ZUYLE

IT WAS A REAL HOLLYWOOD PARTY.

held right on a sound stage, with a rock band, catered food and bathtubs full of Dos Equis beer. The guest of honor sat on a raised platform, basking in the glow of the studio spotlights. But nobody cried “speech" when a toast was made for the honoree, because this party was not thrown for an actor; it was thrown for a Harley-Davidson.

No ordinary Harley, mind you. Instead, this guest of honor was a custom-made desert racer that had just finished fourth in class at the 1986 Baja 1000. one of the world’s toughest off-road races. And how this Milwaukee street fighter ended up wearing knobbies on a Hollywood sound stage is the kind of tale that producers love.

Supporting the Harley was a cast of 14 people, including David Farrow, a 57-year-old television commercial director; Jim Jackson, a Hollywood stuntman and winner of the 125cc class in the 1978 Baja 1000; and Jeff Kaplan, winner of the 250cc class in the 1979 Baja 1000 and numerous other SCORE desert races.

Farrow, the driving force behind the Harley, is a man of manic intensity who lights up a room like a floodlamp. He is a director on or off the stage, constantly telling stories, joking with and cajoling the people around him. His Sunset Boulevard office is a veritable museum of Hollywood trivia, crammed with hundreds of souvenirs, ranging from neon lights advertising his Thimblerig Films production company to movie props to rubber lizards.

The Harley was a natural outgrowth of Farrow’s two loves: racing in Baja and all things American. Farrow also had two necessary ingredients for building the Harley: access to the right people and plenty of money. Farrow had owned Harleys for nearly 40 years, and had only recently sold his 1947 Panhead. Jackson, on the other hand, had never ridden a Harley until two years ago, when he rode a Sportster in Kodak’s award-winning television commercial. He took that bike down a dirt road while no one has looking and thought, “Wow, this is really neat. I have to get one.”

The idea for building the Baja Harley came about in March of 1986 as a joke between Farrow and Jackson, who were swapping stories about racing on the barren Mexican peninsula south of California. Farrow laughed and said, “Hell, we could do it on our Harleys.” Realizing that between the two of them they really could, the pair set out to build what would become known as Harley’s Comet.

The first step they took was to buy a 1986 1100 Sportster and remove the engine. They considered using the 883 Sportster engine, but the additional 217cc of the larger motor came at the cost of just three pounds; and later, in Baja, they would find they needed all the power of the 100. They had originally tried to order just an engine from Harley, but the dealer said that doing so was difficult and would take time. With only six months before the race, time was already at a premium.

Asked why he didn’t choose a racing Harley motor such as the XR750, Farrow said, “Our premise was to take a streetbike and make it to La Paz in pretty good time.”

Next, Jackson called Jeff Cole at C&J racing frames and told him what he had in mind. Jackson remembers hearing everyone in the frame shop laughing along with Cole as he placed the order. But after everyone was done laughing, C&J went to work on wrapping a modified single-shock flat-track frame around the motor.

While the engine was being mated to the frame, Jackson started planning for the race. Knowing the havoc Baja could wreak on spokes, and fearful of the tire wear that the bike’s weight and power would cause, he made up 10 sets of wheels. One set to run on, and nine to be distributed at pit stops along the course. The rims were fitted with the largest Metzeler knobby tires available.

After two months, the chassis was finished, and Jackson mounted a custom-made White Brothers shock at the back and a White Power upsidedown fork in the front. He now had a rolling chassis, but the bike was hardly ready to race.

All the frustrating details of putting a custom bike together had yet to be completed. Since the Harley air cleaner stuck out near the top of the engine, it was impossible to use a large aftermarket fuel tank. So Jackson had Jack Hageman of Morgan Hill, California, fabricate an aluminum tank. They chose to keep the Harley filter because they felt it a perfect system for the desert. “It has a nice, huge, foam air filter, it’s easily accessible and it’s not too wide,” says Jackson.

Bassani Manufacturing bent the serpentine exhaust system, which is tucked against the engine. Although the pipe looks like a leg-scorcher, the riders didn't complain. “The only thing you notice is a little heat on your right thigh,” says Farrow.

Then there were the little things, like cables. They had to be custommade to connect the Magura controls with the Harley carb and clutch. The bike also had to be completely rewired, eliminating the instruments, turnsignals and taillight. Jackson then added two 100-watt Cibie headlights mounted in a Pacific Racing bracket. He retained the stock electric starter, since it wasn’t possible to get a kickstarter for the Sportster engine.

