Adios, specialization

EDITORIAL

AS THE YOUNG MAN STARED AT THE glistening new motorcycle, a Honda Hawk GT, he seemed genuinely bewildered. “It really looks great,” he said, “but what’s it supposed to do?”

With that question, I suddenly became the confused one. What did he think it was supposed to do, make coffee? It’s a motorcycle; it’s supposed to be ridden. But, since I’m a proponent of the belief that no question asked in earnest is stupid, I stifled my inclination to issue a sarcastic response.

“I’m sorry, but I don’t quite understand what you mean,” I replied.

“Well, just look at it,” he said. “It has an aluminum frame, a one-leg swingarm like on some racing bikes, and kind of a hunched-over riding position. So, it seems like it ought to be some sort of sportbike. But there’s no fairing and just one front disc brake, and the engine is a V-Twin instead of a Four. It looks trick, but I wouldn’t buy one, because I don’t know what it’s supposed to do.”

This incident occurred earlier this year, before any tests of the Hawk GT had hit the newsstands, which explains why the kid had never before seen or heard of the bike. But his comments still caught me off-guard. He seemed pretty articulate for his age, which was about 19 or 20, so I figured he wasn’t brain-damaged. And judging by his bike (600 Ninja with Dunlop Sport Elites and a Kerker pipe), his riding gear (Shoei Z100 helmet, Hein Gericke jacket, Bates boots, Dainese gloves) and the way in which I had met him (chasing along a remote backroad at a reasonably spirited pace), he was no stranger to motorcycles. He later even told me that he occasionally reads motorcycle magazines, including this one. Yet, he couldn’t figure out where a Hawk GT fits into the picture.

I thought about all of this for a while before the obvious hit me: Of course the kid didn’t know what the Hawk was “supposed to do”; we have taught him to think in a way that doesn’t allow him to understand a bike like that. And by “we,” I mean virtually every aspect of the motorcycle industry.

It began about 15 or 20 years ago, when each of the large manufacturers realized that a good way to increase market share would be to sell models designed specifically for one particular riding purpose or another. The advertising agencies then created campaigns for these machines that heralded the coming of the age of specialization. The dealers soon got the message and started matching motorcycle specialties with those of prospective buyers. The motorcycle magazines joined in by praising specialized models for raising the standards of performance so far and so quickly. Even the aftermarket people jumped on the bandwagon by building accessories that made specialized models even more specialized.

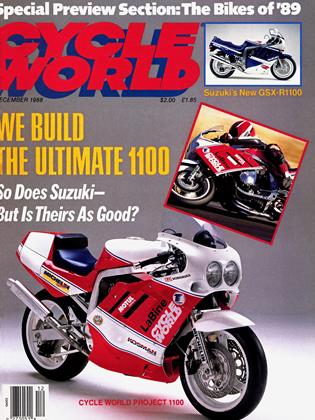

This practice was so successful that it continued, growing and evolving until motorcycling became, for all intents and purposes, nothing but specialization. In the Sixties, a manufacturer might have offered 10 or 12 different models; by the late Seventies, that same manufacturer was offering 10 or 12 different types of models. New-bike lineups soon contained machinery purpose-built for every imaginable use—touring bikes, sport-touring bikes, roadrace-replica sportbikes, all-around sportbikes, VTwin cruisers, power cruisers, dualpurpose bikes, motocross bikes, enduro bikes, playbikes, desert bikes, cross-country bikes.

Thankfully, the industry stopped just short of absurd specialization; we never quite reached the point of designing bikes specifically for moonlight rides on alternate Tuesdays by left-handed vacuum-cleaner salesmen who lisp. But the general-pur-

pose, all-around motorcycle—the machine that had been the mainstay of the industry since the very beginning-got lost in the shuffle. And along the way, we created a whole generation of riders who have difficulty understanding bikes that don’t have a specialized purpose in lifebikes such as the Hawk GT. As a result, many of them simply ignore these models when they make a newbike purchase.

This, along with the minimalist promotional campaigns that have accompanied most all-purpose bikes over the last decade, explains why such machines have not met with much sales success of late. But that’s beginning to change. The market is still dominated by specialized motorcycles, but more models offering a wider range of uses are starting to appear. Even some specialized sportbikes—Honda’s Hurricane 600 and Kawasaki’s Ninja range are good examples—have been designed to perform adequately in other environments. The biggest remaining challenge, then, would seem to be in reeducating the current generation of riders to appreciate the virtues of versatile, all-purpose motorcycles.

This is a good thing, particularly in these days of suppressed sales and shortages of entry-level riders. It’s tough enough to draw new people into the sport as it is; but when you force them to become specialists before they even have time to figure out where the brake pedal is located, you end up chasing more away than you bring in. There still is—and always will be—room for highly specialized bikes; but they should be the exception, not the rule.

After all, the purpose of a motorcycle is not to meet a narrow set of performance requirements, but to fulfill the wants and needs and dreams of its rider. That, in fact, is the message I left with the kid on the Ninja before we parted company. As he stood there watching me climb aboard the Hawk, I asked, “Okay, so you don’t know what this bike is supposed to do; but do you like it?”

“Yeah,” he replied.

“Well,” I said as I started the engine and snicked the transmission into gear, “that’s all any motorcycle is supposed to do.”Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

At Large

At LargeEngineers

December 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Learnings

LearningsThe Buck-A-Day, 25-Year Habit

December 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupWhither the Passenger?

December 1988 By Steve Anderson -

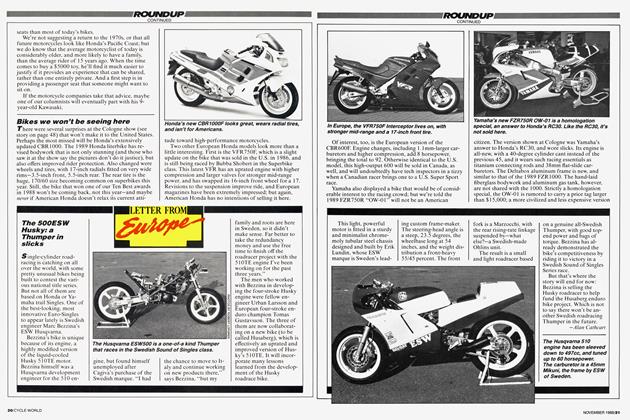

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

December 1988 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupDestinations

December 1988 By Steve Anderson