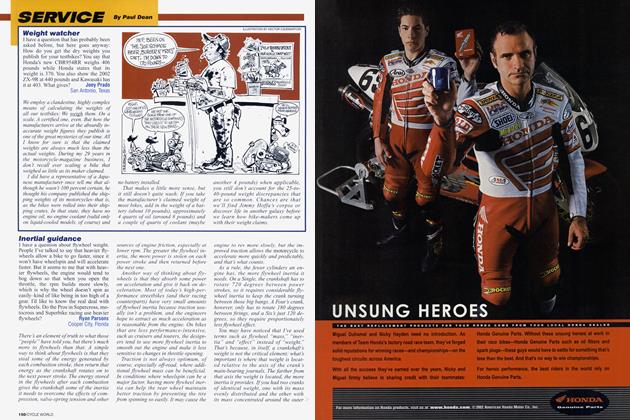

SERVICE

Paul Dean

Sex, lies and blueprints

I frequently read or hear people talking about having an engine “blueprinted.” What does that mean, and how does it affect an engine’s performance? I asked my boyfriend, but the only thing I learned from his answer was that he doesn’t know, either. Diane Lisanti Parsippany, New Jersey

Blueprinting is the process by which every significant part of an engine is carefully measured and then recalibrated or corrected to meet an exact set of predetermined specifications. For production vehicles, those specifications usually come from the engine designer’s blueprints, thus the term. In the case of racing or hopped-up motors, that data might not necessarily be in blueprint form but instead in specifications determined by aftermarket engine builders or companies that develop high-performance equipment.

Every component in a mass-produced engine is not absolutely identical to every other component carrying the same part number; although those parts are manufactured to close tolerances, not all are exactly the same. And most of the parts in any given production engine are randomly selected as the bike is assembled at the factory. So, the performance of that engine is dependent upon how its particular combination of tolerances stacks up. If say, the deck height

of an engine’s cylinders is on the high side of the permissible tolerance range, and the length of the connecting rods just happens to be on the short side, that engine is likely to have a marginally lower compression ratio than one with a low deck height and long connecting rods. There also are countless other ways in which an engine built with randomly chosen components can perform slightly better or slightly worse than other examples of the same engine.

This is why the top teams-especially

the factory-backed ones-involved in production-bike racing blueprint their engines; they want to optimize performance while still staying within the rules. They end up with an engine that outperforms any non-blueprinted version of that same model, yet still is considered “stock” because all of its specifications fall within the manufacturer ’s prescribed tolerances.

So, I have to ask: What else is your boyfriend telling you that you can’t believe?

The need for speeds

I recently purchased a Honda RC51, which has a six-speed transmission, and my previous bike was a Yamaha V-Max, which was only a five-speed. My problem is that when I’m doing 55 to 60 mph on the RC51, the engine is weak-feeling, like it is not running in the proper rpm range. When I drop down to fifth, however, it feels fine. Will prolonged running in fifth gear hurt the transmission? And will changing one of the sprockets reduce the sixth-gear problem? Larry Langley Posted on America Online

Your bike doesn’t have a “problem.” What you describe is typical behavior for a motorcycle of the RC51 s ilk compared with something like the V-Max. The Yamaha is a non-competition-oriented power cruiser with an 1198cc V-Four engine that pumps out about 115 horsepower at 8500 rpm and 82 foot-pounds of torque at 6250. It’s tuned to deliver strong midrange performance over a very wide powerband, and its overall gearing allows it to reach a top speed of slightly under 150 mph. The RC51

is a 999cc V-Twin racer-replica that, despite its 199cc-smaller engine, makes 10 more horsepower-125 at 10,100 rpm-but only 72 foot-pounds of torque at 8000. It is tunedfor optimum power in the upper onethird of the rpm range, and it’s gearedfor a top speed of more than 170 mph.

Therein lie the differences in roll-on acceleration. With Mr. Max, 55 to 60 mph in top gear is right in the fat part of its wide, flat torque curve, which accounts for its superb top-gear acceleration at those speeds. But not only does the 199cc-smaller RC51 make less peak torque than the V-Max, at 55 or 60 mph it is spinning well below its torque peak. So, by comparison, its roll-on acceleration feels weak.

By contemporary sportbike standards, however, the RC51 is a pretty decent midrange performer. The problem is, if you ’ll pardon the cliché, that you can’t have your cake and eat it, too. V-Twins inherently crank out better lowand middle-rpm torque than four-cylinder engines of similar displacement, but when their peak horsepower is boosted to com-

petitive racing levels, much of that torque advantage is lost. Plus, for a motorcycle to be capable of 170-mph-plus speeds, it must have relatively tall gearing in top gear; and tall gearing, combined with a higher-rpm powerband, compromises top-gear roll-on performance.