Jackson had built the bike in his spare time, continuing to work in the studios while the project was underway. Finally, just three weeks before the race, at 2:30 in the morning, Jackson and co-rider Kaplan hit the starter button. “We had to fight each other to see who would ride it first,” remembers Jackson. “I hopped on and rode it up the street and thought, ‘Okay, where are all the things that are wrong?’ It felt like a perfectly normal motorcycle. I went through the gears and was shocked at how powerful it was. I came back and told Kaplan to take it for a spin. When he came back, he just exclaimed, ‘Gawd.’ ” Later, Kaplan said, “When I first saw it, I thought, ‘Oh, man, this thing is gonna kill me.’ But the more I rode it, the better it felt.”

Grabbing another bike, they took off for the hills in the middle of the night and rode for hours. “The lights were incredible,” Jackson recalls.

In the weeks they had left, the pair put about 200 test miles on the Harley. The battery cracked from vibration, so Jackson arranged to have batteries strewn along the race course in case they were to fail regularly. The carburetor also broke, but to combat that he just prayed.

After the addition of a fabricated skidplate that looked like the bottom of a Sherman tank, the bike was ready for Baja. But Farrow, with his busy directing schedule, had only one chance to ride the bike for a few minutes before going to Mexico—and he was the one who would start the race. Needless to say, his confidence wasn’t at an all-time high.

“We named the bike Harley’s Comet because we thought that, like Halley’s Comet, the bike wouldn’t make it through the race.” And there were other skeptics in Baja, evidenced by the laughter that ensued when the bike was rolled out in Ensenada, the race’s starting point. Dan Ashcraft, who was riding one of the two factory Husqvarnas, advised, “You’ll turn that rear tire into a dishrag in 20 miles.” Ashcraft, it turned out, didn’t finish the race.

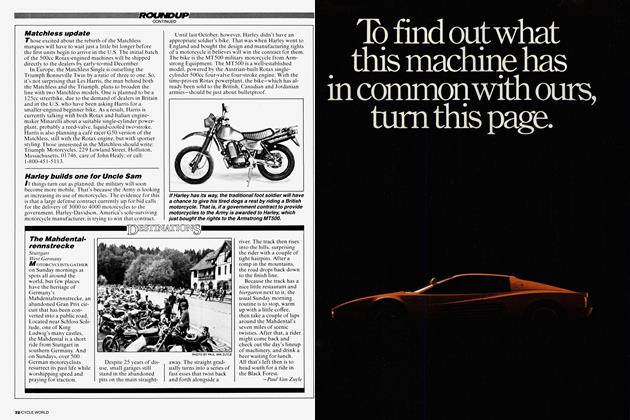

At the starting line, Farrow lined up with a rider on a BMW Paris-Dakar replica, who took one look at the Harley and sneered in disgust. When their starting minute came up, Farrow took off and never saw the BMW again. The German bike failed to make it to the first check.

Farrow rode without incident to Santa Maria, 230 miles from the start. He was met there by Jackson, who gave the bike a thorough goingover. Amazingly, the rear tire still looked new and the drive chain had barely stretched.

Farrow, who five years ago had driven the entire race by himself in a car, also felt fine. So Jackson put him back on the bike, and drove down the highway to meet him again at Santa Ines, 120 miles down the course. “I pulled into one pit and the guy who came over was about my age. He looked into my helmet and said, ‘Jesus Christ, how old are you?’ I said, Tm 57,’ and he cheered me on,” says Farrow, smiling.

But after 75 more miles of riding though rocks, Farrow began to get tired. When he arrived after dark in Santa Ines, he had ridden for 12 hours, averaging just over 25 mph. Now it was time for Jim Jackson and Jeff Kaplan, whose ages combined are less than Farrow’s, to try to match the 55-mph average of the race leaders.

Jackson nearly did it, charging throughout the night and passing all kinds of bikes and cars until he ran into trouble in the silt beds near El Arco. There, the Harley’s 440 pounds had its way with Jackson, and he crashed three times. The last time was the worst, and when he got up, the bike was badly bent and the light bar had broken off. It took him 45 minutes to repair the bike, and he remounted the light bar with two hose clamps he had put in his toolkit as an afterthought just before the race.

Unfortunately, the hose clamps didn’t hold and the light bar fell off again, the wires shorting against the fork tubes. Jackson grabbed the lights with his left hand, put the bike in first gear and trudged his way to the next pit. Kaplan, too, had problems with the lights during his stint at night and ended up carrying the lights for over 50 miles.

Kaplan also got a scare when he hit a bump while riding flat-out on one of the road sections. When the rear suspension bottomed, the tire grabbed the parts bag that was tied to the rear fender. The bag locked the rear wheel, and Kaplan skidded off the road. When he pulled the bag away from the swingarm, it was empty.

The rest of the race was relatively uneventful, and the spares that had been lost were never needed. Harley’s Comet finished the Baja 1000 in 30 hours, 49 minutes, good enough for fourth place in Class 22 (for Open bikes). In La Paz, the bike looked in remarkably good shape, with only the broken rear fender and a small trickle of oil from the front cylinder head as evidence of its 1000-mile journey.

The odds against the converted Sportster actually finishing the race were astronomical. “A lot of guys say, ‘Let’s build a motorcycle,’ but they just talk about it. To really finish and make it work, that’s a miracle,” says Farrow.

But miracles don’t come cheap. At first, the team figured the effort would cost about twice the $5500 price tag of the stock Sportster. But just making up the 10 sets of wheels ate up much of that budget. The final cost of the bike added up to more than $19,000. And the total output for the race, including the Hollywood party, was nearly $32,000.

Farrow and company have no firm plans to race the bike again. Harley’s Comet will go on display first at a local dealer, then hopefully in Milwaukee. After the race, Farrow, ever the patriot, said, “Î think America needs to do more of this, and I think Harley-Davidson is great because they’ve said, ‘We are not going to quit.’ They should have quit 15 years ago. I admire their courage to stay in business. We could build a machine like the Husqvarna in America if we wanted to, but we obviously don’t want to. What Jim Jackson and I are saying is that if we wanted to build a competitive racer, we could. We wanted to put people on notice. Entering the bike in the Paris-Dakar Rally would prove it, but we can’t afford it. Based on what Baja cost, Paris-Dakar has to cost at least $300,000. Maybe Malcolm Forbes will give us the money.”

Jackson, too, is proud of his creation. “I honestly think that in the hands of Bruce Ogilvie and Chuck Miller (overall 1986 Baja winners), the bike could win Baja, or something like the Parker 400. It would be capable of taking the overall.”

Jackson also knows there is still room for improvement, especially in reducing the bike’s weight. He speculates that 40 pounds could come off without hurting reliability. But he is also thinking about something he calls the Baja Sport, a dual-purpose Harley-Davidson à la the BMW R80 G/S. “It would be a stock 883 or 1100 Sportster with subtle changes, like a little more suspension travel at each end. I bet it could be made to sell for $6000.”

A crazy idea? Certainly no crazier than riding a Harley-Davidson in the Baja 1000. S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe Best of Rides, the Worst of Bikes

April 1987 By Paul Dean -

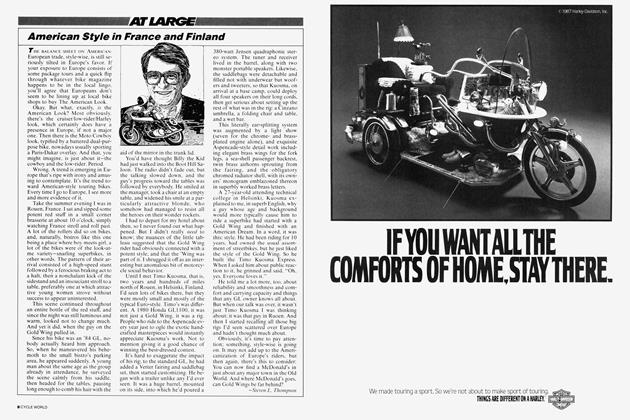

At Large

At LargeAmerican Style In France And Finland

April 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1987 -

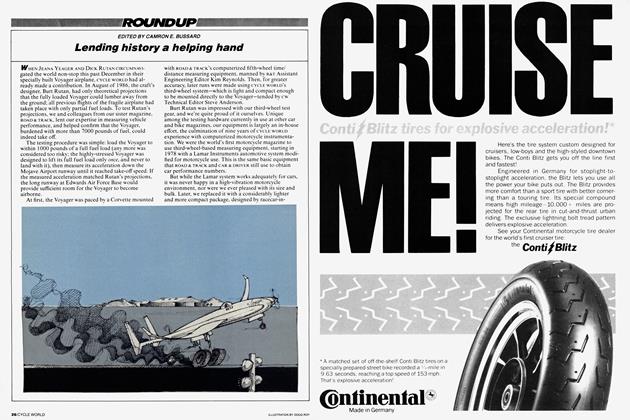

Roundup

RoundupLending History A Helping Hand

April 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

April 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

April 1987 By Alan Cathcart