Both of your suggested remedies are perfectly acceptable, if not entirely rational. Cruising the highways in fifth gear rather than sixth would not harm the transmission in the least. And lowering the final gearing with a larger rear sprocket or a smaller front-or both-indeed would enhance top-gear acceleration. In either case, fuel mileage will be adversely affected and the engine will be buzzier at road speed, but if you don’t care about that, you ’re home-free.

Of course, you could take the logical route and simply downshift when you want quicker acceleration. After all, that’s why motorcycles have shift levers.

Float follies

The carburetor floats on my Suzuki 600 Katana overflow gasoline, and I can’t un-

derstand why. I’ve installed new genuine Suzuki needles and seats, but the carbs still overflow. If I raise the floats by hand, the fuel stops flowing, but all four carbs overflow once the float bowls are in place. The floats do not have holes in them, and they are set to Suzuki’s specs. I have fixed this type of problem many times in the last 45 years, but not this time.

David Maness

Posted on America Online

Sounds like the floats are improperly adjusted, despite your insistence to the contrary. Your own test procedure, in which you push the floats upward by hand, demonstrates that if the floats are raised far enough, the needles and seats will successfully shut off the flow of fuel. You claim that the floats have been adjusted to “Suzuki s specs,” but you didn’t mention where those specs came from-a shop manual, verbal instructions from a local dealer, etc. Someone may have given you wrong information, or perhaps you misunderstood the adjustment instructions. If you don’t already have a shop manual for your Katana, you should buy or borrow one and meticulously follow the float-adjustment procedure it describes.

The only other possible cause of the

FEEDBACK LOOP

In the April, 2002, issue, you informed a gentleman about a device that allows recalibration of electronic speedometers (“Yellow speedo thingo”). Well, another way to resolve the problem of an incorrect speedometer-whether electronic or mechanical-is to buy a used Garmin GPS III (not the III Plus model; it’s too expensive) receiver from eBay and attach it to your handlebars with a RAM GPS mount. For under $150, you’ll have, among other things, a speedometer accurate to .1-mph, a moving map so you won't ever get lost, and a maximum-speed indicator so the police will know precisely how fast you were going when you sliced that deer in half. You can power it from your bike's battery and easily move it from one bike to another. Just don't get so absorbed in the GPS that you forget to look ahead (see above deer reference). Allan Levene

Augusta, Georgia

Thanks for reminding me of that option, Allan. I have a Garmin receiver that I use all the time, even when riding off-road. Indeed, a GPS /////// Plus can provide a lot more information than the three functions you describe. It’s a trip timer, a trip odometer, calculates average trip speed, informs you of that day ’s time of sunrise and sunset, and displays your current latitude, longitude and altitude. It’s also a calendar, a compass and an extremely accurate clock. It even can keep track of where you travel and then use that exact path to guide you back to your starting point-an enormously useful feature for off-road exploration. But it ’s not quite as easy to move from bike to bike as you indicate. All of the available GPS mounts I’ve ever seen are designed to attach either to the crossbar or to one side of a dirtbike-style handlebar; if you have any other kind of handlebar, especially a sportbike with short, clip-on type bars, you’ll have to get creative to fashion a mount that attaches elsewhere. And the mount you make for one such bike might not necessarily fit another. Nevertheless, a GPS receiver is a worthwhile investment, even if your speedometer is dead-nuts accurate.

overflow problem is that the floats have somehow gotten bent or misaligned enough to hang up on the float bowls when the bowls are installed. The chances of the very same misalignment having occurred on all four floats, however, are somewhere between slim and none.

Failing the acid test

Earlier this year, I had a problem with the charging system on my 1997 Honda CBR900RR, which caused the battery to boil over and spill acid all over the swingarm. I had the problem fixed and replaced the battery, but the stains are still on the swingarm. I tried using Brasso and some other metal cleaners, but nothing seemed to work. I even tried 600-grit sandpaper, but that also did nothing. I then thought I could polish the stains out, which meant doing the whole swingarm, but the areas that had been attacked by the acid would not come clean. My only remaining option seems to be to replace the swingarm. Got any other advice?

Frank Mrozowski

Cortland, New York

What you are dealing with are not “stains ” in the usual sense of the word; the sulphuric acid from the battery has eaten into the surface of the swingarm and actually dissolved some of the aluminum. I don’t know how deeply the acid has etched the material, so I can’t be certain whether or not the marks can be removed altogether. Your best bet is to take the bike to a professional metal-polishing specialist and ask his expert opinion. If he doesn’t think the marks can be completely buffed out, you ’ll either have to replace the swingarm, paint or powdercoat it a complementary color, or simply live with the blemishes.

Taming of the screw

I recently replaced the stock exhaust on my 2001 Kawasaki ZRXl 200R with a full Muzzy Ti system and installed a Factory Pro 2.5 jet kit in the carbs, then had the bike dynoed to see the results. I set the idle mixture screws at 2XU turns out as recommended by Factory, but the exhaust-gas analysis from the dyno runs show that the engine is running lean, especially at lower rpm. I’m pretty sure that to correct this leanness, I need to change the idle mixture screw settings, and here’s where the confusion lies. I and my friends (we are not pros but we do have some mechanical knowledge and did all of the mods ourselves) think that to riehen the mixture, I should turn the screws in; but both the tuning guide included with the jet kit and my local bike

mechanic say I should turn the screws out to riehen the mixture. I thought that turning the screws out would let more air in and thus make the already-lean mixture even leaner. Any advice would be greatly appreciated. Theo Merian

Bloomington, Illinois

The instruction sheet and your mechanic both are correct: The pilot screws on your Kawasaki’s carburetors should be turned out (counterclockwise) to riehen the idle mixture. Why? Because they adjust fuel, not air. Many earlier carburetors were just the opposite, with screws that adjusted the amount of air in the mixture affecting the idle and the throttle

response just off of idle. But on most modern carbs, the pilot screws adjust the amount of fuel in that mixture. That method of adjustment results in better fuel atomization for more stable idling and enhanced throttle response, and also helps reduce emissions.

Determining whether the adjusting screw on any conventional motorcycle carb regulates fuel or air is a dead-simple process. If the screw is located at the very front of the carb, it adjusts fuel; if it is located at the very rear of the carb, it adjusts air. That only makes sense, since the best place to adjust air is close to the point where it enters the carb, and the most logical place to adjust fuel is right before the mixture enters the intake tract. And in all cases, turning the screw inward decreases whatever it is adjusting and turning the screw outward increases it.

Different strokes

Now that GP bikes are switching to fourstroke engines, could you please shed some light on this question: Why are engine-braking forces so much greater on an inline four-stroke engine than on a two-stroke or a Vee configuration?

Dave Califano Posted on www.cycleworld.com

There’s an excellent question clunking around in there, though it has gotten somewhat lost in your oranges-and-apples comparison. Whether an engine has an inline or Vee configuration is largely irrelevant when it comes to the degree of braking it provides on trailing throttle. Instead, engine braking centers mainly around 1) whether the engine is a two-stroke or a four-stroke; 2) the number of cylinders; and 3) the amount of flywheel inertia.

Inherently, a four-stroke provides more engine braking than a two-stroke

of comparable displacement and cylinder count. For one thing, a four-stroke has to overcome the friction of its valve gear; every time the cam lobes push the valves open against the resistance of the valve springs, a lot of friction is created that doesn’t exist in a twostroke. The more valves an engine has, the greater that resistance, and the faster the engine is spinning, the more often that resistance occurs.

What’s more, a four-stroke offers more compression resistance than a twostroke. For all intents and purposes, the compression cycle on a four-stroke lasts one full stroke of the piston, starting at Bottom Dead Center and continuing up to Top Dead Center. But in a two-stroke, the effective compression cycle only takes place during approximately the last half of the piston ’s upward stroke; the first half is used to push spent gases out the exhaust port. That’s why you often see the compression ratio of a twostroke listed in two forms: theoretical (which is measured just like a fourstroke ’s by dividing the cylinder volume at BDC by the volume at TDC) and effective (which measures the cylinder volume at the very point where the piston just closes the exhaust port and divides it by the volume at TDC ).

Flywheel inertia also plays a large role in engine braking. Engines with a lot of flywheel inertia provide less braking, because energy stored in the flywheels (which was “stolen ” during acceleration) is released on deceleration. Harley-Davidson Big Twins are perfect examples: Although big, long-stroke, V-Twin engines, these H-D motors decelerate rather lazily because of their huge, heavy flywheels. A Suzuki GSX-R1000 Four, on the other hand, which has very little flywheel inertia, slows very rapidly when the throttle is closed. □

Got a mechanical or technical problem with your beloved ride? Can’t seem to find reasonable solutions in your area? Maybe we can help. If you think we can, either: 1) Mail your inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663; 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631-0651; 3) e-mail it to CW1Dean@aol.com, or 4) log onto www.cycleworld.com and click on the Feedback button. Please, always include your name, city and state of residence. Don’t write a 10page essay, but do include enough information about the problem to permit a rational diagnosis. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of inquiries we receive, we can’t guarantee a reply to every question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue